THE anti-corruption rhetoric has been the flavour of the last several seasons with a political party morphing out of it and briefly capturing power in Delhi in the winter of 2013. The party chief-cum-ex-Chief Minister even came out with the ‘rogue’s gallery’ of the most-corrupt politicians, who actually run India’s democracy-turned-kleptocracy. Incidentally, all of them have come to occupy positions of power and influence through the electoral process.

The ‘Kejriwal List’ had several ‘big fish’ in it. Subsequently, he went ahead and filed an FIR against a much bigger corporate shark. The question is: are these named-and-shamed high-level kleptocrats on the run, now that the Lokpal Act has been enacted? Far from it. Because, the legislation that has come out of the ‘India Against Corruption’ (IAC) movement, with lots of theatrics in full media glare, is more of a farce. It stands testimony to India’s immense propensity for jugaad and dramatises things that achieve nothing.

Lokpal, as contemplated now, is unwieldy and top-heavy and its focus has been heavily diluted by including millions of Class III and Class IV government employees within its ambit though action on their corruption would be the responsibility of the Central Vigilance Commissioner (CVC). Ironically, the Kejriwal-driven Delhi Jan Lokpal Bill, that failed to materialise, is also in the same league—covering all public servants from the Chief Minister to Group D employees, making it as unfocused as the Central Act. This serious aberration would protect the corrupt ‘big fish’ and end up chasing petty bribe-takers. In the event, Lokpal would be damp squib while providing hundreds of well-paid sinecures and draining out huge public funds.

Even if Lokpal becomes functional, it will only be a top-end, not an end-to-end solution. India’s governance structure has two kinds of leadership—political and administrative. While the latter, comprising of the All India Services and State Civil Services, have defined rules and norms for entry, the former, comprising politicians, have none. Anyone with money and muscle power can get a ticket and become an MLA or MP and Minister by openly bribing and inducing voters by adopting dubious means. These ‘leaders’ then loot to their heart’s content and all that citizens can do is to petition the high-and-mighty Ombudsman. Since most of Lokpal would comprise of former judges, the procedure is bound to be cumbersome and the wait would be long and endless.

The best way is to stop these corrupt bandicoots is at the threshold. The bottom-end solution would prevent corrupt and criminal elements from contesting elections, and if they manage to get a ticket and enter the fray, defeat them. This is possible only if the electoral contest takes place on a level-playing field and voting is done with ethics, and not cash, as the principal consideration.

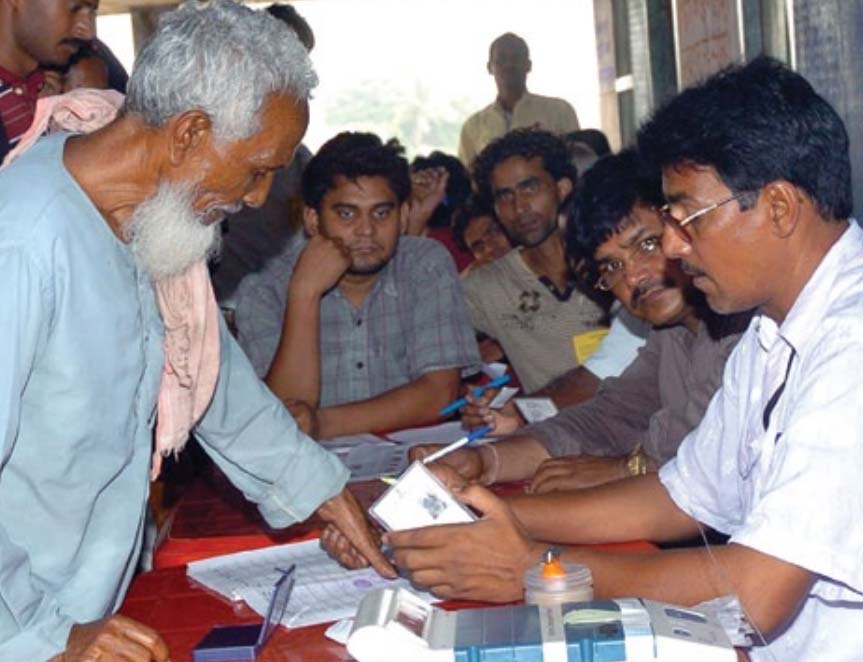

It is here that electoral integrity comes in. Integrity is described as “uncompromising adherence to moral and ethical principles; soundness of moral character; honesty”. If there is one area where this is badly absent in India, it is in the electoral process through which political leaders are elected to govern the country. It is true that the country’s track record of timely elections has drawn universal admiration, particularly because in most other post-colonial countries, elections have been a major casualty. This has given considerable prestige to the Election Commission of India (EC) and legitimacy to India’s democratic polity and its politicians, who are the beneficiaries.

But the moot point is what kind of ‘leaders’ get elected? Many of them do not have basic leadership qualities and are mere henchmen or sycophants of dynastic/party chieftains. Nearly a third of elected representatives face serious criminal charges such as murder, rape, abduction and offences relating to moral turpitude. Almost all of them have amassed wealth much beyond their known sources of income. They have no concern for honest governance or ecological sustainability.

Absence of ethics in voting and a skewed electoral playing field—tilting it heavily in the favour of the criminal and the corrupt—has prevented honest, committed and competent youth from entering the electoral contest. Hence, there is an acute leadership crisis which is resulting in the diminishing of democracy and decay of democratic governance. This is India’s biggest challenge.

THERE are three ways in which integrity could be brought into the electoral process:

Political Reforms: This would involve major efforts to bring inner-party democracy, transparent functioning and merit-based selection of candidates, free of criminal and corruption taint. This is in the hands of political parties, who do not even want to be recognised as ‘public authorities’. No go as of now!

Electoral Reforms: As the government is controlled by these very political parties, it is averse to reforms. Proposals from EC are pending for several years. No go again!

Electoral Integrity Initiative: This requires the electorate to be in action to make EC stringently enforce its constitutional mandates, existing laws and judicial pronouncements to effectively combat corruption and criminalisation in the electoral process. This is in the hands of civil society, of course with the co-operation of EC. This is the best option.

This option was put into practice by the Forum for Electoral Integrity (FEI), in the form of an intense campaign during the 14th Tamil Nadu Legislative Assembly election held in April 2011. The EC was fully involved and SY Quraishi, the then Chief Election Commissioner (CEC), led from the front. As a result, electoral corruption was put on a leash. So much so, that the widely held public comment was: “Earlier, the EC just announced the elections. Only now they are conducting it.” Civil society, spearheaded by the FEI, played a key facilitating role in this.

The backdrop to the campaign was institutionalisation of electoral corruption through cash, freebies and liquor during the bye-election to Thirumangalam Assembly constituency (January 2009). The EC then was less effective and there was no civil society force to counter this venality. In the event, the ‘Thirumangalam Formula’ of cash-for-votes evolved and was touted as the sure-shot way of winning the 2011 State Assembly election.

The bottom-end solution would prevent corrupt and criminal elements from contesting elections, and if they manage to get ticket and enter the fray, defeat them. This is possible only if the electoral contest takes place on a level playing field and the voting is done with ethics, and not cash, as the principal consideration

Open brandishing of this ‘terror of money-power’ demoralised the voters with most of them losing hope for fair elections. Besides, being a frontal onslaught on democracy, this was an affront to the dignity and self-respect of voters, who were being treated as purchasable commodities. This had to be countered and combated. Only people’s power, in general, and youth power in particular, backed by a proactive EC, could do this. For this, civil society had to assert itself and voters had to be educated and mobilised. The EC had to be sensitised about the realities on the ground and persuaded to enforce stringent electoral discipline with the legal and plenary powers it already had, instead of endlessly waiting for long-term electoral reforms and change of heart of political parties.

THUS, the FEI was formed as a civil society coalition in August 2010. The Forum addressed and interacted with several thousand students in their campuses, with full participation of the management and staff. These interactions brought out the appalling disconnect between the ‘first generation voters’ and the electoral process. There was a general perception among college students that they were not relevant to democracy and vice-versa.

This, perhaps, was the worst failure of governance in India and the most dangerous challenge to the country’s democracy itself. In response, the electoral integrity campaign sent out clear and categorical messages that election is the foundation of freedom and democracy and vote is the most basic of all democratic rights; those who offer bribes for vote are making voters a ‘partner in loot and corruption’; once a voter sells the vote, he/she cannot demand any other right or services like safety, shelter, water, sanitation, healthcare, education, etc.; and, selling one’s vote is like selling one’s honour, self-respect and dignity and for the youth, it is bartering their very future. These forceful messages had their impact.

Commencing from the day of announcement of elections—March 1, 2011—the EC swung into action with the police and income tax observers searching and seizing millions of rupees (the final total was Rs. 620 million) being moved for bribing the voters. Senior civil and police officials, who were suspected to be aiding and abetting the movement of cash were summarily transferred. Through a well-knit communication network using SMS, the Forum facilitated the steps taken by the EC team. The impact and enormity of these seizures was seen from the CEC’s statement later: “For every million rupees seized, the EC had possibly prevented 50 to 60 million rupees being given as bribes!”

Information on these developments spread across the State and voters gradually regained confidence in the fairness of the poll. This resulted in a much higher voter turnout—78.12 per cent compared to 70.70 per cent in 2006. The ‘additional’ 8 per cent voters, comprising of youth, urban middle class and senior citizens, had been influenced by the Forum’s campaign and voted in anger. The result was that the money/muscle power did not win the election.

The electoral integrity campaign in Tamil Nadu sent out clear and categorical messages that the vote is the most basic of all democraticrights; those who offer bribes for vote are making voters a ‘partner in loot and corruption’

The CEC confirmed this with a text message sent to the FEI convener: “Thanks a lot for leading the civil society campaign against corruption. I consider our victory against money in Tamil Nadu more important than success in West Bengal.” Gopalakrishna Gandhi, the former Governor of West Bengal, who is settled in Chennai, endorsed this in an email: “The emphatic result in TN is a mercy. Anything else would have been flaunted as the public’s unconcern with corruption… What a wonderful performance by the Election Commission! Congratulations to you for catalysing so much by way of free and fair polls.”

Newton’s Third Law—‘every action has an equal and opposite reaction’—did work with the EC and people jointly pushing back corruption and money power in elections, thereby restoring the integrity and dignity of election and democracy. One strong message came out of this Tamil Nadu experience—in conducting ‘free-and-fair’ polls, if the EC and civil society come together, wonders can be achieved.

Based on this faith, the EC has now evolved a formal partnership with civil society through the ‘Framework of Engagement’. The goal of the ECI-CSO Partnership is “to have every eligible citizen on the electoral roll and have every enrolled voter to vote voluntarily, thus ensuring widest electoral participation and inclusive elections through information, education, motivation and facilitation to promote informed, ethical voting.”

In the run-up to the forthcoming Parliamentary elections, the electorate has some new tools to bring about integrity in the elections and choice of candidates. These include the use of NOTA option to dissuade political parties from fielding criminal and corrupt candidates. They can go for large-scale usage of NOTA as ‘Right to Refuse’ and take it further as an effective instrument of ‘Right to Reject’, moving towards cancellation and fresh election with fresh candidates if NOTA scores the highest votes in a constituency.

THE CIC order, bringing political parties under the RTI Act, should also be aggressively used for seeking information from political parties on funding as well as criteria adopted for selecting candidates to contest elections. Also taking advantage of the Supreme Court’s observation—“Freebies shake the root of free and fair elections to a large degree” —the electorate should mobilise against this corrupt indulgence. Voters must also realise that taking bribes to vote is a criminal offence punishable with one year imprisonment.

Much needs to be done to transform the electoral integrity campaign into a full-fledged movement to make India corruption-free. This is a task cut out for civil society. This is what IAC should have done instead of fracturing into a political party, forming minority government in Delhi and making a mockery of governance. Indeed unfortunate!

The article is an adapted version of the paper presented by the author at the ‘Conference on Technology, Accountability and Democracy in South Asia and Beyond’, jointly organised by Stanford University and University of Mumbai on January 17-18, 2014

The writer is a former Army and IAS officer. Email: deva1940@gmail.com

IAS (retd) with a distinguished career of 40 years - worked in Army, Govt, Private, Politics & NGOs.