STAND up, India was the message when Prime Minister Narendra Modi started the Start-Up India’ campaign on January 16. The amount of Rs. 10,000 crore for five years that he earmarked at the rate of Rs. 2,500 crore a year may look far short of the requirement to help India’s youth—400 million of them, half of them school-going children—stand up in the global workplace through Indian start-ups. But the greatness of an idea has never been measured in terms of the money allocated for it; it’s always measured in terms of the quantum energy that it releases, inspiring society to take up the idea, nourish it and promote it. In this case, if thousands of start-ups bloom, they would fill the huge gap in the employment chain and unleash a huge wave of demand and services from the bottom of society to fuel exceptional growth in the real economy. Even if a few thousands of these start-ups wilt and die, many more will survive and flourish like orchards in the heart of the economy. Even if most of them die as forecast by doomsayers, the survival of hundreds of the fittest among them would change the economic landscape. That’s what the gamble is all about and it may well pay off, if one goes by things already visible on the ground.

Read this story. The youngest Indian CEO is 10 years old and the CTO just 12! Brothers Abhijit Premji (10) and Amarjit Premji (12) from Kerala have already set out on their entrepreneurial journey, making toys. India imports much of these from China and pays as much as $2 billion to keep the dragon amused at the lack of Indian ingenuity. The children were invited to Delhi to be part of the Start-Up India event, their father being one of the key personnel of the Digital India campaign. Forget for a moment their father Premjit’s station in life. Soon after returning from the Start-Up summit, the two brothers laid the foundation for Indian Homemade Toys (IHT). Yes, you heard it right: they insisted they wouldn’t sell Chinese toys, that they would only sell India-made toys. According to CEO Abhijit, IHT will not just be an online store but also a source of creativity for kids, whereas Amarjit says that his company is not a start-up but a smart-up because its mission is to encourage children to be innovators.

After a not so good year, Indian start-ups have roared into 2016. The first month of the new year has drawn about $300 million into new and old start-ups

Have patience before these stories multiply and you will be confounded by your own lack of understanding of the creative side of young India.

After a not so good year, Indian start-ups have roared into 2016. The first month of the New Year has drawn about $300 million into new and old start-ups. ShopClues hit headlines some time ago as it breached the revered unicorn club following fresh funding; it’s now valued at $1.1 billion. While e-marketplaces seem to hog the limelight, other categories, such as online grocers, hotel booking, travel, transportation, and so on, are also biting into their share. Significantly, no single player seems to be the master of all it surveys. Despite the presence of dominant players like Flipkart, Amazon and Snapdeal, Paytm and ShopClues have not just stayed competitive but have also grown. Numbers speak the same story in other sectors too—two-and-a-half-year-old hotel aggregator brand OYO Rooms got its 1,000,000th check-in last month, while six-year-old online travel aggregator Goibibo this year crossed 1.6 million room nights in Q3, at an annual growth rate of 400 per cent. Automobile classifieds sector seems to be getting attention too: online platform CarTrade raised Rs. 950 crore a few days ago. With enough space to accommodate multiple players, all sectors—from groceries to luxury—are inviting more start-ups.

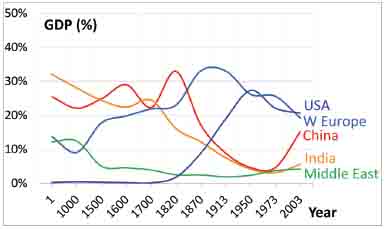

WILL it help India regain its old share in global GDP? Renowned historian Angus Maddison, in his two-volume treatise on the world economy, has shown how and why the national income of India skidded from 27 per cent of global income in 1700 to three per cent in 1950. Between 1950 and 2003, India’s share of global GDP staggered around the three per cent level even as its population quadrupled. Nothing seemed to have worked between 1950 and 1990. The planned economy of the Fifties, Sixties and Seventies unleashed two major food crises in the first two decades after Independence, forcing India to go twice for IMF loans for structural adjustment in the early Eighties and early Nineties, spawned urban slums and generated a sub-Saharan level of national income.

Something was urgently required to be done when New Delhi found itself literally bankrupt in late 1990 and early 1991. And then began India’s story of rediscovering the worth of the individual as the most potent tool of economic activity. The process of dismantling the instruments of shackling individual and family enterprises through what was famously called the “licence-permit Raj”, was kicked off by a visionary and accidental Prime Minister, PV Narasimha Rao, and his economics professor, Manmohan Singh. This rejuvenated the system and kick-started a dormant economy. Soon, what was dubbed the “Hindu growth rate” by renowned economist Prof Raj Krishna, was replaced by a “secular growth rate”; the economy accelerated from the average GDP rise of three per cent a year to six per cent; and since then it has remained in that orbit with yearly fluctuations; sometimes providing it with the tailwind to speed up to eight per cent. Not a bad performance, but not good enough to sort out the problem of mass poverty and stave off a demographic catastrophe looming large over the country.

Start-ups may open up vast marketing opportunities for software professionals, but they are not going to resolve the problems triggered by the slow growth of real economy, which is agriculture and manufacturing

Let’s face the facts. Despite a series of policy initiatives since 1980, they have proved less than adequate to place the growth rate in a higher sustainable trajectory. Over 10 governments, India’s GDP has refused to grow in excess of an average of 6.2 per cent a year over the 35-year period (Chart 1). The only time that it grew above 8 per cent was during UPA 1, when the BRIC story was hot and money was flowing into Indian IPOs and capital markets from domestic and international sources. Further analysis could throw up extremely discomforting facts about the growth spurt in 2004-9. That unfortunate period in our recent history was marked by a strong resurgence in crony capitalism as coal, iron ore, oil and gas, real estate and spectrum were given away to illustriously notorious businessmen. What was revealed subsequently in various reports of the country’s accountant, the Comptroller General of India, stunned the whole nation and made one recall the nasty prediction made by eminent British politician Winston Churchill at the time power was being transferred to Indians from British hands. “Power will go to the hands of rascals, rogues, freebooters; all Indian leaders will be of low calibre and men of straw. They will have sweet tongues and silly hearts. They will fight amongst themselves for power and India will be lost in political squabbles. A day would come when even air and water would be taxed in India.” The GDP real growth rate across 10 governments has been 6.2 per cent per annum over the past 35 years—6.5 per cent is a good, long-term assumption.

Against this background there rode to power Narendra Damodardas Modi, promising to change everything and ensuring “good days” for everyone. What he didn’t realise was that he had promised the moon, while the country was still in the throes of an extremely regressive political and economic regime. In the past 20 months or so, the Prime Minister has taken the country forward on the road to reform. But, results are eluding him because these reforms are still far less than “Yeh dil mange more”. In a very disingenuous and cynical way, his administration has changed the old system of GDP computation that seemed to inflate the growth figure. This measure has now attracted the criticism of the country’s top money manager. An intellectually honest man to boot, RBI Governor Raghuram Rajan couldn’t help commenting recently that “… we have to be a little careful about how we count GDP because some time we get growth because people (are) moving into different areas. It is important that when they move into different areas, they are actually doing something which is more value added. If mother A went to look after the children of mother B and mother B went to look after the children of mother A, and they each paid each other an equal amount, GDP would go up by the sum of the two salaries. But would the economy be better off? Presumably, kids want their own mother rather than the neighbouring mother. And the economy would be worse off.”

SIMILARLY, Modi’s new scheme of UDAY (Ujwal Discom Assurance Yojana) is also seen as a gimmick. It is yet another name for the old schemes of bailing out power distribution companies through taxpayers’ money; and, it’s the first sign of crony capitalism creeping in again. After losing the Bihar election in which he sought to play Lalu-style politics, he seems to be reverting to Lalu economics. Instead of introducing the policy frameworks to force distribution companies to address the issue of imbalanced tariffs, he is doling out government charities. In this game, he would not be able to beat the Congress, much less Lalu Prasad.

To get 8-10 per cent growth, Modi will either need to tread the tried and tested path of the UPA’s crony capitalism, or put true reforms in place. So far, he has shown little appetite for the latter. True reforms will involve beginning from the bottom—reforming agriculture and archaic colonial, socialist and corrupt laws that pressure down its performance; freeing food prices from clutches of government subsidies; disallowing capital subsidies and tax breaks and replacing them with wage subsidies in case it is required; huge investment in two-three frontier areas of technology along with a quantum improvement in standards of higher education; stoppage of commodity exports to ‘best benefactor” China; and stop shirking from taking hard decisions in foreign policy and military matters. It’s not a comprehensive list and one is sure that the government has a large pool of qualified people to advise it to do what it would take before we effortlessly move into the higher growth orbit of 8-10 per cent.

Quick fixes are quick fixes; they aren’t a solution to long-term structural problems. For instance, the Prime Minister’s latest love, start-ups, however desirable they may be, are not going to solve the fundamental problems of this country. They may open up vast marketing opportunities for software professionals, but they are not going to resolve the problems triggered by the slow growth of the real economy, which is agriculture and manufacturing. The start-ups could help create demand by expanding e-commerce, create a few lakh jobs in allied areas, and could even add a few percentage points to GDP, but they would not be effective unless they are backed by an effective and efficient manufacturing chain. And, unfortunately, there has been little private capital formation in the last 20 months of his stewardship. It’s not the RBI’s monetary policy that is generally blamed; it’s the inability of the government to set in motion true structural reforms.