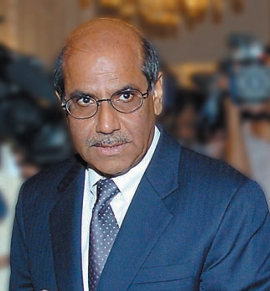

Former Foreign Secretary Shyam Saran belongs to the 1970 batch of the Indian Foreign Service. He served at the MEA as Joint Secretary, heading the Economic Division, the Multi-Economic Relations Division, and the East Asia Division. He was also Joint Secretary in the PMO, looking after External Affairs, Defence and Atomic Energy From 1992 till 2004, he was India’s envoy to Mauritius, Myanmar, Indonesia and Nepal.

Thereafter, he was Foreign Secretary till September 2006. Since October 2006, he has been the Prime Minister’s Special Envoy on the Indo-US nuclear deal Holding a postgraduate degree in economics, he knows Chinese and French due to his various assignments.

gfiles:What is the original motivation behind the nuclear deal and its implications for our strategic programme?

Shyam Saran: Ever since India and the US declared their intention to resume bilateral cooperation in civilian use of nuclear energy on July 18,2005, there has been a national debate on India’s place in the nuclear domain.This debate is welcome.It enables public opinion to be educated on what has remained a relatively esoteric field.Attention has been focused on the significance of nuclear energy in achieving energy security.There has also been scrutiny of our strategic weapons programme.

‘Our objective is to enable

India to have a wide choice of

partners in pursuing nuclear

commerce, and high technolo

gy trade. But we cannot attain

this objective without the US

taking the lead on our behalf’

gfiles:How does India gain from the deal?

SS: Let me share with you the mandate which Prime Minister Manmohan Singh gave us.Since 1974,India had been the target of an increasingly selective, rigorous and continually expanding regime of technology-denial, not only in the nuclear field but encompassing other dual-use technologies.It was our aim to seek the dismantlement of these inequitable regimes.In pursuing this objective,we were aware that:(i) The multilateral technology-denial regimes whose targeting of India we sought to end such as the Nuclear Suppliers’ Group (NSG) and the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR) would require the US to take the initiative as the principal initiator and leader of these regimes, and also because it remains the world’s pre-emi nent source of new and innovative tech nologies. (ii) Since our PNE in 1974, technology denial was first limited to nuclear-related technologies and then expanded to cover a growing range of dual-use technologies. Unless we tack led the nuclear issue, we would not be able to obtain access to other useful technologies.

We were becoming increasingly aware that we would face a progressively more depleted market for conventional ener gy resources. Concerns over climate change would act as a further constraint on us. We had to adopt a strategy of diversifying our energy mix, with a graduated shift from fossil fuels to non fossil fuels, from non-renewable to renewable sources of energy and from conventional to non-conventional sources of energy.Nuclear energy occu pies a key place in this strategy. Despite the technology-denial regimes, our sci entists had put in place a comprehensive, sophisticated and innovative nuclear industry, with highly trained manpower able to sustain a major expansion in nuclear power. Our constraints in this regard were availability of domestic ura nium and a technological capability still limited to smaller-capacity reactors of about 700 MW, when the world was moving to 1600 MW reactors. If we were to envisage a major expansion in nuclear power in the medium term,to, say, 60,000 MW plus by 2030, then import of higher-capacity reactors and uranium fuel would be necessary.

gfiles: Will we not detract from Homi Jehangir Bhabha’s vision?

SS: This in no way detracts from the continued pursuit of Dr Bhabha’s visionary three-stage nuclear energy development programme, which may yield significant results in the longer term. But in the short and medium terms,a significant expansion of nuclear power is only possible if the constraints we face on import of uranium and of large-capacity reactors are removed. Furthermore, it is not really correct to put indigenous development and inter national collaboration as antithetical to one another. Dr Bhabha himself vigor ously promoted international coopera tion in nuclear energy which enabled India to lay the foundation of our cur rent nuclear programme.

gfiles:Are we accepting any limits? And what is the implication?

SS: We are not accepting any limits. We (negotiators) were given a firm guideline that we should not accept any limitation whatsoever on our strategic weapons programme, which must remain inviolate and fully autonomous. It implies that: (i) our strategic weapons pro gramme would be outside the purview of any international safeguards regime or any form of external scrutiny; (ii) our ability to further develop and produce such weapons would not be constrained in any manner; and (iii) we would retain our legal right to conduct a nuclear test should that,at any time in the future,be deemed necessary in our overriding national interest. It was felt that, this being a programme which had major potential for commercial exploitation of thorium-based nuclear energy in the future,we ought to safeguard its integri ty for the present.

gfiles: What assurance have we given that the deal will be finalized?

SS: The July 18 Joint Statement incor porated a series of reciprocal commit ments.On India’s side,there was reaffir mation of some existing commitments, such as continuing a moratorium on nuclear testing and participating in mul tilateral negotiations on a Fissile Material Cut Off Treaty.There was acknowledge ment of steps already taken by India as part of its responsibilities under UNSC resolution 1540 and under the already concluded Next Steps in Strategic Partnership.These relate to strengthen ing controls on the export of sensitive technologies,including reprocessing and enrichment technologies.These controls provided assurance to our partners that whatever we received under interna tional cooperation would not be divert ed to third countries.

The new element was our commit ment to separate our civilian and mili tary nuclear facilities and offer the for mer voluntarily for IAEA safeguards. This was necessary for us to give our international partners the assurance that whatever we would receive as technolo gy or equipment for our civilian facili ties would not be diverted to benefit our strategic programme. This was, in our mind, a legitimate expectation on the part of the international community. Nevertheless, we reserved the right to determine which facilities would be designated as civilian;further,the separa tion process would be carried out in graduated steps up to 2014 so as to avoid any dislocation in our nuclear industry.

gfiles: What has India obtained till now?

SS: Reciprocally, in return, was a US commitment to adjust its own laws so as to permit full civil nuclear energy coop eration with India,which is bilateral;and also a commitment to work with friends and allies to bring about a change in international, multilateral regimes such as the NSG to enable the international community to also engage India in full civil nuclear energy cooperation,which is multilateral.With the US delivering on these commitments, India will become fully integrated into the global nuclear energy market after a gap of over 40 years.And it will be able to achieve this without accepting any limitation or constraint on its strategic weapons pro gramme.

The July 18 Joint Statement was then translated into more elaborate and spe cific arrangements in a Separation Plan,presented to Parliament in March 2006 and in the text of a bilateral cooperation agreement, or the so-called 123 Agreement between India and the US concluded in July 2007. In practical terms, this meant ensuring that there would never again be a threat of reactor operations being disrupted due to sus pension of fuel supplies. We will also need to ensure that India has the right to reprocess foreign-origin spent fuel. In both respects, the US-aided Tarapur nuclear facility had suffered and this hung over the negotiations as a negative legacy.There had been US unilateral sus pension of fuel supplies,just as there had been a refusal to allow India to reprocess spent fuel, which kept accumulating as hazardous waste,which the US was also not willing to take back.

gfiles: But the general impression is that India has agreed to permanent IAEA safe guards on its civilian facilities

SS: We are aware of this. Our position from the outset had been that we have no problem with permanent safeguards, provided there are permanent supplies of fuel.The multi-layered fuel supply assur ances are unique in international nuclear negotiations and include India’s right to take “corrective measures”, should any disruption still occur despite these assur ances.India’s entitlement to build strate gic reserves of fuel for its civilian reac tors, to last the lifetime of such reactors, is also unique.

‘India will become fully

integrated into the glob

al nuclear energy market

after over 40 years. And

it will be able to achieve

this without accepting

any limitation or con

straint on its strategic

weapons programme’

gfiles: Don’t you think you have buckled to the various provisions of the Hyde Act? It is argued that, irrespective of what the 123 Agreement may say, India will be subject to the several onerous provisions of the Act.

SS: The operative heart of the Hyde Act incorporates three permanent and unconditional waivers from relevant provisions of the US Atomic Energy Act of 1954.Simply,we can say the Hyde Act allows the US Administration to engage in civil nuclear cooperation with India, waiving the following requirements: (i) that the partner country should not have exploded a nuclear explosive device in the past;this waiver is necessary because India exploded a series of nuclear explo sive devices in May 1998; (ii) that the partner country must have all its nuclear facilities and activities under full-scope safeguards; this waiver is necessary because India has a strategic programme which would not be subject to interna tional safeguards, nor would its indigenous R&D programme;and (iii) that the partner country is not currently engaged in the development and production of nuclear explosive devices; this waiver is required because there is no freeze or capping of India’s strategic weapons pro gramme.It is an acknowledgement that we will continue to develop and pro duce additional strategic weapons. Irrespective of what else the Hyde Act may contain,these three permanent and unconditional waivers are extremely sig nificant because they acknowledge that India has an ongoing strategic pro gramme. No restraint on this pro gramme is envisaged as a condition for engaging India in civil nuclear energy cooperation.This is a significant gain for India and should not be lost sight of.Just juxtapose this with the UNSC Resolution 1172 of June 6,1998,which called upon India to stop, roll back and eliminate its strategic programme and join NPT as a non-nuclear weapon state.

gfiles: Will the US Congress agree to the amendments in the Hyde Act?

SS: Of course,there are several extrane ous and prescriptive provisions in the Hyde Act which we do not agree with and in negotiating the 123 Agreement we have been more than careful to exclude such provisions. If the US Congress considers the 123 Agreement, as currently drafted, as being in contra vention with their own understanding of the Hyde Act, the agreement would be voted down.That would be the end of the matter. If, however, Congress does approve the 123 Agreement, then this would confirm that the provisions of the Agreement are what would govern the commitments of the two sides.

gfiles: What are we aiming for?

SS: Our objective is not merely to seek the US as a partner.Our objective is to enable India to have a wide choice of partners in pursuing nuclear commerce, and high technology trade.But we can not attain this objective without the US taking the lead on our behalf.Yes,Russia and France are countries which are friendly to India and extremely keen to engage in nuclear commerce with us. However,there should be no doubt that neither they nor others will make an exception for India unilaterally unless the Nuclear Suppliers’ Group adjusts its guidelines in the same manner as the US is prepared to do.Whatever be the reser vations expressed about our relations with the US,no other friendly country, member of the NSG has the necessary standing to lead the process of opening up the existing multilateral regime to accommodate India.

gfiles: Why should we deal with the US and not the NSG alone?

SS: The US is in a unique position pre cisely because it initiated these restrictive regimes in the first place and also because it remains the pre-eminent source of new sensitive technologies.

gfiles: So how will you reach the final agree ment?

SS: The process we are engaged in will face several challenges even if the con troversies at home were somehow resolved.We still await the finalization of the India-specific safeguards agreement with the IAEA.Thereafter,the NSG will meet to consider exempting India from its current guidelines.These guidelines, like pre-Hyde Act US legislation, require that its members engage in civil nuclear energy cooperation only with countries that have all their nuclear facil ities and activities under full-scope safe guards. It is our expectation that there would be a fairly simple and clean exemption from these guidelines, with out any conditionalities or even expec tations regarding India’s conduct in future. Finally, the US Congress has to vote to approve the 123 Agreement. Only when these separate landmarks have been achieved, can we really have the practical possibility of resuming civil nuclear energy cooperation with the international community.

gfiles: What enabled India to even attempt such a pathbreaking initiative? Would it not have been more prudent to engage in incre mental pursuit of more limited gains which would cumulatively add up to something sig nificant eventually?

SS: In pursuing this initiative in 2005, India took advantage of a significant change in international, including US and Western, perceptions of India. First, 15 years of accelerated and sustained economic growth, coupled with the steady globalization of the Indian econ omy, marked India’s emergence as an economic power-house,even as its dem ocratic structures gave it a reputation for political stability.The prospects for con tinued and steady growth of India’s economy made it an indispensable part ner for countries across the globe. Second, a globalizing world found itself confronted with a number of transna tional, cross-cutting issues such as inter national terrorism, drug trafficking, global pandemics and the twin chal lenges of energy and climate change.In seeking solutions to such global chal lenges,the active involvement of India as a large, populous and continental-sized economy, has become indispensable. This is another reason India’s global pro file has increased. Third, India had emerged as a country with significant defence capabilities and has an enviable record of activism in UN peacekeeping. In December 2004,its swift response to the tsunami and its ability to extend significant assistance to affected countries also demonstrated its capabilities to con tribute to maritime security and help deal with natural disasters. Fourth, despite a four-decade effort to put India in a technological corral and constrain its nuclear and space capabilities, Western countries led by the US had failed to achieve their objective.

Technology denial may have slowed down India’s development in some respects,but on the other hand India was now a country with a wide range of sophisticated and sensitive technologies, isolating which made no sense,particu larly at a time when engaging India promised much more by way of political and economic gains, not the least by partnering its outstanding scientists in the collaborative development of cut ting-edge technologies such as the International Thermo Nuclear Energy Reactor (ITER) project. India was able to get a clear message across to the world– you cannot continue to treat India as a target, even as you seek to engage it as a partner.These entities had so far exclud ed India such as the UN Security Council or, worse, targeted it as an adversary like the NSG.

gfiles: What is the likely role of nuclear weapons in ensuring India’s security?

SS: The traditional concept of nuclear deterrence is with reference to States and that is how we have defined our deterrent as well. However, even in this respect, our nuclear doctrine affirms India’s conviction that its security would be enhanced,not diminished,if we were able to achieve a world free of nuclear weapons. It is this conviction which underlines our continued advocacy of nuclear disarmament. While asserting our right to a nuclear deterrent, we should not forget this other dimension of our security posture.

gfiles: How do you threaten nuclear retali ation against such non-State actors?

SS: The danger posed by proliferation of nuclear weapons to non-State actors is of a different and more threatening dimension than that from proliferation to additional States. India has all along argued that,as long as the world is divid ed between those who possess nuclear weapons and those who do not, there will always be a strong incentive for countries outside the club to seek to enter it. Recent experience indicates that the NPT and technology-denial regimes may delay the emergence of new nuclear weapon States but are unlikely to prevent it.

As long as there exists such motivation among States, there will inevitably be a clandestine market for nuclear technology and material,as demonstrated by AQ Khan’s nuclear supermarket If such a clandes tine market continues to flourish, as it does even today, the danger of nuclear explosives or fissile material and techni cal know-how enabling the manufac ture of nuclear weapons falling into the hands of non-State actors,such as jehadi groups, will continue to haunt our world.India has to be deeply concerned about the danger it faces, as do other States,from this new and growing threat. In 1965,when India sponsored nego tiations on a Non-Proliferation Treaty,it proposed that non-nuclear weapon States should commit themselves to never developing or acquiring nuclear weapons,in return for a legal and time bound commitment by nuclear-weapon States to eliminate their arsenals.Today, as a nuclear-weapon State, India is in a unique position to take the lead in res urrecting the original grand bargain because the danger of nuclear terrorism threatens to engulf all States.

India’s security was also being threat ened by clandestine proliferation in its own neighbourhood, without any remedial action being taken at the inter national level. In a world populated by States producing and deploying nuclear weapons, India’s strategic autonomy must be safeguarded. However,we must not forget that, despite being a nuclear weapon State, India remains convinced that its security would be enhanced,not diminished, if a world free of nuclear weapons were to be achieved.Today,the country’s security is further threatened by the risk of proliferation to non-State actors and terrorist groups.So also is the security of all other States. It is only through the urgent and complete elimi nation of nuclear weapons that it may be possible to minimize,if not entirely dis pel, the threat of nuclear terrorism by non-State actors.

‘Our position from the

outset had been that we

have no problem with

permanent safeguards,

provided there are per

manent supplies of fuel.

The multi-layered fuel

supply assurances

are unique’

gfiles: It is a billion-dollar deal. It is said that we are under pressure to push it because the US wants it.

SS: It is absolutely incorrect and those making this criticism are not aware of the facts. It will all depend on what reactor and technology we buy. If we are choosing to buy a 1600 MW reac tor then we have to plan from which country we are going to buy. Cost varies due to many aspects:technology, country, contract conditions etc.There have been estimates in the media that if petrol remains above $45 per barrel then it is cost-effective to have nuclear power and one can understand what the price of petrol is today.

gfiles: How much time will it take to sign the 123 agreement?

SS: It is not proper to say how much time it will take.We are trying for it to be signed as soon as possible.