When Parliament passed the Sabka Bima Sabki Raksha (Amendment of Insurance Laws) Bill, 2025—with Rahul Gandhi and Prime Minister Narendra Modi both absent from the decisive vote—it rewrote India’s insurance landscape. Backed by decades of external corporate lobbying and foreign industry pressure, the bill’s 100% FDI clause is poised to transform an essential public service into a global capital playground. As India eyes “Insurance for All” by 2047, who truly gains?

India’s Parliament slipped through one of the most consequential financial sector reforms of the decade when, late in December, legislators approved the Sabka Bima Sabki Raksha (Amendment of Insurance Laws) Bill, 2025. The measure raises the foreign direct investment (FDI) ceiling in the insurance sector from 74% to 100%, ostensibly to attract capital, expertise, and expand coverage in a country where insurance penetration remains low.

Conspicuously absent from the decisive vote were two towering political figures: Rahul Gandhi, long an emblem of opposition resistance, and Prime Minister Narendra Modi himself. Neither was present when Parliament approved what may become one of the most transformative economic reforms of the next quarter-century. Their absence invites questions about political ownership of the policy and the influences that shaped it.

A Policy with a push of international lobbyists

The narrative of insurance liberalisation isn’t a recent development sprung from technocratic necessity. It has roots deep in decades of international advocacy and corporate pressure.

Figures like Frank G. Wisner, former U.S. ambassador to India and later vice-chairman for external affairs at American International Group (AIG), were publicly associated with efforts to open India’s insurance market to global capital as early as the 1990s and 2000s. In his role with AIG, Wisner became one of the foreign executives pushing for greater access to the Indian market—arguably helping normalise calls for liberalisation.

Global insurance industry lobbies have also consistently backed deeper reforms. The Global Federation of Insurance Associations (GFIA) has repeatedly encouraged steps that remove barriers to foreign ownership and investment, arguing that such reforms would “boost foreign investment and modernise the industry.” Their letters to Indian authorities have targeted restrictions like board composition, citizenship requirements for senior management, and unequal tax treatment—framing these as obstacles for foreign insurers.

On the corporate side, executives such as Susan Greenwell of MetLife—who has served in senior international government relations roles—have championed the benefits of regulatory openness in multiple markets, including India. Exactly how these corporate advocacy efforts influenced Indian policymakers is opaque, but such voices form a veritable backdrop to the policy momentum.

Even Brad Smith as an international industry advocate representing global insurance interests through ACLI and as Chair of the GFIA Trade Working Group, he has co-authored letters and positions encouraging regulatory reforms—including FDI liberalisation—that align with broader foreign insurance sector interests. He has participated in discussions organised by CII in May 2025.

The Bill’s Ambitions and the Real Stakes

Supporters of the reform argue that freeing foreign capital will bring much-needed capital and innovations, enabling insurers to underwrite more risks and extend coverage to underserved populations. The government and the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India (IRDAI) have tied this push to the broader goal of “Insurance for All by 2047”—a target aligned with the centenary of India’s independence.

India’s insurance sector has indeed grown rapidly: premiums reached nearly ₹11.93 lakh crore and assets under management swelled past ₹74 lakh crore in 2024-25, making the country one of the world’s largest insurance markets by size. But these figures mask persistent gaps: despite growth, insurance penetration remains below global averages and millions lack meaningful coverage.

Looking forward, long-term projections suggest a potentially massive industry by 15 August 2047—with some estimates pointing to a market worth around $2 trillion in premiums annually (roughly ₹1.6 Crore lakh crore at current exchange rates) if India can raise penetration to global norms. Such scale would dwarf today’s numbers, making insurance one of India’s most valuable financial sectors.

Yet it is precisely this future prize that has attracted sustained foreign interest and lobbying. If the sector truly approaches $2 trillion in annual premiums by 2047, the eventual beneficiaries could shift from domestic policyholders to global shareholders unless robust consumer protections are instituted.

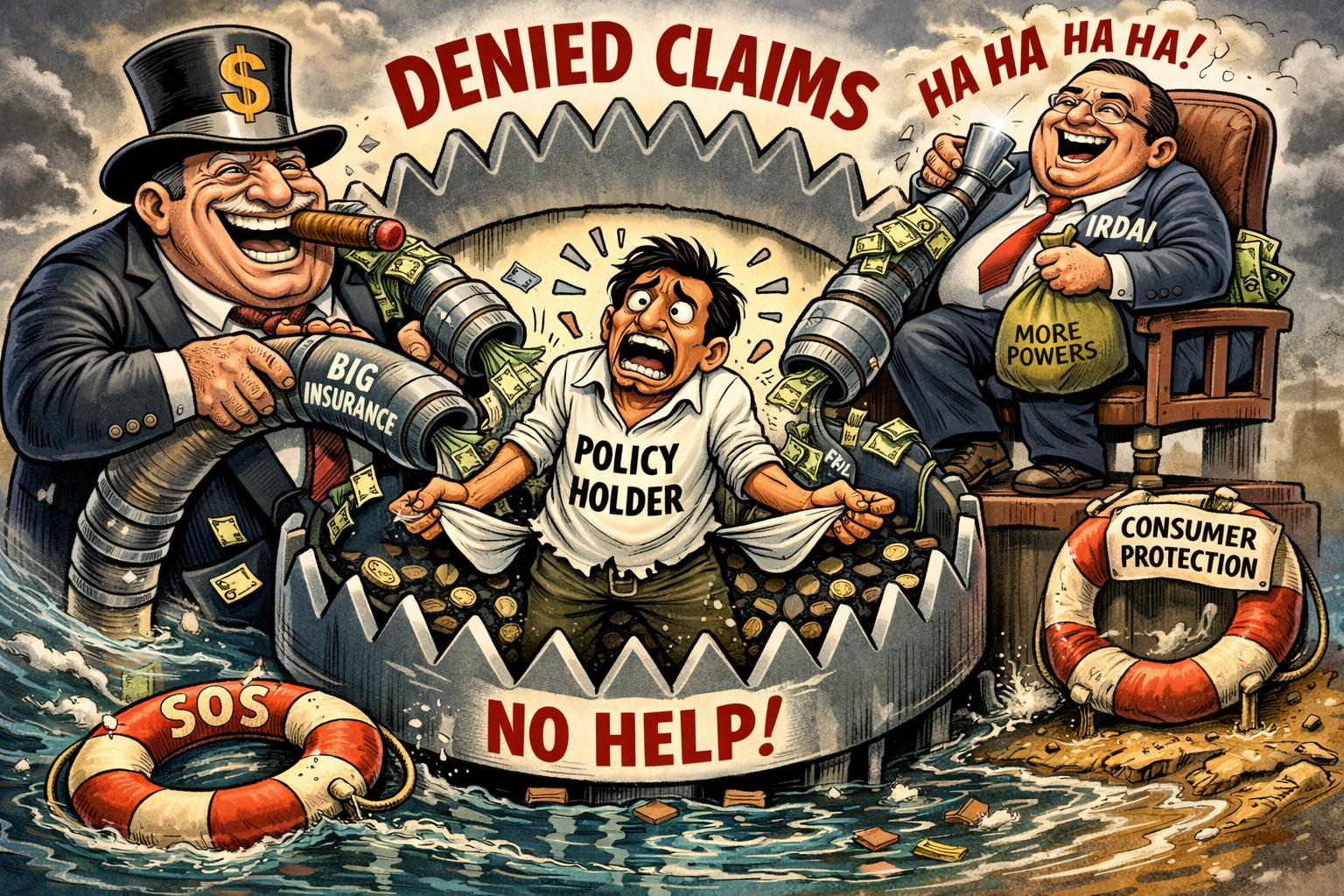

Whose Protection?

Critics argue that despite its name, the “Sabka Bima Sabki Raksha Bill” may do less for everyday Indians than for multinational insurers and investors. With full ownership rights, foreign companies could repatriate profits and dictate strategy without mandatory domestic participation. Regulatory safeguards—once designed to protect local markets—are now being reassessed under pressure from industry groups eager to compete on a level that favours global capital.

The IRDAI, tasked with safeguarding policyholders, has been empowered with new supervisory tools under the bill. But critics fear these powers may not be enough if the balance of power decisively shifts toward well-resourced international players.

A Reform Without Consensus

The bill passed without a full political reckoning, and the absence of key leaders during the vote suggests political convenience trumped consensus. If the goal is truly to protect Indian citizens, that objective deserves more than a quiet vote and a future-focused tagline.

India’s insurance future could be bright, but it needs policies that ensure protection first, profits second—not reforms that open doors wide enough for global capital to dictate terms, with public safeguards left behind.

Editor, gfiles