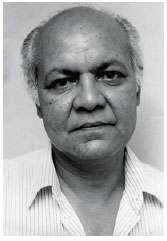

Janardan Thakur started his career in journalism with the nationalist Patna daily, The Searchlight, in December 1959. In his long and distinguished career spanning the reign of each Prime Minister since Independence, Thakur reported from the thick of some of the most momentous contemporary events at home and afar—JP’s ‘total revolution’, the Emergency, the bristling emergence of Sanjay Gandhi, the fall and rise of Indira Gandhi and then the rise and fall of Rajiv, the Kremlin of Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and Khomeini’s revolution in Iran, Ronald Reagan’s re-election in an America swinging Right, VP Singh’s ascent as a messiah with tainted magic and the rasping run to power of the BJP. Thakur’s journalism, from the very start, broke traditional moulds of reportage and writing, going beyond the story that meets the eye and into processes and personalities that made them happen. His stories on the Bihar famine of the mid-1960s and the manmade floods that ravaged the State were a sensation. He was perhaps alone in predicting defeat for Indira Gandhi in 1977 and again singular in exposing the corroded innards of the Janata Government that followed. A Jefferson Fellow at the East-West Center, Hawaii, in 1971, Thakur moved to New Delhi as a Special Correspondent for the Ananda Bazar Patrika group of publications in 1976. He went freelance in 1980 and turned syndicated columnist. In 1989-91, he was Editor of the fortnightly Onlooker, and The Free Press Journal. Thakur authored All The Prime Minister’s Men, probably the most successful of the crop of books that followed the Emergency. His All the Janata Men, the story of the men who destroyed the first non-Congress government in New Delhi, was equally successful.

Janardan Thakur started his career in journalism with the nationalist Patna daily, The Searchlight, in December 1959. In his long and distinguished career spanning the reign of each Prime Minister since Independence, Thakur reported from the thick of some of the most momentous contemporary events at home and afar—JP’s ‘total revolution’, the Emergency, the bristling emergence of Sanjay Gandhi, the fall and rise of Indira Gandhi and then the rise and fall of Rajiv, the Kremlin of Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and Khomeini’s revolution in Iran, Ronald Reagan’s re-election in an America swinging Right, VP Singh’s ascent as a messiah with tainted magic and the rasping run to power of the BJP. Thakur’s journalism, from the very start, broke traditional moulds of reportage and writing, going beyond the story that meets the eye and into processes and personalities that made them happen. His stories on the Bihar famine of the mid-1960s and the manmade floods that ravaged the State were a sensation. He was perhaps alone in predicting defeat for Indira Gandhi in 1977 and again singular in exposing the corroded innards of the Janata Government that followed. A Jefferson Fellow at the East-West Center, Hawaii, in 1971, Thakur moved to New Delhi as a Special Correspondent for the Ananda Bazar Patrika group of publications in 1976. He went freelance in 1980 and turned syndicated columnist. In 1989-91, he was Editor of the fortnightly Onlooker, and The Free Press Journal. Thakur authored All The Prime Minister’s Men, probably the most successful of the crop of books that followed the Emergency. His All the Janata Men, the story of the men who destroyed the first non-Congress government in New Delhi, was equally successful.

He passed away on July 12, 1999.

IF Vajpayee’s first government was a quickly aborted affair, his second one almost never came about. Celebrations in the BJP camp turned sombre as Jayalalitha, who would become a painful thorn in the government’s side, tantalisingly held back her letter of support to Vajpayee. The lady of Poes Garden had draped the new Prime Minister with a glistening gold-border angavastram and then confronted him with her long charter of demands: Make Subramaniam Swamy the finance minster; dismiss the ruling DMK government in Tamil Nadu and impose Article 356; endorse the candidature of M Thambi Durai for the post of deputy speaker; split the finance ministry into two and appoint Vazhapadi K. Ramamurthy as minister for revenue and banking; make Tamil an official language at the Centre…

Swamy was already hogging prime time on TV, acting almost as the country’s would-be finance minister. Asked if he would like to be the finance minister, he had grinned from ear to ear and said, “I would find the finance portfolio challenging.” When told that the feeling was that Jayalalitha was pushing for finance because she was worried about the array of court cases against her, Swamy said: “She’s a very capable person. She has fought her cases in court and can look after herself.”

The threat could hardly be missed. If nothing else, Dr. Swamy had a great reputation for pulling down governments: he had pulled down Ramakrishna Hegde, he had pulled down Jayalalitha herself. He had called her all kinds of names, and had even accused her of having colluded with the LTTE to get Rajiv Gandhi killed. Most of the cases she was now fighting were the handiwork of this loud-mouthed politician. Swamy had become such a menace to her that she finally decided it was in her best interest to have him on her side. Very much like John Kennedy’s decision to have Lyndon Johnson as his running mate in the presidential election and let him ‘pee inside the tent rather than outside’. Jayalalitha had surrendered to her wily antagonist and was now so set on getting him the finance portfolio in the Vajpayee government, or at worst the ministry of law, that she just sat over her letter of support, determined not to send it to the President until her demands were met. Vajpayee was equally firm. He would concede anything but not a place to Swamy in his Cabinet. Their enmity went a long way back.

The threat could hardly be missed. If nothing else, Dr. Swamy had a great reputation for pulling down governments: he had pulled down Ramakrishna Hegde, he had pulled down Jayalalitha herself. He had called her all kinds of names, and had even accused her of having colluded with the LTTE to get Rajiv Gandhi killed. Most of the cases she was now fighting were the handiwork of this loud-mouthed politician. Swamy had become such a menace to her that she finally decided it was in her best interest to have him on her side. Very much like John Kennedy’s decision to have Lyndon Johnson as his running mate in the presidential election and let him ‘pee inside the tent rather than outside’. Jayalalitha had surrendered to her wily antagonist and was now so set on getting him the finance portfolio in the Vajpayee government, or at worst the ministry of law, that she just sat over her letter of support, determined not to send it to the President until her demands were met. Vajpayee was equally firm. He would concede anything but not a place to Swamy in his Cabinet. Their enmity went a long way back.

Years ago, when Subramaniam Swamy was still in the Jan Sangh, he had launched a vicious attack on Atal Behari Vajpayee, obviously with the backing of his godfathers in the organisation. The young political climber, who had come into focus during the Emergency as a sort of ‘Scarlet Pimpernel’, became nasty after Vajpayee, then foreign minister in the Janata government, refused him permission to go to China. As Swamy related the story, “Vajpayee threw a tantrum. The Indian Embassy in Peking had sent him word that I would be given a big welcome as an anti-Soviet fighter. Vajpayee suddenly saw visions of my picture with the great Chinese leaders… He is incapable of tolerating any publicity for anybody else. Ironically, it was he who made me a member of the Jan Sangh working committee overnight, and proposed my name for the Rajya Sabha…I had been his fan…Well, I liked him, but he started feeling that I was becoming very important.” Swamy had done his utmost to tar Vajpayee’s face, and had even accused him of indulging in wine and women.

And now, Vajpayee put his foot down. No Swamy, he made it clear, support or no support, government or no government. And at that point his stock as a leader really soared, for there was no love lost between the people and Subramaniam Swamy, regardless of what he thought of himself. But Swamy had a thick hide. He arrived in Delhi and called on Advani and Vajpayee, and told them he wanted the finance portfolio. What Vajpayee said to Swamy is not known, but publicly he said, “I would rather not form a government than give in to such pressure.” He was ready to promise the lady other things, such as more cabinet berths to her party men and a hard look at the question of dismissing the DMK government. Jayalalitha was not talking about her personal predicaments at all, but she was obviously taking it for granted that a government dependent on her support could not harass her. She was pretty certain that with her man planted in the finance ministry the skeletons in her cupboard would be taken care of.

Among the skeletons were: the charge that she had used her official position to acquire government land for her publications enterprise causing the state a loss of over three crore; that she had received bribe of Rs. 8.53 crore in a deal for the purchase of over 45,000 colour television sets for village community centres in Tamil Nadu; that she had waived a fee of Rs. 2 crore due to the government from an advertising agency; that she and her associates had acquired jewellery and assets worth over Rs. 66 crore during her years in power; that she had received birthday gifts worth over a crore from unknown sources; that she had made Rs. 39 crore through the grant of quarry licences to private parties. The list went on and on. Swamy had dug up so much material against her that I had often wondered if during his stint at Harvard, he had also done an apprenticeship with the FBI.

EVERYONE could see why it was so important for the lady to control the levers of power. Vajpayee had taken a tough line because he could see that Jayalalitha did not have much room for manoeuvre. Any government at the Centre would have been reluctant to bail her out. Who wants a kiss of death?

After four days of suspense, Jayalalitha finally consented to send the letter of support. The BJP and its allies heaved a collective sigh of relief, but this was not the end of problems for Prime Minister Vajpayee. As he sat down to distribute portfolios, the RSS caught hold of his throat. Vajpayee wanted to give Jaswant Singh the finance portfolio, as he had done during his 13-day stint. Singh had already been sworn in as a Cabinet minister. But this time, knowing that the government could last longer, the hardliners in the Sangh Pariwar turned the screw. They considered Jaswant Singh too liberal and too much of a stranger to the RSS culture to get such an important place.

Besides, he had lost the election. Vajpayee again insisted, but gave in after the RSS crown prince K S Sudarshan drove to his house and made it plain that the RSS would not agree. Jaswant Singh was made to issue a letter opting out of the government “because I am not a member of any house”. For Vajpayee it was a tremendous loss of face. His place was taken by Yashwant Sinha, who was even more a stranger to the Sangh Parivar than Jaswant. But Sinha had quietly worked to win over the RSS in the months preceding the elections, regularly paying obeisance at the Jhandewalan headquarters, attending RSS functions, supporting their line in the party. The announcement of portfolios was delayed as the backstage wranglings continued.

Around this time, Vajpayee began to realise that the man he most needed to be careful of was his own No.2, Lal Krishna Advani who was ready to do anything that would discomfit the Prime Minister. The subterranean battle with Advani would become a fixture of Vajpayee’s prime ministership. He would provoke the Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Kalyan Singh against the Prime Minister and revel in organisational instability in the State. He would issue public statements on just the day the Prime Minister sent Jaswant Singh to make peace with Jayalalitha. Advani forced the Cabinet’s hand on Bihar and kept encouraging Governor S S Bhandari to speak against the Rabri government even after the President had sent back the recommendation on imposing President’s Rule. After the Prime Minister returned from his US tour, his office made it clear that he was not for President’s rule in Bihar, but Advani and his people kept saying that the issue was still open. Even on the nuclear bomb—the single most important event of Vajpayee’s premiership—Advani embarrassed the government by linking it to the Kashmir issue and publicly warning Pakistan. Advani’s statement sharpened international attack on India and provided Pakistan greater justification to go ahead with its own tests.

IT had been out of sheer compulsion that the BJP hardliners had swallowed the projection of Vajpayee as their prime ministerial candidate. Before the 1998 Lok Sabha elections, the BJP had taken several hard knocks: first, the Vaghela revolt in Gujarat, then the growing factionalism in Maharashtra, then the abrupt end to backseat driving in Uttar Pradesh, and on top of it the shenanigans in their attempts to form a government in the State. Advani had been jubilant over what he described as the ‘UP coup’, but when Kalyan Singh formed a 93-member ministry, and a committee was set up to discuss it, Vajpayee refused to have anything to do with it. He had shown his disapproval of Kalyan Singh inducting history-sheeters into his ministry, and one of his supporters had remarked: “If one had to get into this kind of aggressive horse-trading in UP, why did it (the party) have such a holier-than-thou attitutude when Vajpayee was Prime Minister?” Obviously when Vajpayee had been given 13 days’ time to prove his majority in the Lok Sabha, the hard core of the Sangh had suddenly become very puritan about any horse-trading to boost the strength of the alliance.

Strains had also developed between the BJP and the RSS because of the unseemly factional wrangled in Gujarat. Some sections in the RSS perceived the removal of Keshubhai Patel as a whittling down of its authority, and were far from reconciled to the change. While some in the BJP saw it as an assertion of the party against the ‘remote control’ by the hardcore Sanghites, others were worried about the future implications of the ‘unhappy strains’ between the two.

The Shankarsinh Vaghela episode gave people a new insight into what the BJP could soon become. For the BJP president, L K Advani, it was much more than just a loss of face. He and his supporters had thought Gujarat was the bastion from which they would launch their final assault on the Centre. But suddenly Vaghela had thrown not just Gujarat into the melting pot but even put a big question mark on the party’s future in the poll battle to come. What was more, when it came to the crunch it was Atal Behari Vajpayee’s intervention which averted a crisis, at least for a time.

To rewind a little, the party’s upbeat mood before the crisis in Gujarat had much to do with the change in the attitude of the RSS, after Prof. Rajendra Singh became the Sarsanghachalak. Perhaps for the first time since the Lok Sabha elections of 1977, the Sangh Parivar had resolved to put all its strength behind the BJP in the next Lok Sabha elections. Over the years, the RSS had remained essentially apolitical; quest for power had not been its main priority. Even now there are people in the organisation who believe that it is not for them to indulge in politics, as this goes against its main objective : Nation building. Indulging in politics, in their view, is bad for inculcating discipline and character-building, which are supposed to be the prime concerns of the RSS. Getting involved in politics and fighting elections are ‘not our business’. An exception was made, for the first time in 1977, because of the abnormal circumstances in which the Lok Sabha elections were held —after one of the most trying ordeals that the organisation had ever faced during the Emergency. The RSS was in absolute disarray. Suddenly released from the trauma, it had been galvanised into unprecedented activity, which became a major factor in Indira Gandhi’s electoral debacle in March 1977.

After the victory of the Janata Party, there was again a change in the attitude of the RSS towards politics: a swift disenchantment as a result of the ragtag nature of the government and the growing wrangles between the various components of the Janata Party. The Jan Sangh had become just one of the jarring notes in a totally discordant orchestra. By the end of 1979, the dejection was so deep that the top RSS leaders even scoffed at their cadre getting too involved in the BJP’s election campaign The indifference of the RSS to the prospects of the Jan Sangh in its new avatar was a major factor in its dismal performance in the 1984 Lok Sabha elections, when it hit rock bottom: two seats in the Lok Sabha. It was not just indifference, but even positive distaste for the BJP, which was trying hard to become an umbrella party like the Congress. Some RSS leaders thought Indira Gandhi had become a better Hindu leader than some of the top men in the BJP!

In later years, there was again a shift from that position, more so after the BJP became an unabashed champion of Hindutva. With the change of guard in the RSS, the pace of change quickened. The new RSS chief activated the various front organisations and gave a political orientation to their action plans. Prof. Rajendra Singh was convinced that the forces of Hindutva had reached a decisive point in their quest for power.

The ‘real face’ of the renascent BJP was Lal Krishna Advani. His entire persona had changed after the Rath Yatra. Not only had he become an articulate speaker, albeit a raucous one, but had even demonstrated that he could draw crowds, especially those enthused by the new surge of Hindutva. They all thought Advani’s senior colleague, Atal Behari Vajpayee, was simply not cut out for the born-again spirit.

ADVANI’S ascendance in the party had actually started after the electoral debacle of 1984, in which the party slumped to just two members in the Lok Sabha. Vajpayee himself had been licked by the young Madhavrao Scindia. After a great deal of ‘heartsearching’ the party ideologues came to the conclusion that Vajpayee who had been given the baton in 1980 had misled the BJP and turned it into neither fish nor fowl. They thought he had destroyed the organisation’s ideological sharpness. Its cutting edge had been blunted.

The party leadership passed into the hands of L K Advani. The manner in which Vajpayee had been sidelined left a scar in the minds of many on his side, though he himself did his best not to let his feelings be known to all and sundry. He went into a self-imposed exile, devoting more time to his personal pursuits. Willy-nilly a divide had cropped up in the party, with people talking about the Advani group and the Vajpayee group. Despite a cooling off in the relations between the two leaders, both remained impeccably correct in their behaviour to each other.

But quick change is the nature of politics, and the tides had turned fast. A sudden trauma hit Advani when his name came up in the scandalous Jain Diary, as one of the leaders involved in the hawala racket. It was stunning blow not only for Advani, who suddenly decided to quit the Lok Sabha and declared that he would not fight elections till he had been cleared of the charge, but even more for the BJP which had made him its icon. The party did not know which way to look.

Had it not been for the hawala charge, which of course was eventually chopped, Advani would certainly have been the Sangh Parivar’s choice for the Prime Minister’s post. So unblemished had been Advani’s track record that most people found it hard to believe that he could have wallowed in the muck of corruption like other politicians of easy virtue. The charges were met boldly and yet a certain amount of damage to the leader’s morale had already been done. The impact of such allegations is always greater when they are made against an unlikely man.

The stigma is behind him, and yet with Vajpayee having once become the party’s Prime Minister, Advani had to take second place. That had been his usual position in the party until his sudden rise after the tumultuous Rath Yatra. They were the two top leaders of the party who had complemented each other: while Vajpayee was the charming campaigner and vote-catcher, Advani was the solid organisational man, drafting the party’s important statements and policy papers, overseeing the nuts and bolts of the party at the Centre and in various states. It was not for nothing that while Vajpayee was consistenly a Lok Sabha man, Advani preferred to be in the Upper House. He was not seen to be much of an elections man, except as a poll theorist and manager. He preferred to stay off the pulpit and concentrate on the nuts and bolts of the party, for which he got more time being a Rajya Sabha member.

ADVANI had willy-nilly taken the second position, but his men kept emphasising that he was the “real power” in the government. When a weekly magazine was doing a story on “India’s ten most powerful people” in July 1998, its correspondents talked to a wide range of people in the corridors of power, and they finally decided to put L K Advani ahead of Vajpayee. “Despite not being the official number one,” said the magazine, “Advani’s clout derives from the fierce loyalty of the BJP cadres and the respect of the RSS top brass. A no-nonsense strongman, his stranglehold on the party machinery is legendary.”

Advani was putting his men in key positions, and they were doing their best to undermine the position of Atal Behari Vajpayee. In the late 1980s, there was much talk in political and media circles of a new arrival in the BJP headquarters at Ashok Road. He was described as the party’s new ideologue and an ardent supporter of Advani. Journalists covering BJP affairs were mighty impressed by the ‘jolly good fellow’, originally from the South but fluent in Hindi having lived and studied in Benares. A lean and thin dark man, K N Govindacharya lived a spartan life in a room at the back of the party headquarters, and had become a frequent visitor in various newspaper offices in the capital. He had been a devoted RSS pracharak for many years, and was no stranger to journalists who had covered Jayaprakash Narayan’s movement in Bihar, with which he had been associated. Govindacharya had studied the politics of various states, especially in the cow-belt in great details, and could analyse political developments very clinically without giving the impression of being a hardcore RSS man. All in all, he was considered an asset to the BJP headquarters and had become popular with journalists and political observers interested in understanding the party’s mindset. An additional reason for his clout was his known proximity to the party strongman L K Advani.

Govindacharya, who had been made a general secretary of the party, soon become rather well known, not only because of his cerebral qualities but also for less flattering reasons. At one point, he had got involved in a rather murky controversy because of his alleged affair with the young BJP member of Parliament, Uma Bharati. But that apart, he was known as an aggressive camp-follower of Advani, and a covert critic of Vajpayee, about whom he passed uncomplimentary remarks, of course in private.

Govindacharya’s public remark that the party needed to change its chaal, chehra aur charitra (its ways, face and character) had been widely interpreted as being directed against Vajpayee and his supporters. And then, perhaps in a moment of indiscretion, Govindacharya happened to make certain remarks about Vajpayee to a couple of British High Commission officials, which first got into an RSS journal and was then lifted by other newspapers and magazines, creating quite a furore. In a conversation just a few months before the 1998 Lok Sabha elections, the British officials had asked Govindacharya about the impression that had gained ground that ‘it is Mr Vajpayee who prevails (in the party’s policy matters) in the end?’ Said Govindacharya: “If a loudspeaker and a mask are to be considered the main spokesman of the party line, this kind of view may be taken.”

British officials: Is it true that leaders like Vajpayee and Dr. Joshi (Murti Manohar) are against Kushabhau Thakre’s candidature for party president’s post?

Govindacharya: As far as Mr Atal Behari Vajpayee is concerned, his opinion is not really important.

British officials: What is the source of BJPs inner strength? We’d like to know about the person behind this strength.

Govindacharya: That person is Lai Krishna Advani. Irrespective of who the next president is, Advaniji’s word will be the last word.

Govindacharya, of course, later claimed that his words had been distorted. He maintained that rather than calling Vajpayee the party’s mukhauta (mask), he had called him the party’s mukut (crown). His clarifications did not wash. For one, his views on the two leaders of the party were rather well known, and since he had spoken to the British officials in English, Govindacharya could not possibly have used words like mukhauta and mukut.

In any case, Vajpayee had decided he would not take it lying down. He was on a foreign trip when Govindacharya’s remarks had got into the press, but no sooner he returned than he sent off a cryptic letter to party president Advani: “On returning from my foreign trip I read an interview given by Shri Govindacharya. You must have read it as well. Vijayadashmi greetings to you.” To Govindacharya, he shot off another letter seeking an explanation. Vajpayee was no longer the lonely escapist of the mid-1980s. He had already been the country’s Prime Minister, albeit for 13 days, and he was in no mood to take any nonsense from a greenhorn at the party headquarters. A day later, Vajpayee had remarked at a book release function with cutting irony: “I wonder why I have been invited to speak here when I am only a mask.”

The cracks had come into the open. Advani’s acolytes had found it rather hard to swallow the general public perception on the eve of the Lok Sabha elections that the tide in the party’s electoral prospects was because of the projection of Atal Behari Vajpayee as Prime Minister. Not again, many of them had said, but there was little they could do. A mask or not, Vajpayee was certainly the party’s winning card. This was evident from the various pre-election opinion polls Without Vajpayee as the leader it was even difficult to visualise the alliance which made it possible for the BJP to form a government.

THE first Vajpayee government had been too brief and inconsequential for his detractors to show their hand. But the second time, the Advani-Vajpayee divide even cast its shadow on the bureaucracy. So much so that the Prime Minister was not sure about the credentials—and loyalty —of some of his own officials in the Prime Minister’s Office. Because of this mistrust, the Prime Minister did not even hold a meeting of PMO secretaries. The Prime Minister worked through a handful few like his media advisor, Ashok Tandon, a former journalist of the Press Trust of India, and Brajesh Mishra, a former career diplomat who handles essentially external affairs issues. In the Cabinet, the Prime Minister was closer to allies like George Fernandes than to Advani and Murli Manohar Joshi, who he saw as constantly looking for an opportunity to embarrass the government.

Jayalalitha continued to be his most nagging problem. When her nominee, Sedapatti R Muthaiah, had to quit because of a chargesheet against him, she publicly demanded the resignation of all chargesheeted ministers, including Ram Jethmalani, Ramakrishna Hegde, Murli Manohar Joshi and Uma Bharati. The crisis almost looked like bringing down the government, but the situation was saved by Jaswant Singh who went to Chennai to talk to her. Again, it was the promise of action against the DMK government and of going slow on her cases that brought Jayalalitha around. The Prime Minister continued to be under constant pressure from the lady of Poes Garden, and were it not for a disinterested Congress, she would probably have switched sides already and toppled the Vajpayee government.

There had been several exits from the government: first Muthaiah, then another nominee of Jayalalitha, R K Kumar, ostensibly on health grounds, and some time later Sardar Buta Singh because of his involvement in the Jharkhand Mukti Morcha bribery case. Vajpayee was eager to expand his ministry, but there were so many claimants and so many clashing interests that he kept putting it off. Finally, he fixed a date for it: October 10. The date came and went, without any expansion. Faced with ‘unreasonable demands’ from various constituents of the government, the Prime Minister put it off indefinitely.

Within six months, the Prime Minister’s profile had registered a sharp decline. The only high point his supporters could recall instantly was May 11 when a beaming Vajpayee had announced two nuclear tests at Pokhran. It had certainly taken the world by surprise, and if it brought an instant blast of global criticism, it had also produced a sense of exhilaration and pride among large sections of Indians. The government had clearly been working at it, and thought it would be a dramatic shift from the day-to-day struggle of keeping the coalition afloat. The BJP had always maintained that their government would bring about ‘a new flowering of the nation’, a great resurgence. Instead, the first few months of the Vajpayee’s second government had been marked by the daily antics of one ally or the other throwing their tantrums, pressing their demands, threatening to pull out. Every other week a Vajpayee envoy was rushing to Chennai or Calcutta to massage the egos of the angry prima donnas.

VAJPAYEE was clearly out of sync with what many of his allies were doing. Within some weeks of his becoming the Prime Minister, he visited Mumbai for a day and a half. On the evening of his arrival, Governor, P C Alexander threw a banquet in his honour to which came the State’s top leaders and the city’s elite. At one point during the eveing, an eminent Muslim citizen went up to the Prime Minister and requested that he should make some time for a kavi sammelan in the city. An evening of sher-o- shaeri. “What sher-o-shaeri are you talking about?” Vajpayee said with great annoyance. “When a singer like Ghulam Ali comes to sing in your city, you disrupt his programme and you talk of having sher-o-shaeri?” He said this in the hearing of the top Shiv Sena leaders, but of course they made as though they had heard nothing. But at a press conference the next day, the Prime Minister repeated his annoynance at some of the goings-on in Maharashtra. The elan was clearly slipping, both in Delhi and elsewhere.

Something had to be done fast not only to divert the people’s attention from the ongoing shenanigans of the allies but also to show that here was a government that was different from the others.

Let’s go ahead with some big blasts, they thought. That would retrieve the country’s lost pride and bring the BJP right back into reckoning. There was nothing new about the party’s commitment to a nuclear bomb. It had been the Jan Sangh’s article of faith, and when Indira Gandhi had tested a nuclear device in 1974, Vajpayee had been one of the first opposition leaders to hail her. On this issue at least, there was no divide in the party. Even the normally staid and cautious Lai Krishna Advani had said in an article in the RSS daily, The Motherland, “Only twice in recent years has one witnessed such a mood of national elation. First, when the Indian Army entered Dacca to liberate Bangladesh, and now when India has entered the nuclear club.” On May 11, when the first signal came from Pokhran that it had been ‘done’, tears had welled up in Advani’s eyes. “Buddha had smiled again”, after a gap of 24 years.

A sense of fulfilment showed on Vajpayee’s face as he stood at the podium, specially decked up to look like the one in Clinton’s White House. The statement was brief and terse, which he read out crisply and clinically, as leaders of nuclear nations do on such occasions. Vajpayee had initiated the moves for the country going nuclear even during his first stint, when he had summoned the chief of the Department of Atomic Energy, R Chidambaram to his office. But that time Vajpayee had lasted just 13 days, and his successors were too weak-kneed to order the blasts.

The shock waves from Pokhran-II travelled instantly across the globe, and condemnation had poured in from far and near.

President Bill Clinton was crisp and clinical at his own podium. He was fast in clapping sanctions on India. Even so, India had gone ahead with two more explosions at Pokhran, before declaring that India had now completed the necessary tests and was adopting a voluntary moratorium on further tests. And now that India had entered the nuclear club, it could go on discussing the rights and wrongs of the CTBT till the cows came home. What was done was done, and Indians seemed proud of it, with opinion polls showing nearly 80 per cent endorsement of the tests.

Pakistan, quite expectedly, followed suit, and claimed that it had not been the first to start the race. “Nuclear weapons,” said an editorial in The Economist, “make governments, and their peoples, feel strong and powerful. The feeling is illusory. If India has been taken less seriously in world counsels than it would like to have been, that is not because it has lacked nuclear weapons. It is because it is a country whose governments have so mismanaged its affaris, especially its economy, that it has had little authority with which to underpin its influence. Indians like to think their influence will now grow; criticism will count for little and soon evaporate; they will be great at last. They point to the short-lived boycott of China after the massacre in Tiananmen Square in 1989. Yet they miss the point, the world takes China seriously, however reluctantly, because of its economic might and commercial potential, not because of its military prowess.”

The immediate purpose of the blasts was clearly to re-establish the government’s fast eroding credibility, but this was hardly achieved. After a few days of babel over the explosions, a mix of three-fourths euphoria and one-fourth condemnation, the Vajpayee government was back to business as usual: ministers shuffling between Delhi and Chennai, soothing the frayed tempers of the Poes Garden lady who seemed to be afflicted by a chronic seven- day itch, as it were.

A breaking point was reached in August when she became a little too much even for a patient Vajpayee. She wanted all kinds of things done, immediately. “For three days, in person and over long distance cellular calls,” wrote Swapan Dasgupta, a senior journalist known to be a member of the BJP’s charmed circle, “they listened and negotiated. Jayalalitha’s demands were characteristically immodest. First, she demanded the removal of Enforcement Directorate (ED) chief M K Bezbaruah. It was instantly conceded. She also wanted her own nominee as Bezbaruah’s successor, quite forgetting the Supreme Court’s stipulation on the procedure of appointment. The government pleaded helplessness. Jayalalitha sulked. Second, she demanded the replacement of Revenue Secretary N K Singh with Banking Secretary C M Vasudevan. Vajpayee met her half way. Singh was shifted to the Prime Minister’s Office and Javed Chaudhary, a former ED chief, replaced him in North Block. “Who is he?” asked Jayalalitha. “Replace him.” “We will try,” replied the interlocutors. “You don’t have to try, you have to do it,” she retorted menacingly.” Always egging her on was Dr. Swamy. The more imperious she was, the more he grinned.

VAJPAYEE was unable even to fill up the vacancies in his Cabinet, far less expand it. He was becoming more and more a prisoner of circumstances, of contrary forces pulling him apart. Basically a loner and pessimist at heart, he was going inwards, speaking less, sleeping less, smiling less. It wasn’t the same Vajpayee, everyone started saying, and the air was rife with all kinds of speculations about his health taking a downward dip. Unlike some of his predecessors who had been on the television almost all the time, Vajpayee had made himself much scarcer, which was really a wise thing to do for there can be no greater danger to a leader’s public image than over-exposure on the television. People can get so tired and bored, as had happened in the case of Inder Kumar Gujral, without his realising it.

But Vajpayee was now harming himself by under-exposure. It seemed he had withdrawn into a cell, leaving things to happen as they wished: prices of onion and other essential commodities to go up and up like a beanstalk, the criminal mafia to have the run of the cities, the satraps in the various states to act as they pleased. Innocent nuns were being raped in Madhya Pradesh by hoodlums associated with various fronts of the Sangh Parivar; goons of the Bajrang Dal were raiding colleges in Ahmedabad and other parts of Gujarat to ‘teach lessons’ to young women who dared to dress up “like Madonnas”, volunteers of the Dal were keeping tab on inter-caste marriages in cities and threatening anyone from the minority communities planning to marry a Hindu boy or girl with dire consequences. Vajpayee could have been in tune with none of this and yet he was helpless, just watching the swift decline in his government’s image.

He had become a creature of circumstances, caught up in the cross-fire of contrary forces. The latest round of expansion had to be put off because they were too many demands from the allies. Jayalalitha wanted four ministers and the removal of V Ramamurthy from the Petroleum Ministry. The Prime Minister said he could not accommodate so many ministers and postponed the expansion. But again the party embarrassed him. Even while officials of the PMO were telling everyone that no expansion was on, BJP vice-president Krishan Lal Sharma announced that the expansion would be held. A day later, the PMO had to officially deny the BJP headquarter’s version.

The postponement of the Cabinet expansion meant that Jaswant Singh again remained out, so did Pramod Mahajan who, though very close to the Prime Minister, was ousted from every conceivable party body including the parliamentary board and the central election committee. At one time, the high-profile spokesman of the Prime Minister, Mahajan was quietly removed once he became too important. Some said his downfall came about because he had become too close to Ranjan Bhattacharya, the Prime Minister’s son-in-law. The latest was that Mahajan was lobbying for the lucrative Communications Ministry, which was vacated by the chargesheeted Buta Singh. But former Delhi chief minister Sahib Singh Verma also wanted the post.

Vajpayee-Advani relations had clearly hit a new low, with the knowing ones openly talking about the tug-of-war even inside the Prime Minister’s Office, with the result that Vajpayee’s dependence had shrunk to just a few close bureaucrats and personal advisers. “The Prime Minister is constantly suspicious that his No.2 is conspiring against him,” said a journalist who keeps a close tab on the Prime Minister’s Office. Socially, the two leaders did not even meet. The Prime Minister had invited him for his granddaughter’s birthday on Diwali eve but he did not go. During the Prime Minister’s absence, Advani always chaired the Cabinet meetings, but constantly went against the Prime Minister’s wishes, particularly on the Bihar issue.

“Who is in charge in Delhi?” people were asking. If the Prime Minister looked unhappy, saying he was much better off delivering a speech in Parliament as an opposition leader, even unhappier were the hard-core leaders of the BJP, the Sangh Parivar and its various front organisations. They did not consider this their government, for all their main objectives had been ‘sacrificed’ in favour of an agenda they did not agree with. “Wait and watch what a real BJP government can do,” they boasted, little realising that such a government could well remain a pipe-dream.

THE biggest reverses were still to come: a big snub by the electorate in the assembly elections, with even their long time bastions like Delhi and Rajasthan slipping away from their grasp. No doubt the Vajpayee-baiters would use the reverses as a stick to beat the Prime Minister. But there was little he could do. Hopes of giving the country an ‘able and stable’ government had long wilted.

On November 6, 1998, a harried Prime Minister Vajpayee arrived in Bombay to give away some prizes. It looked like a virtual red-alert, with truck loads of policemen pouring into the Chavan auditorium, almost a hundred policemen for every citizen present. The city’s traffic was topsy-turvy, as though some enemy forces had landed. And yet Vajpayee’s image-makers were claiming this was one of the most ‘open’ governments that the country had had. In his speech, the Prime Minister urged the Chief Minister to do something fast about the worsening crime situation in the great city of Mumbai, and I wondered if he had realised what 99 out of the city’s 100 policemen were usually engaged in. Perhaps he did, for his sensibilities are still more of a poet than of a politician in power, which is why he is more pained and oppressed. “It was much better being in the Opposition,” he told the audience. He could at least speak then; he can’t now.

Excerpted from Prime Ministers: Nehru to Vajpayee by Janardan Thakur, Eeshwar Prakashan, New Delhi