IT was a taunt and better prospects of growth and emoluments that brought Kamal Krishna Sinha into Indian Administrative Service (IAS). Otherwise Sinha, son of RKP Sinha, a provincial civil servant (PCS) in Bihar Capital, and Phool Kumari Devi, a housewife, was more than content teaching students of Regional Institute of Technology (RIT) in Jamshedpur. He had got into teaching at the age of 18 after completing his post-graduation in Chemistry from Patna University in 1958. To add gravitas to his young outlook, he then kept a beard.

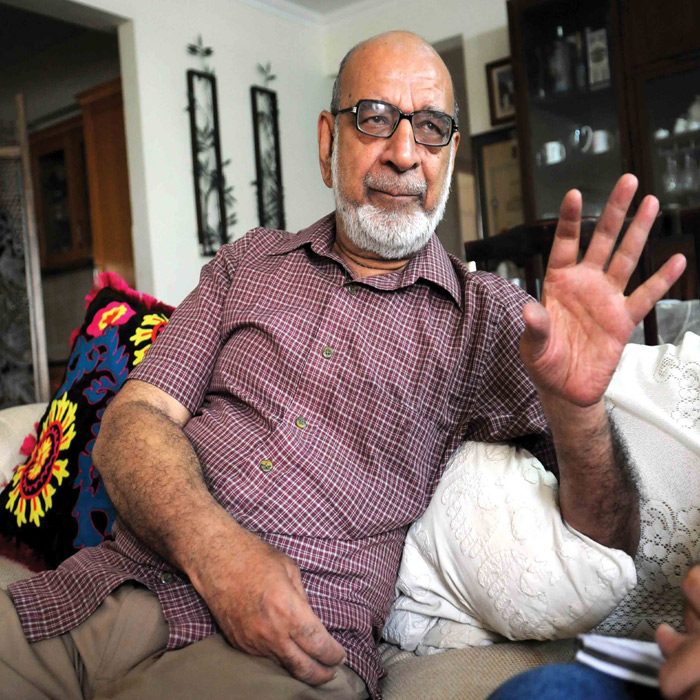

“Mere ko kisi close ne kaha UPSC exam se darte ho (Somebody close to me said that I found the exam daunting). Moreover, an IAS’ starting basic had just been hiked to Rs. 400 per month, double than a lecturer’s starting basic, and the process of getting higher responsibility and emoluments was much quicker there”, Sinha, now in his 80th year (78th officially), recalls.

Civil Services was considered a great status symbol in Bihar then. He opted for British History, Law and Constitutional History as subjects and appeared for the exam in 1962. On June 3, 1963, he joined Lal Bahadur Shastri National Academy of Administration (LBSNAA) as a probationer.

On passing, he was allotted Assam cadre and appointed as Assistant Commissioner (in Assam, the Deputy Collector or District Magistrate was called District Commissioner) in Dibrugarh, then a part of Lakhimpur district. He got a bird’s view in treasury, judiciary, fishery, rural governance, police stations and sundry other departments. Subsequently, he cleared a language exam in Assamese and Bengali to get his first increment of Rs. 100.

In 1967, immediately after his marriage with Neelam, a teacher, he was appointed Additional District Commissioner (ADM) in Mizo Hills, then a district of Assam, which was battling insurgency.

Sinha recollects there would be a daily curfew in the district after 6 pm and he would be allowed entry into own his official residence with a password. Besides, the district administration had teething problems in getting along with the army officers. An army officer in fact once called Sinha ‘God’s only creation’, an idiom used to mock IAS officers.

But subsequently, the relations between the administration and army establishment got better. So much so that when a three mile stretch of Silchar-Aizawl road caved in bringing to a halt transportation of ration to the district, army officers helped the civil administration in tackling the problem. “We could look after our 500,000 people because army agreed to pass on a part of its ration quota. The army officers even supplied foods for children and cartons of Panama cigarettes to be sold from ration shops”, he remembers.

The district administration and the army subsequently divided villages into groups and introduced an identity system for them. This was a unique experience to isolate Mizo insurgents. Sinha says during his little less than three-year long tenure, they greatly succeeded in snuffing out militancy from their district.

During 1971 Indo-Pak war, Sinha was posted as District Commissioner in Garo Hills, an Indian district that shares boundary with Bangladesh. Apart from handling its own population of around 450,000, the district catered to eight lakh Bangladeshi refugees. Many refugees were settled along 28 km long Tura-Dalu road.

There was a major emergency after a bridge built on a river near the border got washed away in flood. This stopped ration supply to refugees. Sinha was told by an engineer that it would take at least 12 days to repair the bridge. When the former asked him to do it in one day, he asked for 3,000 labourers. District administration put 3000 refugees into work and the bridge was made operational in one day.

In 1973-74 when Sinha was Secretary (Agriculture) in the state, a major initiate was taken by the state to stabilise production of potato seed in Meghalaya. Meghalaya, then a district of Assam, supplied seeds not only to parts of northeast but also Bangladesh. But the seed supply was erratic. Agriculture department brought together a cooperative society of 3000 potato farmers. They were given loans. The seed production stabilised but the loans were never repaid. Sinha calls the mission half successful – successful reproduction wise but failure financially.

During the same tenure, Sinha also launched a scheme on dairy cooperatives to popularise cow milk among Khasi tribes. Khasis in those days did not like cow milk and had no cowherds. Instead of milk, they would feed banana seed to their children. Agriculture ministry in collaboration with an NGO, MYRADA (Mysore Resettlement & Development Agency), set up a dairy cooperative society and provided loans to villagers for buying cows. At the end of the project, Sinha points out, 48 villagers in Khasi hills took to dairy farming and they paid off all their loans.

From 1979 to 1981, Sinha was Secretary to LP Singh who was Governor to five northeast states. He says he wrote so many research papers for the Governor that had he been into academics, he would have been awarded 4-5 PhDs.

In September 1988, Sinha was moved to centre and became Joint Secretary (Northeast) in the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA). As JS, one of his first steps was to oppose extension of District Council to Manipur, a decision approved by the Union Cabinet. His seniors warned him against it. They thought opposition to a cabinet decision could get him on the wrong side of the powers-that-be. Sinha argued that the extension of the council could increase insurgency in the state. He took the issue to the then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi and was successful in getting it reversed.

During his tenure as JS (Northeast), Sinha along with his colleagues from other ministries was instrumental in settling the issues of language, citizenship and reservation in Sikkim, a new state which merged into India in 1974.

There was a demand for inclusion of Gorkhali language in 8th schedule of the Constitution. There was also a demand for reservation for certain classes of people including heads of two Mathas (religious institutes) in the state assembly. There were demands that the territorial formula of Goa and Puducherry be extended to Sikkim to decide citizenship. He argued against it before Committee of Petitions on the grounds that Sikkim already had a citizenship register. They took about two years in settling the issue. In January 1990, Sinha was appointed JS (Kashmir) in the home ministry and told to create a division for the terrorism-afflicted state.

Sinha retired on January 31, 1998 as Chairman, Food Corporation of India (FCI). None of his children—two daughters, Taru and Gopa, and a son, Manu—are into civil services. Taru and Gopa are US-based doctor and architect, respectively, while Manu is an Engineer. In fact, he points out that from his batch of 89 IAS (1963 batch), only children of less than a half a dozen have got into civil services. The rest is settled in private jobs.

Sinha, a recipient of Padma Shri award, has a tinge of regret that the government never allowed him and his father to correct his date of birth. It so happened that his grandfather, who took him to school for admission, wrongly quoted January 2, 1940 as his date of birth, two and a half years more than the actual date of birth (October 11, 1937).

His father tried to set it right at the time of his college admission but a medical board constituted for the purpose of determining his real age, overruled him and approved the wrong age.

As told to Narendra Kaushik