- Cover Story

- Governance

- Globe Scan

- Corruption

- State Scan

- Talk Time

- Cover Story

- Governance

- Globe Scan

- Corruption

- State Scan

- Talk Time

Recent Posts

© Copyright 2007 - 2023 Gfiles India. All rights reserved powered by Creative Web INC.Haryana 51 YearsHaryana’s political journey

The land of Lals for the first four decades of its existence, has come a long way with each of its 10 chief ministers contributing in some way in the long journey

Narendra KaushikDecember 10, 201711 Mins read2.1k Views

Written by Narendra Kaushik

Written by Narendra Kaushik

WHEN Haryana, or what was then known as South Punjab, was made a separate State on November 1, 1966, it hardly had anything going for it. The basic amenities—drinking water, electricity and roads—were scarce.

Over 80 per cent of its 6,841 villages were living in the dark. They had no access to potable drinking water and still drew their intake out of wells. The connectivity was poor with cycle, tonga and bullock cart being used for ferrying people. The number of people owning tractors in villages was rare. In cities, people travelled in private buses.

Southern Haryana cultivated and irrigated its farms from wells with the help of camels while the rest of the State did the same with pairs of oxen. There were no canals, particularly in the arid part of the State.

Many people in villages, particularly the ones belonging to weaker sections, still lived in mud houses. Many of them rolled their chapatis from coarse grains like millet and corn. Cattle rearing was a co-vocation with agriculture. People grew millet, sorghum, wheat, corn, sugarcane, gram and cotton etc.

Entertainment was limited to listening to radio, folk dramas and songs like saang, alha and bhajan, ragini and deru (kind of a drum). Screening of films in villages by State’s culture department and occasional watching of films in talkies in cities were other options.

Mortality was very high with no healthcare available for infants and women during delivery. The raison d’être for demanding the State was alleged discrimination between North Punjab and South Punjab (now Haryana) and dominance of Punjabi culture.

Caste was entrenched in Haryanavis’ psyche then also. Jat politicians like Chaudhary Devi Lal and Sher Singh were at the forefront of agitation for Haryana. According to Bhim S Dahiya’s book, ‘Power Politics in Haryana: A View from the Bridge’, though castes other than Jats were not against creation of the new State, they ‘remained aloof from the movement’.

Manohar-Lal-Khattar Logically, Devi Lal, then a Congressman, should have taken the first shot at ruling the new State. Instead, Bhagwat Dayal Sharma, who presided over Punjab State Congress at the time, wrested the honour. Ironically, Sharma was against the division of Punjab. He feared domination by Jats in the new State. He managed to become the first Chief Minister due to his closeness to central Congress leaders.

Sharma became a pioneer in nourishing Jat-non Jat template of politics in Haryana. In 1962, Sharma fought a bitter battle in Jhajjar constituency (then part of Punjab assembly) against Professor Shamsher Singh. The supporters of the two were vertically divided on caste lines and were in no mood to concede defeat.

Singh had the strong backing of Jats while Sharma looked for consolidation of all other castes. It was feared that followers of the losing candidate might resort to violence. Singh, who ultimately lost to Sharma, averted the clash by lying to his Jat followers that he had won the election and they should head to homes in victory processions.

With the ascent of Sharma, surprise, contradictions and caste and conspiracy made an entry into Haryana polity. In the first assembly elections in Haryana in 1967, Sharma was forced to change his seat from Jhajjar to Yamunanagar because people in Jhajjar, particularly the Jats, were thirsting for revenge.

SHARMA continued to be the CM after constitution of a new assembly on March 17, 1967, though his candidate for assembly speaker Dayakishan lost the election. Sharma’s tenure of less than five months before the first State elections became controversial when he declared in a public meeting at a grain market in Rohtak, “This time around I will not let Chaudharies have a say. I will ensure their canes are suspended on spikes.” This was as direct a jibe against the Jats as could be.

Sharma, who later represented Karnal in the Lok Sabha and also served as governor of Madhya Pradesh, is also remembered for advising Haryanvis to get used to eating ‘mota anaaj’ (millet and corn). Haryana in those days mostly grew these and only became a major producer of wheat and rice after the green revolution in the 1970s.

(left to right) Devi Lal, Chandra Sekhar, VP Singh On March 24, 1967, Rao Birendra Singh, the scion of royal family in Rewari and head of Vishal Haryana Party (first State party in Haryana), replaced Sharma as the Chief Minister. Adopted son of Rao Balbir Singh, the titular head of Rewari, Birendra Singh was selected for IPS (Indian Police Service) in 1949-50 but did not join. Being well-educated, Singh had a mind of his own and is remembered as a strong administrator.

But his area of influence was largely confined to the Ahir belt (Rewari and surrounding areas) and he did everything to nurture it. Moreover, he was Chief Minister for barely seven months and nine days. On November 2, 1967, the government of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi dismissed his government and imposed President’s rule on the basis of a report from the Governor whereby stability of his government was questioned.

Logically, Devi Lal, then a Congressman, should have taken the first shot at ruling the new State. Instead, Bhagwat Dayal Sharma, who presided over Punjab State Congress at the time, wrested the honour

Rao Birendra Singh was the one who coined the term ‘Aya Ram Gaya Ram’ which became synonymous with defections across the country. It so happened that Gaya Lal, a Congress MLA from Hasanpur (Palwal), changed parties thrice in a fortnight in 1967. He quit Congress to join United Front (Janata Party) and subsequently returned to the Congress. Singh introduced Gaya Lal to press in Chandigarh saying ‘Gaya Ram’ is now ‘Aya Ram’. But shortly afterwards Gaya Ram switched over to the United Front again.

In May 1968, fresh elections were held for Haryana assembly and Bansi Lal, a second-time MLA and favourite of Indira Gandhi, became the Chief Minister. Lal contributed majorly to construction of approach roads, canals and electrification, irrigation and drinking water in the State.

Lal, an honest but arrogant and stubborn politician, set a target for his electricity staff and made sure that 5,500 villages (1,250 villages were already electrified when he took over) were electrified within a short span of time. During this he would move around at night and constantly take updates from electricity department’s superintending engineers and other staff.

Lal, a former President of bar association in Bhiwani, took the private transport (buses) under State’ wings, created Haryana Roadways and provided connectivity. During his third tenure in 1996, his government granted licenses to cooperatives owning buses to ply within the rural sector.

Lal took canals over sand mounds in Mahendragarh, Narnaul and Bhiwani where nobody could imagine them. For this, he sent an engineer to a foreign country to study lift irrigation and then issued him huge funds (around `80 crore) for the job. He generously allocated backward area grants.

Lal was a man of his word and even than had dictatorial tendencies. After a tussle with Punjab over some road passing through Punjab’s territory, he got a bridge constructed over Ghaggar river and road laid in a record time to connect Panchkula with Shahabad (Kurukshetra) circumventing Punjab’s territory. Voters in the State apparently did not mind his dictatorial behaviour and reelected his government in 1972.

Lal served as the state CM till December 1975 when Indira Gandhi decided to make him Defence Minister of the country. He had a say in choosing Banarsi Das Gupta as his replacement. Though Gupta served as CM for a year and five months, he could never grow out of Lal’s shadow.

His mentor Lal himself lost much of his sheen by implementing agenda of Sanjay Gandhi, Indira Gandhi’s younger son. He allegedly cut off power supply to newspaper offices and closed down courts. Lal has been the longest serving CM of Haryana till date.

During Janata Party wave in 1977, Devi Lal, a former head of Punjab State Congress and a popular farmer leader, stormed into power in Haryana. Devi Lal did not have Bansi Lal’s vision and chutzpah but made up for it by inflating his social base.

UNLIKE Bansi Lal, a development man, Devi Lal proved to be a populist. He initiated number of social welfare measures to extend his popularity. His old age pension was a first in the entire country. He also rolled out pension for handicapped and widows. He initiated a work-for-foodgrains programme for the poor as well. His government constructed Harijan chaupals and initiated a rural industry scheme under which not only did the government give subsidy for setting up the industry but also bought the entire production. The industry scheme proved to be a failure.

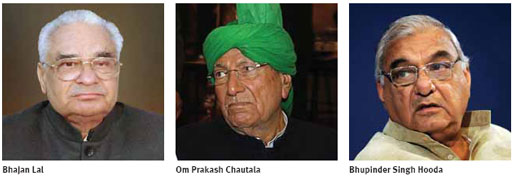

(left to right) Ch. Bhajan Lal, Om Parkash Chautala and Bansi Lal Devi Lal would visit villages, eat food, drink lassi and smoke hookah with villagers. He always made it a point to fulfill commitments made in such gatherings. During his second term as the CM, Devi Lal waived loans up to `10,000 issued to farmers, landless cultivators, artisans and weavers by State-run banks. He migrated to the Centre to be Prime Minister VP Singh’s deputy on July 10, 1990, after handing over reins to his son Omprakash Chautala.

But Devi Lal obviously failed to keep his herd of MLAs together during his first term. On January 28, 1979, Bhajan Lal, the harbinger of wholesale defections in the country, struck and moved away to Congress with the majority of Janata Party MLAs, thus bringing an end to Devi Lal’s first tenure as chief minister.

Bhajan Lal was chief minister till June 4, 1986, and had returned to rule after elections in on the strength of consolidation of non-Jat voters in his favour. He also served as CM from July 23, 1991 to May 9, 1996. Lal pushed for large industry in the state. It was under his stewardship that Maruti took wings and industrial hubs like Faridabad and Manesar came into being.

His tenure, however, is remembered more for institutionalisation of petty corruption in the State. Lal raised a banner of revolt against Congress high command in March 2005 when it backed Bhupinder Singh Hooda for Chief Ministership but fell in line after Hooda made his first son, Chander Mohan, his deputy.

ON May 11, 1996, Bansi Lal rode back into power on the back of his coalition with Bharatiya Janata Party and promise of total prohibition. The latter proved to be his biggest undoing. His younger son, Surender Singh, allegedly patronised liquor smuggling in the State. Total prohibition dug a hole into the State exchequer leaving no money for development works. In June 1999, the 11-member BJP withdrew support from the government. Bansi Lal’s sterling performance during the first half of his career is diminished by his role in emergency and failure during the second term.

Chautala, presently incarcerated over corruption in recruitment of junior teachers during his tenure, has been Chief Minister of Haryana for record four times. He extended welfare schemes announced by his father and released huge grants to village panchayats.

Unlike Bansi Lal, a development man, Devi Lal proved to be a populist. He initiated number of social welfare measures to extend his popularity. His old age pension was a first in the entire country. He also rolled out pension for handicapped and widows

But he is likely to be remembered for his highhandedness with bureaucrats and MLAs (there are stories that his younger son Abhay would beat his party MLAs) and appointment of dummy Chief Ministers, Hukum Singh and Banarasi Das Gupta.

Singh warmed the chair for Chautala from July 17, 1990 to March 21, 1991 in the wake of killing of voters at a polling booth in Meham where Chautala was pit against independent Anand Singh Dangi, while Gupta filled in for him for 52 days in 1990 after killing of Amir Singh, an independent candidate in the same constituency. The four-time CM holds the dubious distinction of having completed only one tenure (2005). Earlier this year, there was a controversy on whether Chautala sat for 10th or 12th examination under National Institute of Open Schooling (NIOS) in Tihar jail.

Bhupender Singh Hooda was chosen as Chief Minister in 2005 due to his clean image and was supposed to provide honest government. But during his two terms (2005-2009 and 2009-2013) he squashed that hope by taking too much interest in real estate and building a constituency for himself and his son. Hooda focused on shining Rohtak, his native district, and Sonepat and Jhajjar, its adjacent places. Thanks to his efforts, Rohtak has four-lane roads connecting it to Jhajjar, Bhiwani and Delhi. It is now a city of stadia, flyovers and industry, educational institutes and shopping malls.

Hooda neglected the rest of the State. In 2009, he returned to power largely due to Congress’ great performance in these three districts and support from Kuldeep Bishnoi’s Haryana Janhit Party (HJP).

Hooda has been under a cloud since last year when a panel set up under Justice SN Dhingra claimed that laws were flouted in granting land licences in Gurugram under his regime. Robert Vadra, son-in-law of Congress chief Sonia Gandhi, was one of the alleged beneficiaries of this. There are reports that the Congress high command may keep Hooda in the doghouse to save Vadra.

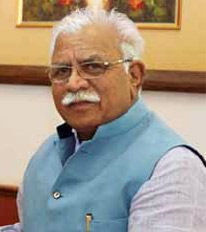

Manohar Lal Khattar, the present incumbent serving since October 2014, holds true the French saying ‘More things change the more they stay the same’. The first Punjabi Chief Minister of the State is facing an allegation that he has pit 35 biradaris (castes) against Jats, the dominant caste that plays a decisive role in 30 out of the 90 assembly seats.

There are murmurs in the State that Khattar first allowed Jats to go on a rampage in February this year over reservation and then silently encouraged other castes to consolidate against the warrior caste. The upcoming assembly elections in the state in 2019 will not just be a test for Khattar but also the State electorate. It is to be seen whether the voters will reject Khattar’s honesty (even veteran Congressmen vouch for his integrity) for a Chief Minister who can get things done and who has a social connect.

In May 1968, fresh elections were held for Haryana assembly and Bansi Lal, a second-time MLA and favourite of Indira Gandhi, became the Chief Minister. Lal contributed majorly to construction of approach roads, canals and electrification, irrigation and drinking water in the State

Khattar, a chronic bachelor like Vajpayee and other Sangh office bearers, keeps off his family. Even his critics admit that he has made a major attempt to check corruption in jobs by reducing interview marks. People count Haryana Public Service Commission (HPSC) among the departments cleaned. He has put in place a system for transfer and postings. He has also decided that he would only recruit engineers from among GATE (Graduate Aptitude Test in Engineering) qualifiers.

Khattar has also purged public distribution system of bogus ration cards. His drawback is he does not even listen to his party workers, has made no effort to connect with people and is found to be indecisive when a crisis triggers. A big example of his indecisiveness was the violence that broke out during Jat agitation for quota in February this year and after arrest of Dera Sachha Sauda head Gurmeet Ram Rahim last month.

There is also a fear that Khattar’s attempt to enforce RSS agenda of Gita and cow may not win him any voters in the State where the only culture is believed to be agriculture.

OVER the years, Haryana has made some rapid strides in development with each of its 10 Chief Ministers having contributed something or the other. Today, along with Punjab and Tamil Nadu, the state is considered to be the rice bowl of the country. It has greatly worked on improving sports infrastructure and facilities, particularly in wrestling and kabbadi where it has had dominance. Now you have stadia, coaches and other paraphernalia available after every few kilometres. The State has appointed coaches even in village schools. Suddenly, every other girl in the State wishes to be a Sakshi Malik and a Gita Phogat.

Haryana is probably the only State in the country where inter-village connectivity has been given a big thrust. Another area where the State has done remarkably well is in girls’ education. It has travelled long distance from being a State notorious for female foeticide to a State where girls outnumber boys in higher education in major universities. Chautala created clean green spaces in the name of his father. You have Tau Devi Lal Parks in almost every big city of the State. However, despite having cut down its losses in transmission and distribution, power cuts are still a norm particularly in the rural sector.

Recent Posts

Related Articles

Haryana 51 YearsHaryana – 50 years and beyond

Written by MC Gupta ON November 1, 2016, a gala event was organised...

ByMC GuptaDecember 10, 2017Haryana 51 YearsA Study in Leadership

Written by SK Misra I was Deputy Commissioner Hissar when Haryana was formed...

BySK MisraDecember 10, 2017Haryana 51 YearsLals of Haryana

Written by Shubhabrata Bhattacharya NOTWITHSTANDING that Chaudhary Devi Lal’s ambition to be the...

ByShubhabrata BhattacharyaDecember 10, 2017Haryana 51 Years‘My strength was that I never sought postings’

Written by Vishnu Bhagwan I was named by my mother, who was very...

ByVishnu BhagwanDecember 10, 2017 - Governance

- Governance