Intending to replace 29 central labour laws, between 2019 and 2020 the central government rushed Four Labour Codes (FLC) through Parliament claiming that they would be a game-changer for the Prime Minister’s flagship Make-in-India scheme and bring a paradigm shift in industrial relations, thereby attracting manufacturing at truly global scales. Now, more than five years later, they have suddenly been notified. A closer scrutiny of some of the important changes that have been brought about reveals why these changes are unlikely to be welcomed by either industry or the labour unions. In fact, it could lead to further erosion of trust between them and degrade our ability to skill our workforce to meet the new challenges of a rapidly changing world.

Contract labour

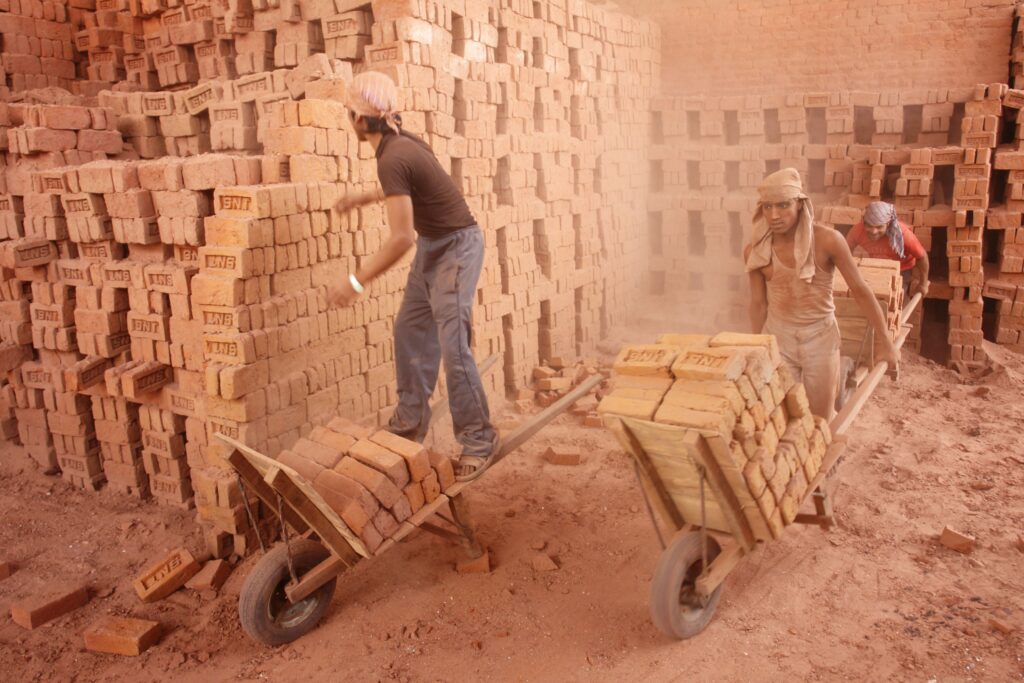

By far the largest segment of our work force is employed as contract labour. They are also the most exploited. Naturally, they frequently raise disputes seeking direct employment with their principal employers so that they can secure better conditions of service, and, more importantly, can get some measure of job security. Employers on the other hand do not want to employ many workers on their direct rolls because they could unionise and seek better emoluments, and more importantly, would find it difficult to retrench them or close their enterprise should the need arise. Even taking disciplinary action against individual employees is a very difficult process. Consequently, employers engage supervisors and legal advisors to keep legal challenges by contract labour at bay or to ensure that they are not successful, often through lengthy litigation. Consequently, if we are to materially impact our labour laws, this is where we ought to start and the main focus ought to be to make the engagement of contract labour mostly unnecessary. This can be done only by enabling employers to engage workers on fair terms while not placing unreasonable restrictions on them on the manner in which they choose to conduct their business. However, the FLC make no such effort. Rather, they further marginalise workers by making the engagement of contract labour easier.

Contract labour is dealt with under Part I of Chapter XI of the Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions Code, 2020 (OSH Code) consisting of Sections 45-58. The relevant definitions are of “contractor” [S 2(f)], “contract labour” [S2 (m)] and “core activity of an establishment” [S 2(p)].

The expressions “contractor” and “contract labour” were also defined under the Contract Labour (Regulation and Abolition) Act [CL Act] but there are new definitions under the OSH Code. A comparison shows that the expression “as mere human resource” has been added to the definition of “contractor” and the exclusion of “a worker (other than part time employee) who is regularly employed by the contractor for any activity of his establishment…” is new to the definition of “contract labour”.

Furthermore, Section 45(1) of the OSH Code takes the threshold for the applicability of these provisions (from 20 under the CL Act) to 50, and only for “manpower supply” contracts. Thus, all establishments would be permitted to employ, without supervision, up to 49 contract labour for “manpower supply”, and unlimited numbers if they are not for “manpower supply”. The term “manpower supply” is also consistent with the term “as mere human resource” used in the definition of “contractor”. (The expression “undertakes to produce a given result for the establishment, other than a mere supply of goods or articles of manufacture to such establishment, through contract labour” in the definition of “contractor” under the CL Act was also intended to convey a similar meaning but this has become more explicit now.) Such establishments may also engage unlicensed contractors, and contractors who are not merely supplying “manpower” or “mere human resource” need not even obtain a license.

In a sense, this was always the case, and not every contract for goods or services was a contract for contract labour and parties often did not apply for registrations / licenses for such contracts. However, who determines whether a service is a mere “manpower supply” or “mere human resource” supply? Thus, the contractors and the establishments will determine in their own wisdom and fight it out in Court if a question were to later be raised. Meanwhile, they will use innovative language to try to make a contract not for a mere “manpower” or “mere human resource” supply. However, this was also the case so far. So, what is different now?

No licence needed

Section 57 now provides employers with three lines of defence against obtaining a license.

The core activity test

Section 57 of the OSH Code prohibits the “employment of contract labour in core activities of any establishment”, thereby adopting the Andhra Pradesh model, and replacing the former regime whereby establishments were required to satisfy the four tests prescribed by Section 10 of the CL Act.

Section 2(p) defines the expression “core activity of an establishment” as expressly excluding several operations. Consequently, such expressly excluded operations can never be part of the core activity of any establishment unless the establishment is itself “set up for such activity”. These exclusions were not present under the CL Act and the question whether contract labour should be abolished in any operation whatsoever was considered in the facts of each case.

The fact that contractors’ establishments that are set up to provide such services to others would not fall under these exclusions does not mean very much because contractors normally hire people specific to contracts, and they pay them only minimum wage and benefits only to the extent they cannot avoid them.

While it may be argued that it is good to provide clarity in the law about what operations would be permitted through contract labour, but doing this without a wider consensus with the unions while raising the threshold for permitting contract labour without obtaining licenses is likely to cause trouble. The fact that contractors’ establishments that are set up to provide such services to others would not fall under these exclusions does not mean very much because contractors normally hire people specific to contracts, and they pay them only minimum wage and benefits only to the extent they cannot avoid them.

Problems with some exclusions under Section 2(p)

Some of the exclusions under this section pose difficulties. For instance, “(i) sanitation works, including sweeping, cleaning, dusting and collection and disposal of all kinds of waste.” “(ii) watch and ward services including security services” and “(ix) housekeeping and laundry services, and other like activities, where these are in nature of support services of an establishment.”

Consider S.O.No. 779(E) dated 9.12.1976 whereby the Central Government had prohibited the employment of contract labour “For sweeping, cleaning, dusting and watching of building owned or occupied by the establishments in respect of which the Central Government is the appropriate Government under the Contract Labour (Regulation and Abolition) Act, 1970. This notification however does not apply to outside cleaning and other maintenance of multi-storeyed building where such cleaning or maintenance cannot be carried out except with specialised experience.” Would such establishments now be permitted to engage contract labour for all such services? Would they be able to retrench those who were regularised in the past and recruit contract labour now? The Code is silent. If they do, it will breed resentment, even disputes.

Statutory canteens

There is a large body of decided case law whereby contract labour in statutory canteens (where a statute such as the Factories Act mandated a canteen in a factory, or a university had residential facilities and hence had to provide a canteen or mess) were required to be regularised in service. The fact that “canteen and catering services” has been defined to “not be considered as essential or necessary activity, if the establishment is not set up for such activity” seems to indicate an intention to also permit such activity in such establishments through contract labour. Now fresh litigation will arise on whether such canteens should get the same treatment that statutory canteens received under the existing provisions or if a factory would be held to have been set up only for the manufacturing of its end product and not for the incidental provision of “canteen and catering services” to those working therein (even though the factory is required by law to provide a canteen).

Matters on which Section 2(p) is silent

Even on matters that the definition under Section 2(p) is silent an establishment that employs more than 49 contract labour could take the position that certain jobs (that really are for the supply of “mere human resource” / “manpower”) are not part of their “core activities” and hence they could engage unlimited number of contract labour for such purposes. Since nothing under the Code obliges them to engage only licensed contractors, they could engage multiple unlicensed contractors and employ any number of people in these jobs. Their view would be tested only if an “aggrieved party” raises such a question or in the rare case where the Government suo motu refers it for adjudication (Section 57).

Obviously then, except for a very few core areas of work, all establishments would be tempted to take the position that their remaining operations are not part of their “core activities” and hence not prohibited. For instance, a factory manufacturing engineering tools might claim that only the workers engaged on the lathe machines are performing “core activities”, not those who are transporting the materials even inside the factory, or those performing secretarial work. An enterprise developing software could take the position that only the coders engaged by them are performing “core activities” and contract out all supporting jobs (receptionists, peons, support staff). This would be the second line of defence.

Engaging contractors in core activities under the proviso

Even in cases where the establishment is engaging contractors for its core activities, it can take the position that it is entitled in its own judgment to the benefit of sub-clauses (a) [“the normal functioning of the establishment is such that the activity is ordinarily done through contractor”] or (b) [“the activities are such that they do not require full time workers for the major portion of the working hours in a day or for longer periods, as the case may be”] to the proviso and thus to engage contract labour. This would be the third line of defence for not obtaining a license.

What is meant by “the major portion of the working hours in a day or for longer periods, as the case may be”? How much period would amount to “the major portion of the working hours in a day”? Why further confuse the issue with the phrase “or for longer periods”? At least a clear guidance should have been given for, now the Courts would have to consider and provide it, and which will take enormous time and expense before it is taken as settled.

What if an establishment had engaged only 15 contract labour previously for such jobs (and hence nobody ever examined the question whether the engagement of contract labour in such work be abolished)? Would they now be permitted to employ 70?

Why is the past practice of an establishment a relevant consideration to determine whether it should be given this exemption? What was considered for the abolition of contract labour under Section 10 of the CL Act was “whether it is done ordinarily through regular workmen in that establishment or an establishment similar thereto”.

Now, one of the factors to be considered under the proviso to Section 57 is whether “the normal functioning of the establishment is such that the activity is ordinarily done through contractor”. As noted earlier, this expression would come into play only after it has been determined that an activity is a “core activity”. Therefore, the effect of this provision is that the establishment could be allowed to engage contract labour in a “core activity” merely because it has historically engaged contract labour to carry it out!

What if an establishment had engaged only 15 contract labour previously for such jobs (and hence nobody ever examined the question whether the engagement of contract labour in such work be abolished)? Would they now be permitted to employ 70? What if an establishment had engaged 30 contract labour previously for such jobs and the question whether the engagement of contract labour in such work be abolished was never considered because it was never raised? Would they now be able to carry on such activity with an unlimited number of people in such work even though they are otherwise “core activities”?

And what about an establishment that is newly set up and operates in the same field? Why should that establishment not receive similar treatment (as it would have under the CL Act)? Hence, this provision might face a challenge also on the ground that it treats equals unequally. Indeed, it would not be good to give a leg up to existing establishments even in respect of their hiring practices while requiring new competitors (who are already trying to catch up) to meet a higher criterion.

Since the interpretations of both these sub-clauses are entirely subjective, there is nothing to compel any employer to not invoke this proviso. Though judicial interpretation will surely be provided, that will take an enormous amount of time and expense. It would have been better if at least some guidance had been provided.

Thus, an establishment that employs more than 49 contract workers could engage multiple contractors, each of whom employs less than 50 workers. Even though the establishment would itself be registered (under Section 3), since nobody would go before any officer for the grant of any license, the question of anyone bringing the matter to the attention of the “designated authority” to decide “whether any activity of an establishment is a core activity or otherwise” or whether it is entitled to the benefit of the proviso would not arise. Even if there is an adverse determination (that the activity was not a mere “manpower” / “mere human resource” supply and was a core activity and is not saved by the proviso), there would be several levels of challenge available to the establishment. The chances of a conviction would therefore be remote. Hence, the incentive to take this position is huge.

No real penal consequences

What further enables employers to set up such defences is the fact that there seems to be no real penal consequences for engaging contract labour in core activities that are not saved by the proviso. The penalties prescribed (Section 54) are mere fines, and imprisonment occurs only on a second conviction (Section 97). These are not serious enough to stop employers from taking this line. Hence, the position of the workers is no better than what it is under the CL Act where if such a contract is not registered an automatic regularisation does not happen. Even though this lacuna in the CL Act has been known since long, no effort was made to plug it, thereby also disclosing an approach to further marginalise the workers.

Contrast this with the position when a contractor goes to obtain a license under the CL Act. He is required to show his work order and, if the licensing officer believes that it is for work which is prohibited under a notification, a license would not be granted. Moreover, the license that he would be granted would contain several conditions that would oblige the principal employer to ensure certain minimum benefits to his workers. That would no longer be the case. Thus, despite the apparent prohibition of contract labour in the “core activities” of establishments it would be very difficult for contract labour to get regular employment even in what might be their “core activities”. Furthermore, now they won’t even receive the few benefits that the license conditions required the principal employer to ensure. This is what is different and will make it much harder for contract labour to be regularised or to receive fair treatment.

What constitutes “core activities” of an establishment?

It is also noted that even as there is guidance on what cannot constitute the “core activities” of an establishment, there is no guidance on which of them would. Indeed, it would be extremely difficult to do so simply because there are too many varied types of work. Hence, when this question arises, every officer would have to decide based on his own judgment. Even then, as noted above, arguments can be made that they should be permitted under the other clauses. This provides enormous scope for corruption, as also for legal challenges. The very fact that similar work in another similar establishment has been held not to constitute its “core activity” would itself be a ground to challenge an adverse order.

For instance, is the job of “trolley retrievals” a core activity of an airport? Here the strange case of the 2004 central Government notification prohibiting employment of contract labour for trolley retrievals at the airports at Delhi is noteworthy. Why was such a notification not issued for other airports as well?

All that was required under that Act was guidance on the threshold of “number of whole-time workmen”. Not only has that not been done, but the proviso introduces further confusion.

After all, all airports come under the central Government and under Section 10 of the CL Act one of the relevant considerations is “whether it is done ordinarily through regular workmen in that establishment or an establishment similar thereto”. If this could happen under the CL Act, since the Code does not even have a similar provision (but prescribes that “the normal functioning of the establishment is such that the activity is ordinarily done through contractor”), such examples are likely to multiply under the new regime, thereby giving enormous powers to the officers, also leading to enormous litigation.

This is why the approach of the CL Act that prescribed inter alia that “whether it is done ordinarily through regular workmen in that establishment or an establishment similar thereto” and “whether it is sufficient to employ considerable number of whole-time workmen” provided reasonable objective criteria for guidance. All that was required under that Act was guidance on the threshold of “number of whole-time workmen”. Not only has that not been done, but the proviso introduces further confusion.

Would this disable contract workers from raising disputes

After all this, it’s not as if the workers will have no remedy. Though for workers engaged in the expressly excluded categories under Section 2(p) the option of seeking regularisation by seeking an order of abolition of contract labour would now be excluded, the option of raising an industrial dispute contending that the “control and supervision” of their work really lay with the principal employer would remain, though it is an extremely difficult path.

However, what this also illustrates is that, since no structural change has been brought about, these provisions will not bring an end to disputes. Hence, employers will continue to need their supervisors and legal advisors, and we would not have achieved very much.

Since most employers are extremely wary of contract labour seeking regularisation in their services, they usually insist that the contractors replace / rotate them frequently. This attitude is unlikely to change until the Codes have settled interpretations, and possibly even afterwards.

This also means that the workers do not get enough time to acquire higher skills in the jobs they are performing and hence goes against the stated aim of “Skill India”. In a rapidly moving world, where we already suffer from a very poorly educated workforce, our best hope is to at least skill them in their jobs so that they could at least perform one task with great expertise. With this approach we risk being left behind forever due to our own choices.

Higher threshold for retrenchment and closure

The Codes raise the threshold for industrial undertakings to take government permissions for retrenchments and closures from 100 to 300 workers.

This will cause major labour unrest for a very small number of our establishments that fall within this size of workforce and are the better ones and they often extend more reasonable terms of service to their workers who are usually unionised and have long term settlements with their employers.

These workers would have much to lose if they were to be retrenched and are unlikely to accept either their retrenchment or contractualization without a fight. If a fight indeed occurs, it is quite possible that at least a few major establishments would be forced to enter into settlements with their unions agreeing not to retrench existing regular workers. A few of them doing so could have a domino effect and others will feel enormous pressure to also fall in line. If they don’t settle and if there are strikes in these large establishments, our good industries would be engulfed by industrial unrest.

Hence, it is quite possible that to address this concern (and to avoid short-term unemployment) the government might agree to an amendment clarifying that (even if the threshold would rise to 300 for the future) at least the retrenchment of existing workers would not be permitted by establishments that fall within this range.

However, the bigger danger is that the government could be forced to roll back the number to 100 or some other number in between. That would be a major defeat for the government. For these reasons, if the government wishes to persist with these Codes, it should at least prescribe that for existing establishments the threshold of 100 would continue to apply for a defined period (say 5 years) so that all parties can prepare for that day.

But what if the number remains at 300? That would not take us into the big league of manufacturing. The world has moved on to manufacturing at truly huge scales and if we wish to compete, we will have to remove this artificial restraint on our industries altogether. It gives too much power to bureaucrats who don’t have the competence to run a business and hence should not be directing those who do on how to do so.

Such interference is often the reason for eventual industrial sickness which does not help anyone. It breeds corruption and opens up the field for political activity at the expense of what ought to be a pure issue of economics.

Of course, even this marginal change would be welcomed by industry. Many enterprises that did not expand so that they would not fall foul of this limit would feel emboldened to do so. Those that had expanded by opening multiple establishments might consolidate them for better economies of scale. But how far would that take them? For SMEs engaged in handicrafts and other small industry 300 might be a good number. However, it is not so for heavy industry which typically employs thousands. They would continue to be governed by the same regime of permissions. Moreover, the establishments that engage more workers would be tempted to engage them as contract labour, who are likely to receive only the bare minimum that the law prescribes and are unlikely to ever acquire the skills needed for a world market. Hence, this reform will not take us into the big league of manufacturing.

In any case, even this reform is unlikely to be accepted by the unions because it seeks only to give greater freedom and power to managements, without giving the workers anything in return. Those who feel robbed of their rights and who have reason to believe that they would be worse off will fight. With this “reform” they will see only more suffering in their already difficult lives. They have little to lose. If we are to win their cooperation, then they must be enrolled into this project by giving something valuable in return.

Due to the change in threshold for employing contract labour several existing establishments that currently employ 20-49 contract labour and millions of workers who work in them would be immediately affected. One of its consequences would be that the condition currently imposed on the licences that the contract labour would receive similar wages rates and benefits as workers employed for same or similar work would cease to apply to such establishments, and they would now be able to pay them lower rates and benefits. Furthermore, several other establishments that currently employ less than 20 will feel free to employ more and those that employ just over 49 will reduce their number to employ within this range.

Chances of explosion of litigation not only by managements and unions against the government, but also between managements and unions are likely to increase. The settled interpretations of provisions and definitions would no longer hold the field.

At the same time, since under the Industrial Relations Code the threshold to require industrial undertakings to take government permissions for retrenchments and closures has been increased from 100 to 300 workers, chances are that many existing establishments will retrench workers and engage new or old workers afresh as contract labour.

But the consequences of all this would be that for some time there will likely be a lot of turmoil in the employment space. While it is possible that in the immediate term this might lead to a net increase in overall employment, it would be as contract labour and the prospects of such workers finding regular jobs will recede and it will lead to marginalising them further.

Chances of explosion of litigation not only by managements and unions against the government, but also between managements and unions are likely to increase. The settled interpretations of provisions and definitions would no longer hold the field.

Definition of wages and fixed term employment

The first major change is the proposed common definition of “wages” instead of the seven under the 29 Acts sought to be replaced. While multiple definitions were indeed problematic, over a period of over 75 years enough case law had developed around them, and managements had learned to live with them. What the new extremely complex definition means is that the pandora’s box would be reopened. The new definition is poorly drafted and will create serious problems, leading to a potentially large number litigations. It also bears the risk of forcing entities to shut down because they cannot bear the burden that the new definition imposes.

At 426 words, this new definition is one of the longest in any legislation and has two provisos. It opens with a broad sweep bringing “all remuneration” within its scope. It then expressly includes three named items and names 11 items that it “does not include”. However, there are several components of remuneration / benefits known to industrial law that are given by establishments to their workers that don’t find mention in either of them.

For instance, “any commission payable to the employee” is excluded. Then what about incentives? Would they be excluded as “commission” or included under “all remuneration whether by way of salaries, allowances or otherwise.” Since industrial laws define incentives by various names, the better course would have been to either include or to exclude them all. Next is about the status of ESOP (Employee Stock Ownership Plan). It often vests after several years of service at a price fixed several years previously. Are they to be valued according to the existing market price on the date of vesting or they will be averaged over this period and added back to the “wages” of each month? Can they be claimed under this Act? There is no clarity.

There are also items that are mentioned in a manner that leave one confused. For instance, it does not include “any bonus payable under any law for the time being in force, which does not form part of the remuneration payable under the terms of employment”. But “bonus payable under any law for the time being in force” is by law “part of the remuneration payable under the terms of employment” (as also bonus paid under a settlement or contract and “production or productivity” bonus which is also paid in accordance with the statute) and would be included under the opening phrase (“all remuneration whether by way of salaries, allowances or otherwise”).

Hence, if one is to understand the meaning of this expression, it can only refer to gratuitous payments styled as bonus. If so, this could have been better achieved by excluding “gratuitous payments by whatever name called”. In other words, payments that employees cannot demand as a matter of right, and over which they cannot file any claim before any court or authority.

Then there is the exclusion of “remuneration payable under any award or settlement between the parties or order of a court or Tribunal”. This is understandable in cases where an award or settlement prescribes a lump-sum payment. Such an award ought not to have unintended consequences towards other liabilities unless specifically directed. However, what if the award or settlement was pursuant to a demand for enhancement of emoluments? Would they have no recognition as “wages”? Even to the extent that they are prospective and form part of the contract of employment going forward? And would the consequence also be that an employee would not be able to make a claim under the Code on Wages for payments due under an award or settlement and must file a civil suit?

The first proviso to this definition requires that if certain excluded components exceed a specified percentage, the excess would be added back to “wages”. This seems to have been prescribed to curb the tendency of employers to split the emoluments of employees to meet the obligation to pay minimum wage while avoiding paying full contributions on PF and ESI and the outgo towards gratuity or retrenchment compensation. Though the intent behind this provision may be sound, the purpose would have been achieved because the same definition had been adopted across all the FLC. This proviso, therefore, complicates the matter without significant benefit for the workers.

Consider for instance that bonus is usually paid either once or twice (interim bonus) a year. Often some components of wages change during the interim. They could also fluctuate based on the number of days a person has worked. Since bonus is paid as a percentage of the total wages paid during the previous period of one year (which does not correspond to the period in which it is being paid), these fluctuations do not matter. However, if a part of it is to be added back to wages, then we need to know if it would be spread evenly over the relevant 12-month period that was considered for computing the amount or if it would be added back in the month(s) it is actually paid in. This is important because the gratuity of an employee is calculated according to his last drawn wages and the “average pay” for the purposes of computing the retrenchment compensation is calculated based on the previous three calendar months wages.

The second proviso adds a different set of components back to wages, but only for the purposes of “equal wages to all genders and for the purpose of payment of wages”. Surprisingly, one of these is “remuneration payable under any award or settlement between the parties or order of a court or Tribunal”. How can anyone know beforehand that all payments that would be awarded or negotiated would be capable of gender neutrality. For instance, if male workers are given paid paternity leave, how would that be given to women employees. Would they get it in addition to maternity benefit? If so, management may hesitate to concede such a benefit.

The second proviso also states that these four items would also be taken “for the purpose of payment of wages”. Does that mean that these items would be so counted only for female employees and not for male employees? Does it also mean that the other 5 items would be taken only for the purpose of computation of wages and not “for the purpose of payment of wages”? What would the effect of that even be?

Large retrospective liability imposed on employers

The bigger problem with this definition for employers is that it includes several components that were previously not included under the corresponding definitions for the computation of PF, ESI, gratuity, bonus, and leave encashment (made fully encashable by right under another Code which was not the case earlier). Consequently, several employers are likely to find that since the date that these Codes came into effect their liability on account of some of these has gone up significantly. Some of them (PF and ESI) would have to be paid starting immediately, while the liability for bonus and leave encashment would be faced in time.

While an employer might provision for these since they are mostly future liabilities, there could be a significant additional liability for gratuity for past periods. Though it would be payable on future dates when the employees leave service, the employer would have to make provision for it now for these enhanced future liabilities for past periods.

Several employers might find it difficult to even pass on the additional recurring liability just going forward, let alone the large liabilities for past periods. This could result in closures and retrenchments, which would be rough on the workers as well, and it may well be that in some cases they might not even receive their full terminal dues calculated according to the new definition because the employer had not provisioned for such enhanced liabilities.

The effect on long-term settlements

The new definition could also upset long-term settlements between managements and unions. If this new definition were to be applied to existing settlements over wages and other conditions of service, there could be cases where significant unintended consequences could result in the financial condition of the employer being materially impacted.

Such employers might not accept this definition as the basis for interpreting such settlements and there could be much litigation over this. Hence, the Codes ought to have clearly prescribed that such awards and existing settlement would be interpreted according to the old definitions, even if it might have also prescribed a date by when fresh settlements must be entered into. Parties would then have had some time to resolve these issues fairly.

The Code on Wages does not say what may be claimed before the prescribed authority but leaves it to be inferred. But from Section 59 which prescribes that “a claim has been filed on account of non-payment of remuneration or bonus or less payment of wages or bonus…” are we to understand that claims can also be made for all the 11 expressly excluded components of “wages”? After all, if they are “remuneration” (and are excluded only for the purposes of the definition of “wages”) then they should be so recoverable.

Since Section 57 forbids claims being filed before courts that “could have been recovered under this Code”, should an employee who has a dispute about ESOPs perforce file his claim before such authority alone? This is negligent and will lead to unnecessarily burdening our Courts with disputes that could easily have been avoided by proper drafting.

While on the subject of negligent drafting, it’s worth mentioning that several other provisions of this Code also indicate a negligent approach to their drafting. For instance, the definitions of “employee” under Section 2(k) and of “worker” under Section 2(z) use different expressions.

In reality there are two definitions

One of the selling points of these Codes was the claim that seven definitions of wages have been combined into one thereby making compliances easier. However, effectively there are two definitions for, the “minimum rate of wages” that may be fixed by the appropriate government under Section 7 of the Code on Wages may consist of “a basic rate of wages” [which seems to mean the same as “basic pay” used in Section 2(y)(i) and not “wages” used in Section 2(y)], “a cost of living allowance” [which seems to mean “dearness allowance” as used in Section 2(y)(ii)], and “the cash value of concessions in respect of supplies of essential commodities at concessional rates, where so authorised…” [but this is significantly different from “the value of any house-accommodation, or of the supply of light, water, medical attendance or other amenity or of any service excluded from the computation of wages by a general or special order of the appropriate Government” (more on this expression later) used in Section 2(y)(b) but is the same as the expression used under Section 4 of the erstwhile Minimum Wages Act].

Consider the fact that under the erstwhile Minimum Wages Act the definition of “wages” prescribed that it “means all remuneration, capable of being expressed in terms of money, which would, if the terms of the contract of employment express or implied, were fulfilled, be payable to a person employed in respect of his employment or of work done in such employment and includes house rent allowance, but does not include …”.

Hence, when Section 4 defined “basic rate of wages” people knew which components were included and which were not. Pertinently, “dearness allowance” was not mentioned. Rather, Section 4 expressly added a “special allowance” which they called “the ‘cost of living allowance’” to the minimum wage. When rates of minimum wages were revised, often merely this “‘cost of living allowance’” was enhanced and called “dearness allowance”. Under the present Section 7 the expression “‘cost of living allowance’” has been retained. Effectively, “dearness allowance” has been added under Section 7 of the Code.

But if it is now a part of wages under Section 2(y). How can it be added twice, once as “dearness allowance” and then as “‘cost of living allowance’”? This cannot be the intent. Therefore, the expression “wages” that is used in “a basic rate of wages” under Section 7 of the Code cannot mean wages as defined under Section 2(y) and must mean only basic pay as used in Section 2(y).

Consider further that the expression under Section 2(y) says that it does not include “the value of any house-accommodation, or of the supply of light, water, medical attendance or other amenity or of any service excluded from the computation of wages by a general or special order of the appropriate Government” while that under Section 7 prescribes “the cash value of concessions in respect of supplies of essential commodities at concessional rates, where so authorised…” is included. Do they mean the same? Perhaps not.

If the meaning of these expressions (or any of them) were the same, then would it not have been better to use the same expressions in Section 2(y) and Section 7? But it appears that at least “the cash value of concessions in respect of supplies of essential commodities at concessional rates, where so authorised…” is not the same as the expression used in Section 2(y)(b). If so, would it not have been better to break up Section 2(y)(b) into one part that corresponded to this expression and another that was in addition thereto?

There is another problem with the expression “the value of any house-accommodation, or of the supply of light, water, medical attendance or other amenity or of any service excluded from the computation of wages by a general or special order of the appropriate Government” used in Section 2(y). Does the expression “excluded from the computation of wages by a general or special order of the appropriate Government” apply to all the items enumerated under sub-clause (b) or only to “any service”, or to “other amenity or of any service”, or to “medical attendance or other amenity or of any service”, or even to “the supply of light, water, medical attendance or other amenity or of any service”? In other words, which of the mentioned components require a “general or special order of the appropriate Government”? This could give rise to much litigation where the rules of grammar would be pressed into service to determine its true scope and will lead to unnecessary litigation which better drafting could have avoided.

Thus, not only does this Code effectively prescribe a different definition for the purposes of determination of what would be counted for the purposes of determining whether minimum wages are being paid to a worker, but it also uses complex expressions, thereby adding to the confusion.

Fixed Term Employment

To give employers the flexibility of hiring employees for fixed durations the Industrial Relations Code introduces the concept of “fixed term employment”, while requiring that such employees be paid benefits proportionate to the periods served. However, a closer examination reveals that nothing of value has been added. Rather, it would even be very risky for managements to exercise this option when another (better) option is already available.

Corresponding to this new definition, the definition of “retrenchment” has also been amended and the “termination of service of the worker as a result of completion of tenure of fixed term employment” is now expressly excluded therefrom. Consequently, the only difference in the consequences of termination of such a person would be to free the employer from the necessity of observing the last-come-first-go principle under Section 25G (new Section 71), being obliged to offer employment to such persons under Section 25H (new Section 72) and of obtaining prior permissions under Chapter VB (new Chapter X).

Sub-clause (b) of the definition of fixed term employment guarantees the worker “all statutory benefits available to a permanent worker” without requiring him to complete “the qualifying period”. It might sound good, but what might these “statutory benefits” that require a “qualifying period of employment” be? Since “allowances and other benefits” is dealt with under sub-clause (a), gratuity is expressly dealt with under sub-clause (c), and PF no longer requires any qualifying period of employment, the only other “statutory benefit” that requires such a “qualifying period” is the notice period / wages and retrenchment compensation that have been carried forward (from Section 25F of the Industrial Disputes Act) under Section 70 of the Industrial Relations Code.

Since the compensation would be paid “proportionately according to the period of service rendered”, it would require in each case to determine this period. Under the Industrial Disputes Act and the Payment of Gratuity Act the “one year” and “six months” can be merely 240 / 120 working days respectively. Under this Code, would a worker who has put in 8 months (about 240 days) be taken as having completed one year or would he have completed 8 months?

Under the Industrial Disputes Act and the Payment of Gratuity Act the courts have also held that Sundays and other paid holidays falling in between must also be counted as working days. Hence, there would now be fresh litigation over the computation of “the period of service rendered” under this clause. Furthermore, would there be a notice period requirement for those who have completed one year of service even though it was a “fixed term employment”?

Now, let us look at the old sub-clause (bb) which has been continued under the new sub-clause (iii) and would thus also remain available to employers, and see how they would differ in application.

The old sub-clause (bb) permits the employer to terminate the workers:

i. By non-renewal of the contract of employment on its expiry; or

ii. under a stipulation in that behalf contained therein.

The proposed sub-clause (iv), however, only permits termination upon “completion of tenure of fixed term employment”. Since it does not also permit termination “under a stipulation in that behalf contained therein”, it might not be permissible to terminate a “fixed term employment” contract earlier than on the completion of its “tenure”.

Consequently, the only option for an employer might well be to pay such an employee his balance dues for the remaining period of his “fixed tenure” along with “all statutory benefits… proportionately according to the period of service rendered”. Now, would “the period of service rendered” of such an employee be the period actually served or the period for which he has been paid?

A few other amendments (or the lack thereof) in relevant provisions is worth analysing. The First Schedule to the Industrial Disputes Act prescribes “Matters to be provided in Standing Orders…”. The first entry in the corresponding Schedule of the Industrial Relations Code has been amended to include “fixed term employment” and reads as under:

Classification of workers, whether permanent, temporary, apprentices, probationers, badlis or fixed term employment. Under the Fifth Schedule to the Industrial Disputes Act, “Unfair Labour Practices” inter alia contains an entry as under:

“(10) To employ workers as badli workers, casuals or temporaries and to continue them as such for years, with the object of depriving them of the status and privileges of permanent workers.”

Interestingly, this entry in the new Second Schedule to the Industrial Relations Code has not been amended to include “fixed term employment”. Hence, the question arises whether employing workers under “fixed term employment” contracts and continuing them for years could be an unfair labour practice at all. It could be argued that since it would not simultaneously meet the requirements of continuity of service and the “privileges of permanent workers” it would not be an unfair labour practice. It could conversely be argued that the proposed sub-clause (iv) being silent on renewals [unlike sub-clause (iii)], such a contract cannot be renewed and the absence of any entry regarding workers under “fixed term employment” contracts in the new Second Schedule is an indication that (unlike badli workers, casuals or temporaries) such contracts were never intended to be extended.

Thus, the proposed “fixed term employment” contracts will be mostly useless to employers. Yet, there will be some who will take this route without understanding these nuances only to later regret them.

Finally, there is nothing in the proposed legislation to indicate what proportion of his workforce an employer may hire on fixed term employment contracts. There was no such indication under Section 2(oo) (bb) either and that led to a lot of litigation. However, now we know that it has been given a very limited play by the courts. Given this, it is unlikely that “fixed term employment” contracts will be given any greater play.

Given all this confusion, why would employers use this exception and expose themselves to prolonged litigation over a new provision when the exception under the old Section 2(oo)(bb) also remains available and it does not even oblige them to extend the same “hours of work, wages, allowances and other benefits”, or to proportionately pay other statutory benefits, while permitting them to terminate after repeated renewals or earlier than its scheduled expiry under a stipulation? Thus, the proposed “fixed term employment” contracts will be mostly useless to employers. Yet, there will be some who will take this route without understanding these nuances only to later regret it and there might be some unions who will get unnecessarily riled up merely because such an option has been introduced. It will also impose a burden on the judiciary that it is ill equipped to handle.

Gig workers and procedural issues

The approach taken towards “gig work” and “gig worker” as also “platform work” and “platform worker” by the Code on Social Security is likely to fail in what it seeks to achieve. We broadly understand that “gig work” means short-term or non-permanent work, and that “gig workers” don’t have any regular “employer” but are employed from task to task. (These expressions are often used interchangeably with “platform work” and “platform worker”.)

It is necessary to extract the definitions of “gig worker”, “aggregator”, “platform work” and “platform worker” under the Code on Social Security which are as under:

“gig worker” means a person who performs work or participates in a work arrangement and earns from such activities outside of traditional employer-employee relationship“.

“aggregator” means a digital intermediary or a marketplace for a buyer or user of a service to connect with the seller or the service provider.

“platform work” means a work arrangement outside of a traditional employer-employee relationship in which organisations or individuals use an online platform to access other organisations or individuals to solve specific problems or to provide specific services or any such other activities which may be notified by the Central Government, in exchange for payment.

“platform worker” means a person engaged in or undertaking platform work.

These definitions find place only in this Code and there is no reference to any such person in any of the three other FLCs. Hence, the definition of wages as occurring under the Code on Wages will not apply to such workers, thus leaving them to seek their remedies before the civil courts.

The major sectors that currently employ gig workers are ride-hailing services (Ola, Uber, Rapido), food delivery services (Zomato, Swiggy), on-demand home and professional services (Urban Company), and end-to-end logistics and delivery platforms (Porter, Delhivery). In 2021 they were estimated to employ over seven million workers. In time several other sectors will also emerge or change over to gig work as the preferred method for delivery of products and services. A 2022 NITI Aayog report estimated that by 2029 nearly 23.5 million workers will be engaged in the gig economy. This tells us how important this sector is and will be to our economy and why it is necessary to regulate it for the good of the entire economy.

The need for regulation

India now has about 40 million 4-wheelers and about 200 million 2 and 3-wheelers, leading to enormous traffic congestion, road rage, loss of time commuting, air and noise pollution, burning of oil and foreign exchange and contributing to global warming.

Then there is the considerable capital expenditure that the middle classes and the poor have to lay aside for personal vehicles. At the same time digital platforms are being extensively used for delivery of products, food, and services at the home of the consumer, providing them convenience and cost savings, thereby also reducing the need for retail space, bringing down the value of real estate (and making it more affordable) while providing millions of jobs. However, most of the delivery agents are hired as gig workers for each delivery. Since the industry is unregulated, these people are largely being exploited. They are made to compete for each delivery thereby leading to them working long hours and driving irresponsibly on the roads which puts them as also others at risk.

If the benefits of available technologies were properly leveraged, we could ensure decent conditions of service for the people who work in these jobs, reduce the traffic (with all the attendant benefits), and enable the employment of even greater numbers of people in very cost-effective ways, thereby being a huge boon to the economy especially for a country like India which can benefit enormously from the more efficient utilisation of our resources. But to achieve that we must address the problems faced by these workers so that they willingly participate in this endeavour.

According to several studies the people engaged in these jobs are often not even able to make a minimum wage. Since they are not recognised as “employees” by the platforms that hire them they are not extended social security benefits. Rather, they are engaged through “aggregators” and super “aggregators” who enter into contracts with the platforms, essentially to supply labour. The “aggregators” treat them as under “contract” and not as employees or even as “contract labour”, hence don’t comply with labour laws. These gig workers might be receiving the full compensation due to them under their contracts because they are usually paid electronically, and to that extent they might be better off than the workers working as “contract labour” in other jobs. However, that matters little to someone who unable to make even a minimum wage, who often has a migrant status and no legal redress. This is contract labour under a shining new name.

Can a gig worker never be an employee?

Even though we all understand that gig workers don’t have any regular employer but are employed from task to task, the law does not always follow the common understanding of words and phrases, especially in the matter of employment relationships, and it is by no means certain that under the Industrial Disputes Act (or even the Industrial Relations Code) these persons would not be held to be the employees of these platforms. Uber has already been held to be the employer of their drivers in UK and New Zealand. Since these are common law countries, these and other similar workers in India could well hope to receive similar recognition in India as well.

However, since of the FLC only the Code on Social Security recognises gig or platform workers, it makes them fear that they would be excluded from workers under the other three Codes. Hence, they lose the status they currently hope they could enjoy by virtue of likely interpretations placed by the courts to the previous statutes. They are suspicious that the attempt is to make them independent contractors or contract labour and is one of the reasons that the unions oppose the FLC in their present form.

The current approach would solve nothing, and the courts might yet hold such workers to be the employees of some of these platforms. Since neither of the other three Codes expressly excludes such workers from the definition of worker, through the application of the control and supervision test they could well be held to be the employees of these platforms. Moreover, if they come to the finding that the attempt by these Codes is to reduce their status, the Codes could be struck down. Hence, this Code does not even achieve clarity, even as it has managed to get the workers angry at what it proposes.

The Code defines a gig worker as someone who “earns from … activities outside of traditional employer-employee relationship”. However, what is a traditional employer-employee relationship? The Code contains no definition of this expression. Hence, it will require judicial interpretation and, that will necessarily lead to long and expensive litigation, where the workers are usually at a disadvantage. This is itself a good reason not to adopt this path. If the Code intended to make doing business in India easier, it ought to have provided clarity on this issue, not open up a new field that has enormous employment potential to litigation only because of poor legislative drafting.

It is true that before Uber we could not hail a taxi through a digital platform, but was the taxi driver not an employee of the owner of the taxi stand or travel agencies? Merely because a digital platform has now enabled the user to connect with the driver without speaking with the intermediary, that ought not to change anything between the taxi driver and the owner of the taxi service (Uber / Ola).

Likewise, is a food delivery service outside of traditional employer-employee relationship as between the delivery person and the owner of the service? While previously not every small eatery had dedicated delivery boys and often the same few persons delivered for several establishments on per job basis, the larger establishments did indeed have dedicated people.

What the digital platforms have enabled is the aggregation of restaurants (and other establishments) to bring about greater efficiency of service. This phenomenon of aggregation has also changed the owner of the service from the restaurant to the platform. However, since in effect the service remains the same (food / product delivery) the employer-employee relationship between the delivery person and the owner of the service ought not to change.

It was only the owner of the small eatery who did not employ full time workers for delivery, the larger ones did. When comparing those working for Zomato and Swiggy one much consider the past relationship of larger establishments with their delivery persons. In other words, it should remain a traditional employer-employee relationship. Consequently, such a person would not be a gig worker.

As a matter of fact, when we examine the relationship by applying the test of control and supervision, we see that now the platform owner has far greater control over them and can (if it wishes to, and they often do) supervise them better since they can track the movement of the delivery person throughout the journey (often even the customer can do that). The customer can also write a review and that can have adverse consequences, also give a tip (as they “traditionally” did).

Hence, it is quite possible that under the Industrial Disputes Act and Contract Labour Act several of these platforms would have been held to be the employers or the principal employers of these workers, and this might be so also under the Industrial Relations Code. In that event, these workers would be entitled not only to minimum wages but also to social security benefits.

For these reasons, the use of the expression “outside of traditional employer-employee relationship” in these definitions is problematic. Apart from creating apprehension in the minds of these workers they could lead to much litigation not only on whether a given service fell within their scope, but also on the validity of these Codes. Hence, if it nevertheless wishes to go down this path then the government would be advised to be rigorous in defining these expressions and it is not a good idea to leave these riddles for the courts to resolve. In the absence of clarity, it would have been better to leave the law as it is and to let the courts decide the nature of these relationships based on already accepted principles. Poorly drafted new legislation could create enormous confusion.

The Seventh Schedule (on classification of aggregators) mentions ride sharing services. However, if what was meant were services like Uber and Ola, it ought to have said “ride hailing services” (or both). These nomenclatures are important because their interpretation depends on the words and phrases used. Of course, the context is important too, and the courts might yet understand and interpret this provision to also point to Uber and Ola. However, there are some bus services and other ride sharing services (where one can book / reserve a seat on a vehicle) and hence, it is possible that such an expression might create difficulties even for the courts. Hence, such drafting gives one the impression that those who were given the task of drafting these provisions have been negligent.

Social security benefits prescribed

The Code is called The Code on Social Security. Hence, all the schemes mentioned therein are deemed to be social security schemes. Those that are expressly mentioned are PF, ESI, gratuity, maternity benefit, employee’s compensation (for death, injury or disease). This is what a plain reading reveals, though one might argue that bonus is also a form of social security.

Chapter IX (Sections 109 to 114) applies to “unorganised workers, gig workers and platform workers”. Section 114 prescribes what social security schemes might be notified for gig and platform workers. It is noted that neither PF nor gratuity is even contemplated, and though these schemes could include life and disability cover; accident insurance; health and maternity benefits; and old age protection, they are unlikely to be the same as under ESI (else it would have been simpler to say so). Moreover, the contribution to be paid by the aggregators for the funding of these schemes “shall be at such rate not exceeding two per cent., but not less than one per cent. … of the annual turnover of every such aggregator” and “the contribution by an aggregator shall not exceed five per cent. of the amount paid or payable by an aggregator to gig workers and platform workers”.

Such a contribution cannot fund very much, and though these provisions say that these schemes might also be funded by the government, it is doubtful that the government would fund it enough to provide any of the mentioned benefits in any substantial way. The rate of contribution also indicates that ESI would not be extended to them, but a much smaller protection. Hence, gig and platform workers are not to be extended any substantial benefits, even though many of them face a lot of danger on the roads every day.

Since they are also not treated as employees, they would presumably also not receive bonus (though the delivery platforms often prescribe incentives for their delivery agents on meeting certain targets, but these are contractual and not statutory). Clearly therefore, these workers will not receive any substantial social security benefits and even those that are indicated under the Code are only promised in the future.

No forum for gig and platform workers

Since gig and platform workers are excluded from the definition of “worker” under the Industrial Relations Code and the Code on Wages, none of the mechanisms provided thereunder would be available to them for the redressal of their grievances.

If they are given some social security benefits, they might be given some other fora to raise concerns regarding them. However, if there are unpaid amounts owed to platform owners, they would be unable to approach the authorities under either of these Codes and hence must necessarily go before civil courts.

They would also find it extremely difficult to raise industrial disputes about their conditions of service because managements will argue that they are not even workers as defined under the Industrial Relations Code. Though the law is that whether a person ought to have the status of a worker must be decided by the Labour Courts and disputes cannot be dismissed at the threshold, since the new Codes virtually expressly exclude them from such status that might no longer apply in their case. This too would require considerable litigation to resolve.

Consumer interest

Since the approach of the Code is to treat these workers as on contract, mass agitation or litigation is likely to ensue. In the long interim there would be uncertainty about their status which can also be very problematic for consumers. Would a commuter be able to sue Uber for an accident caused by driver error or drunken driving? Should not a user be able to sue Uber for accident caused due to it permitting a driver to drive in excess of 8 hours a day or without a break, given that Uber has the technology to be able to closely monitor his working hours? What if the insurance policy on the vehicle or the driving license of the driver is found to have expired or is fake or does not cover the entire liability (their drivers own their vehicles and are required to obtain their own insurance policies)?

After all, employers are held vicariously liable for the actions of their employees. Or will the law deal with this employer-employee relationship differently merely because it is not a traditional one? In a recent decision the Supreme Court has held that employers are not responsible for checking the validity of the license of the driver. Should not the law clearly make it the responsibility of the entity that makes such services available to ensure that they are in place? In any case, why should this conundrum be left for the courts to resolve? These questions should be addressed so that they don’t remain in flux for years, even as litigation explodes even between users and these platforms.

Potential adverse consequences for employers

The refusal of employers to treat them as employees could also be very costly for them in the long term because if they are later held to be their workers (or even contract labour), their PF and ESI contributions with interest and penalties as also back wages could be very substantial. Many of them could collapse under the weight of these liabilities, thereby leading to enormous unemployment, unrest and litigation, and could also dissuade others from setting up enterprises in India.

These platforms are competing in very hotly contested space and are often losing money on their operations that are being funded by venture capitalists in the hope that they would be the last one left standing once the others have been forced to shut down. Hence, they cut corners and one of them is the payments that they make to these workers who are the most vulnerable in the chain. The workers of the platforms that shut down will therefore never recover the dues that are owed them even if they succeed in their court battels with them. Is that a desirable situation?

Minimum wages and benefits cannot be left to market forces

The law has since long been that minimum wages and benefits cannot depend on market forces. Unfortunately, today the nature of the new economy is that any platform that treats workers as employees (or even as contract labour) and gives them minimum wage and social security benefits, would price itself out of the market. The solution is not to formalise this arrangement but to require them all to provide certain minimum benefits so that neither has a price advantage over others. That would necessarily mean a higher burden on the consumer.

But if the consumers are benefitting from these services, they must bear whatever burden is essential to ensuring an orderly development of these platforms for the benefit of the society as a whole, as also their own interest. The burden cannot be made to fall on the most vulnerable section of our society. We cannot have our conveniences at the cost of the poorest in the chain.

Procedural aspects

Some good changes have indeed been brought about by clubbing several compliances and enabling them online, and certain offences have been made compoundable. However, the number of authorities before which proceedings would lie for the recovery of dues by workers remains almost the same, with the only change being that now a claim for bonus (which was before the authority under the Payment of Bonus Act) would also lie before the authority under the Code on Wages. Hence, claims for wages can also be clubbed with claims for bonus.

However, separate authorities for PF, ESI, gratuity, maternity benefit and employee compensation continues as before. There might also be new authorities for gig workers, who have been promised schemes for life and disability cover; accident insurance; health and maternity benefits; and old age protection, as also another one for unorganised workers. Hence, nothing has been simplified for the worker, and she must still run from pillar to post to secure her dues. The employer too will continue to have to make multiple compliances and answer to multiple authorities. Only the process has been made easier.

Tribunals

However, another change is that Industrial Tribunals have been made 2-member bodies instead of the single member bodies they used to be, by prescribing that there would be one “administrative” member in addition to the Judicial member. This is not a minor matter.

Apart from creating a useless post-retirement post for a civil servant it achieves nothing. Rather, it could fall foul of Supreme Court rulings in R. K. Jain vs. Union of India – 1993 (4) SCC 119 and Union of India vs R. Gandhi (2010). In the context of the tribunals set up under Articles 323A and 323B of the Constitution, in R. K. Jain vs. Union of India, the Supreme Court had observed that it is desirable to have subject experts in tribunals who also have “legal expertise, judicial experience and modicum of legal training”.

Later in Union of India vs R. Gandhi (2010) addressing the issue of the eligibility criteria for appointment to tribunals it held that tribunals performing judicial functions must be composed of members with judicial experience or expertise, similar to that of a High Court judge.

Though the court granted approval to the appointment of officers who held the ranks of Secretaries or Additional Secretaries for appointment as Technical members of the National Company Law Tribunal, it imposed several conditions on what qualifications such persons must hold. However, the criteria prescribed for the National Company Law Tribunal cannot be applied in the case of Industrial Tribunals. Appointments to these positions could also be litigated. Apart from securing post-retirement positions for civil servants who are beholden to the government it is not seen how this would achieve anything.

Experience also shows that most two-member benches agree on most decisions. If such members were truly independent, the fact that judgments of such benches are often set aside by higher fora should mean that such benches should also disagree far more often. Since that is not the case, it appears that the second member does not really add very much value to the decision-making process. Why then have two-member bodies at the first level, that too by adding a member who has no subject knowledge? If at all, a second member should be at the appellate stage, and such person should at least be a subject expert.

One may also consider what would happen if there were a disagreement between the two members. The procedure is to place such matters before three members, and even though the previous two members are also members of such bench, the matter is argued afresh in front of all of them. How can this third person not be a Judicial member? Hence, in the event of a deadlock between the decisions of the Judicial member and the Administrative member, we must go back to another Judicial member. Would this not be a waste of time and money?

Furthermore, as per the existing provisions these Tribunals won’t have to always sit in twos, and even the Administrative members would be able to sit singly to decide several types of cases! This is insane for this provision is likely to be struck down for the same reason that the Supreme Court held that Administrative Tribunals cannot have majority Administrative members. Hence, much time will have been lost by the time they become functional.

Conclusion

It is a tragedy that when after over 70 years of independence we finally got around to addressing the issues arising out of our extremely complex and retrograde labour laws, we came up with a remedy that can only be called worse than the disease.

First, the stated objective was very modest. Leaving aside the fact that it was inevitable that such a consolidation would lead to complex issues of interpretation of existing conditions of service and hence required a very careful approach which has not been done, the larger point is that when the laws were clearly majorly flawed, a mere consolidation should not have been the goal.

Even if it had been achieved with clarity, it could not have led to very much. Moreover, it sends a message that beyond this we can’t even think of anything different. However, as noted, even this so-called consolidation has not been well executed, and a number of provisions indicate a negligent approach.

What is really disappointing is that we have not even attempted any radical new approach that would resolve the main issues that both management and labour face which, if resolved, would lead to industrialisation at truly global scales. Rather, we have signalled that we can only do a little tinkering here and there. Is it that we don’t have any ideas or that we are afraid to try anything new? In either case we have accepted that we will at best make marginal improvements. This is not what we need.

For instance, why does the government continue to retain the power to permit or deny any industry that employs 300 or more workers permission to retrench or close down (under Chapter X of the Industrial Relations Code)? This is the flawed thinking of the 1970s that has brought us to this sorry pass. A government servant who has never run an enterprise does not know better than the entrepreneur who has invested his sweat, blood and money. The culture that allows such thinking cannot be changed by changing the number at which it is triggered but by altogether uprooting the idea from our minds. And why is the almost total contractualization of our workforce the only remedy we can think of? Labour laws came to be enacted because of the exploitation of the working class by their employers. Do we need another round of labour unrest to make us understand once again that that is not the path to industrial peace, which alone can bring growth? Why are we repeating history?

The views expressed in the article are of the author’s alone and not necessarily of gfiles.