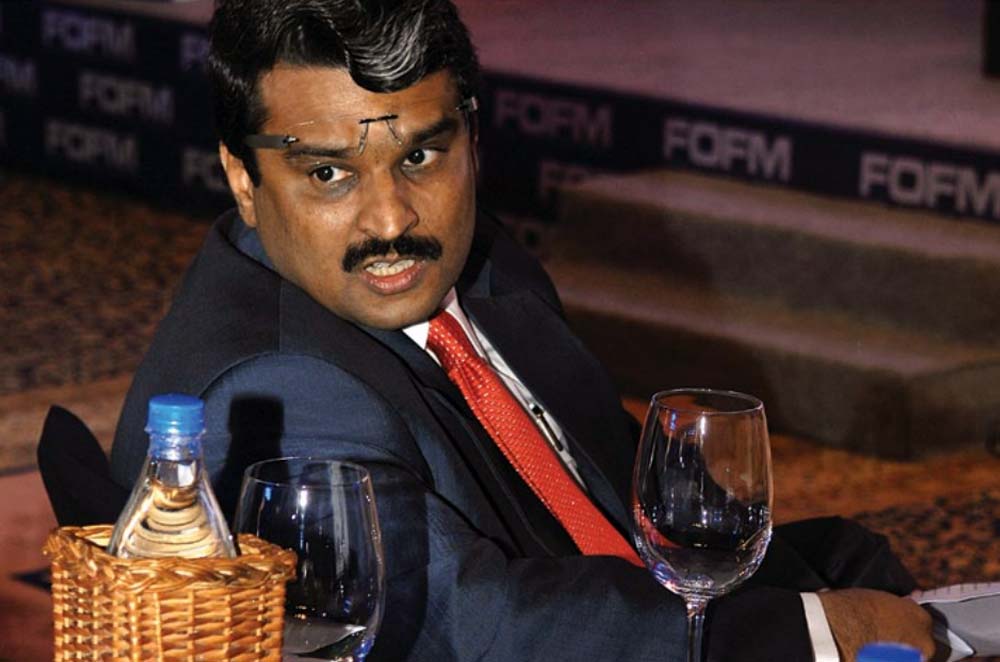

THERE was a time when Jignesh Shah was acclaimed as a pioneer in developing the commodities and futures industry in the Indian subcontinent. He was the Founder Chairman and Group CEO of the Financial Technologies Group, Chairman of Bahrain Financial Exchange Limited (average daily turnover $175 million), Vice-Chairman of Multi Commodity Exchange of India Limited (MCX), Vice-Chairman GBOT, Mauritius (average daily turnover $25million), Vice-Chairman IBS Forex Limited, Vice-Chairman Dubai Gold and Commodities Exchange (average daily turnover $2.2 billion), Non-Executive Director Indian Energy Exchange Limited, Vice-Chairman Singapore Mercantile Exchange Pte Ltd (average daily turnover $81 million), Vice-Chairman National Spot Exchange Ltd, Vice-Chairman and Group CEO MCX Stock Exchange Ltd and Director, National Bulk Handling Corporation Ltd, besides being on the board of several companies, including Bourse Africa Limited, a pan-African stock exchange yet to start trading.

Today, he is nowhere. Shah and his two lieutenants—Joseph Massey and Shreekant Javalgekar—have been declared unfit and improper, meaning they cannot be on the board, management or hold more than 2 per cent stake in any recognised commodity exchange, individually or through other entities.

The 44-year-old poster boy of India’s financial markets is today but a financial wreck. He is on the verge of losing control over all that he built—the world’s largest networks of 10 exchanges, including Indian Energy Exchange Ltd (IEX), India’s first power exchange. The number of promoter nominees on the MCX board is down to one and institutional shareholders have all but taken over the MCX-SX board. The post-NSEL crisis has forced him out of the board of MCX-SX, an exchange he set up after hectic lobbying in the government and a big fight with regulators and rivals. The jinxed NSEL exchange—a 100 per cent FT venture—is expected to down its shutters anytime now, leaving the poor investors, who pumped in their lifetime savings, in a lurch. But does anyone in the government care? All they reportedly want is that Shah should be let off without much damage.

According to the latest information available with gfiles, Shah is investing his money—Rs 200 crore out of the Rs. 12,515 crore, FT (Rs. 4,815 crore) and MCX (Rs. 7,700 crore)—in some diamond mines and real estate projects. Technically, he can afford to take another risk because it’s not his money that he is playing with.

But the moot question is, where does this place the 13,000-odd investors who trusted him with their entire savings? Why isn’t anyone trying to prevent the flight of money?

TRUST DEFICIT

There is a saying–a man is known by the company he keeps. When it comes to that, Shah has a rather dubious circle of friends. Not many people know that National Spot Exchange (NSEL) was not the only fiasco associated with Shah. His name is today linked to a string of failed commodity exchange ventures that collapsed overnight, landing thousands of investors in a financial lurch. His flagship company, La-fin Financial Services, itself means ‘the end’.

In terms of failed business ventures, the only person who comes close to challenging him is his one-time lieutenant Anjani Sinha, who presided over the shutdown of the Magadh, Ahmedabad and Safal exchanges before being picked up by Shah to head NSEL. There were allegations of fraudulent trading activities during Sinha’s tenure at all the bourses, resulting in the suspension of the board of one of them by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI).

Sinha, a chartered accountant and law graduate, was the Chief General Manager and Chief Executive of Magadh Stock Exchange (MSE) for nine years before it closed down due to allegations of irregularities in dealings of shares. A few brokers initiated legal proceedings against him and the exchange in Calcutta High Court. SEBI superseded the board of the exchange following complaints of malpractice, financial mismanagement and administrative breakdown. But not much came out and the victims were not even compensated. Many exchange brokers were found to be indulging in irregularities in issuing contract notes, non-maintenance of books of accounts, not reporting off-market transactions, not maintaining separate client accounts, delaying payment to clients, non-payment of turnover fees and non-fulfillment of capital adequacy requirement. SEBI investigators also found evidence about the prevalence of the age-old practice of buying at one exchange and selling at another, to cash in on the price differential between the two exchanges by the foreign institutional investors (FIIs).

LIKEWISE, the name of DLF Commercial Developers, the Delhi-based group, was found to be involved in the infamous Bhoruka Financial Services scam and many unlawful transactions on the Magadh Stock Exchange (MSE). The Bhoruka case came into limelight when its stock last traded on the Bangalore Stock Exchange for Rs. 5, about 17 years ago. It was admitted in the MSE at Rs. 4,490 per share by Bhoruka’s promoters and acquired by DLF.

The MSE at Patna was among the 21 regional stock exchanges in India registered as limited company, under Section 25 of the Companies Act, 1956. It was the only regional stock exchange in India to trade on the National Stock Exchange (NSE), Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE), Calcutta Stock Exchange (CSE) and Interconnected Stock Exchange (ISE). It had got clearance of CSE to do vyaj-badla and get finance in lieu of securities. MSE had also signed a MoU with the CSE to provide CSE’s online trading facility to its brokers in Patna. The SEBI refused to renew the recognition of MSE when it found that the exchange has failed to establish a settlement guarantee fund (SGF). Besides the failure to create an investor protection fund, some of the other grounds for the refusal included failure to appoint an executive director at the exchange, inadequate infrastructure, non-recovery of dues from members and listed companies.

According to the latest information available with gfiles, Shah is investing his money—Rs. 200 crore out of the Rs. 12,515 crore, FT (Rs. 4,815 crore) and MCX (Rs. 7,700 crore)—in some diamond mines and real estate projects

A few years later, Sinha was again in the news for being involved in a share-induced payment crisis as the Chief Executive of the Ahmedabad Stock Exchange (ASE), the second oldest exchange in Western India recognised by the Securities Contract (Regulations) Act, 1956. ASE, the third-largest exchange in Gujarat, did not meet SEBI’s preconditions, like $16.12 million net worth, $161 million trading turnover and 5 per cent cap on shareholding. Separate investigations by SEBI found its members to be involved in irregularities in issue of contract notes; dealing with unregistered sub-brokers; not maintaining proper client database and order books; evading carry forward margins; indulging in off-market transactions and cross-deals; delaying delivery of securities to the beneficiaries account (in one case, the written authority by one client to keep the shares in pool account was found to be unsigned); non-segregation of clients’ account; and, depositing clients’ funds into the general account (in many instances, brokers were deducting their own office and petrol expenses from client accounts).

SEBI investigations also revealed the following irregularities: No pre-printed serial numbers on contract notes and no client acknowledgement; improper maintenance of client registration and agreement forms; payment of office expenses from client’s account; delay in security pay-out from the pool account on many occasions; dealings with unregistered sub-brokers; and, non-payment of turnover fees to SEBI. Many brokers at ASE were opposed to the move to start trading in commodities because they were asked to pay Rs. 71,000, including Rs. 11,000 membership fee for the commodities exchange, Rs. 50,000 security deposit and Rs. 10,000 for trade guarantee fund. The brokers were angry because the exchange had reportedly levied these charges without any discussions with them. Finally, in March 2003, SEBI stepped in and superseded the ASE Board, led by Sinha, for failing to curb illegal vyaj-badla and carry-forward transactions by the brokers inside the exchange premises.

In a significant development, SEBI derecognised the ASE, despite it being one of the eight stock exchanges in the country that enjoyed permanent recognition like Bombay Stock Exchange, Bangalore Stock Exchange, Calcutta Stock Exchange, Delhi Stock Exchange Association, Hyderabad Stock Exchange, Madhya Pradesh Stock Exchange and Madras Stock Exchange. When Pune Stock Exchange, Coimbatore Stock Exchange, Cochin Stock Exchange, Interconnected Stock Exchange and Magadh Stock Exchange faced similar action, Sinha should have seen the writing on the wall–but he didn’t.

This even led Prakash Mani Tripathi, the chairman of the Joint Parliamentary Committee on Stock Market Scam, to comment in its report in the thirteenth Lok Sabha: “Looking at the future, illegal financing in various forms appear to be resurfacing in stock exchanges like Ahmedabad. Synchronised deals and gathering of brokers, at a fixed time on a particular day in a week, in trading hall of the exchange/corridors of the exchange to fix badla charges is common knowledge. There is need for SEBI to take immediate action.” This, seemingly, was reason enough for some regulatory agency to put a stop to people with dubious track records from taking over one exchange management after another, but this glaring necessity was overlooked.

Meanwhile, one of Sinha’s contemporary and would-be colleague, Joseph Massey, the Executive Director of Vadodara Stock Exchange Limited, left it on the verge of closure like the ASE and Saurashtra Kutch Stock Exchange.

It is intriguing how both these ‘exchange destroyers’ were allowed to join Shah without any clearance from the FMC, SEBI or RBI, that too within a few months of the ASE fiasco. Sinha was picked up by Shah as the CEO of MCX and later shifted as MD and CEO of NSEL and Director of MCX, while Massey was offered the post of MD, MCX-SX. Massey, incidentally, was one of the highest-paid employees, drawing $0.29 million from the FTIL and MCX group till he was axed.

CURIOUSLY, the first venture that Shah, Massey and Shah put together was the Safal National Exchange of India (SNX)—a joint venture between FTIL-MCX and National Dairy Development Board. Launched amidst much fanfare, it was India’s first electronic spot exchange and online platform for trading fruit and vegetables. With the vision of ‘One India One Market’ possible because of internet reach and software-enabled trading, it offered contracts in mango, onion, potato, tomato, grape and bananas in December 2007.

On the face of it, the exchange offered an opportunity to small farmers to access national markets and negotiate better price for their produce in a transparent manner, with the involvement of as few intermediaries as possible. SNX’s greatest attraction was it being an electronic spot market, offering quality, transparency and payment and delivery guarantee for the benefit of large number of sellers and buyers across the country. The seven board members of SNX included Shah, Massey, Amrita Patel, Deepak Tikku, V Hariharan, Nisar Ahmed Shaikh and Ramachandran Nathan Kutty. Incorporated on June 14, 2006, SNX initially attracted a lot of interest from farmers, but soon came to a grinding halt. One of the reasons was that the exchange management, traders and farmers couldn’t see eye-to-eye on quality, price and other business modalities. As a result, SNX was officially shut down.

Among the theories propounded for its failure was that FT and MCX, which together held 51 per cent stake in SNX, wanted to drive traffic to its 100-per cent venture NSEL, then in a nascent stage. Some investors and members also filed complaints with the Economic Offences Wing, alleging misuse of $0.80 million by SNX promoters. It was alleged that MCX-FT did not return the membership fee of $4,183 each to its 200 investors when it stopped trading without any intimation to the members. Overnight, information about its members, directors and contact details was removed from its website and SMS enquiry facility was stopped. All business development officers and supply chain employees were sacked. Interestingly, the FT’s 2010 annual report only tried to justify writing off an investment of $0.73 million in the venture without going into the reasons why it was terminated. Later, when SNX members were given the option to migrate to NSEL, it reinforced the conspiracy theory of a FT ploy to secure more NSEL members.

What followed was a trail of failures. FTIL had to sell its 100 per cent stake in Singapore Mercantile Exchange—launched three years ago for trading in metals, energy, currency and agriculture commodities—to ICE Singapore Holdings, an entity owned by Atlanta-based ICE group, for US$150 million. Today, FTIL Group’s ecosystem is in a state of flux.