MUCH of what is happening in India today should have been apparent to any discerning analyst long ago. India was on its way to becoming a major power prior to the globalization fever. It is one of the few developing countries that have enjoyed sustained growth in per capita incomes since 1950. Much of the impetus for economic growth has come from domestic sources. It is important not to exaggerate the importance of global integration.

But the country’s destiny cannot be realized so long as it is home to half the world’s destitute and illiterate, and when a third of its population lives below the poverty line. Can India’s democratic institutions that have served some of the people so well be reformed to empower the poor? Economic growth and redistributive justice is not a zero sum game in which India must choose either to pursue a rapid and urban-based double-digit growth or alternatively pursue a more equitable growth but be reconciled to accepting a slower economic growth. The success of India is owed to the miracle of its democracy and its democratic institutions and processes that has empowered the great majority of its citizens to realize their capabilities and entitlements. The failures too, ironically, stem from what may be described as democratic deficit. India has had uninterrupted democratic governance longer than Germany, Italy or Japan. India has retained a liberal Constitution and federal political institutions.

Indian democracy provided the political stability that has enabled the state to build institutions and to put in place long-term policies that have enabled India to utilize the opportunities offered by globalization.

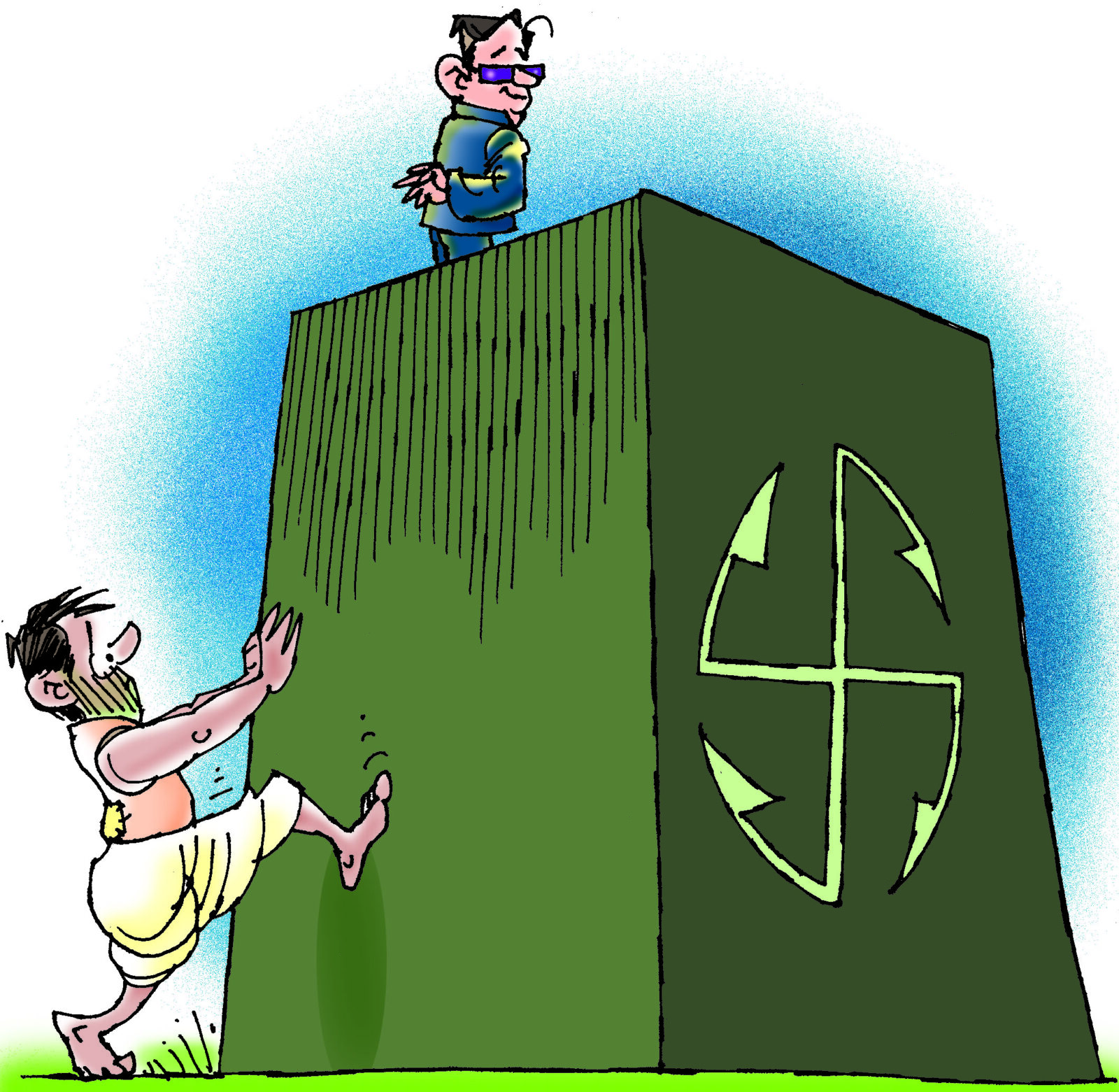

However, the same democratic institutions have failed the most vulnerable and the historically marginalized groups and communities. Between elections, the poor have no mechanisms to hold their elected leaders accountable. The influence of campaign finance, special interest groups and the dominance of big business further constrain the freedom of action of the elected representatives.

For the benefits of economic development to be equitably distributed requires recognition of the entitlement; and we know that entitlements cannot be realized without developing adequate capabilities of the poor. Only now – slowly, belatedly and reluctantly – the development community has begun to focus on the importance of the role of the government in the empowerment of the poor.

The poor remain poor not for want of resources but because they are not able to enforce their

‘entitlements’

The founding fathers of India’s Constitution had built into it provisions to create an even playing field. India was the first country in the world, even ahead of the US, to build affirmative action into the Constitution.

The inability of government to tackle poverty is not due to any inherent defect of democracy but rather to the weaknesses of political institutions and processes which have largely excluded the poor and vulnerable groups. Government works within a broadlybased consensus which is negotiated through complex bargaining amongst numerous stakeholders and powerful interest groups who have strong vested interests in preserving the status quo. There is therefore a limit to the ability of the government to persuade the groups that stand to benefit from the status quo to voluntarily give up their privileged position in the name of fair play or social justice. On the other hand the poor are largely unorganized and cannot be mobilized easily despite their large numbers. In the abridged version, democracy is reduced to the right of electoral participation periodically; and for the rest of the time the poor have come to be seen as bystanders in the game of politics. The government, faced with the conflicting demands of the articulate sections and the voiceless poor, has often sought safety by siding with the powerful.

The poor remain poor not because the solutions are not there or for want of resources. They are poor because they are not able to enforce their “entitlements”. Investment in human resources development is essential to enabling the poor to realize their entitlements and to develop their capabilities to take advantage of the opportunities offered by globalization.

(Adapted from the 12th Prem Bhatia Memorial Lecture on “Government in the 21st Century: Some Challenges of Governance and Democracy in India”.)