THE global order is in a flux. Leading world powers like the US, China and Russia are hedging their bets and working out strategic options in an environment beset by uncertainty. India too is carefully weighting alternatives, as it plays footsie with the US, tries to maintain its age-old friendship with Russia, and struggles to manage complex ties with China, the Asian dragon.

US President Donald Trump has turned the American policy on its head. The old certainties of a multilateral trade regime and liberal values of democracy and human rights are no longer sacrosanct. He walked out of the Paris Climate Accord, Trans-Pacific Partnership, UN Human Rights Council, and the Iran nuclear agreement. He is quibbling with NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organisation) for the latter to pay its dues and not rely on the US to foot the future defence bills for European security. Trump, a billionaire tycoon and a Reality TV star, is not an establishment man, and is bent on doing everything differently from his predecessor, Barack Obama, who is disliked by the former’s supporters. As a deal maker in business, Trump believes in bilateral, and not multilateral, negotiations.

During his election campaign, Trump raged against China for illegal trade practices, which hurt American businesses. He charged China with “raping” US interests, manipulating its currency to make exports more competitive. He promised to fix China.

The Sino-US balance of trade is in China’s favour, with the 2017 figures showing trade gap as high as $375 billion, according to figures published by the US Commerce Ministry. Taking this into account, Trump began a trade war with China. Both the US and China imposed tit-for-tat tariffs on $34 billion worth of goods in July. Washington is expected to increase tariffs on an additional $16 billion of Chinese goods, which the latter is likely to reciprocate with. Washington is talking of more pressure by additional levy of 25 per cent on Chinese imports worth $200 billion. China has warned of hiking tariffs on 5,207 items imported from the US, amounting to $60 billion. These wars can bring down the world economy.

The rise of Trump has to do with large sections feeling left out by the liberalised economy, which took American jobs out to nations like India and China, where labour is cheaper. The disillusionment was present before 2016. The world order, assiduously built by the victors of World War II, was crumbling. The Financial Crisis of 2008 sapped out the gains of the liberalised trade regime. Unfortunately, it made companies super-rich, but left large sections out of the wealth loop. The “Occupy Wall Street” movement, and Brexit vote, also a result of the fear of influx of refugees from Syria and other conflict zones, popularised protectionist sentiments. The election of the anti establishment Trump, over the liberal favourite, Hillary Clinton, was the culmination of this process.

“The world has entered a totally new era where the old order is teetering on the brink of disintegration while a fairer one is yet to firmly materialise. The change from Pax Americana to Pax Globalcana, a phrase I coined, will be prolonged and full of risks, requiring careful and cool-headed management by all major powers and an improved international framework, including a better global governance system. Today both are in the process of being worked out and no assurances of their success can be given,’’ He Yafei, former vice-minister in-charge of the overseas Chinese in the foreign ministry wrote in a special edition of Foreign Policy which focused on US-China ties.

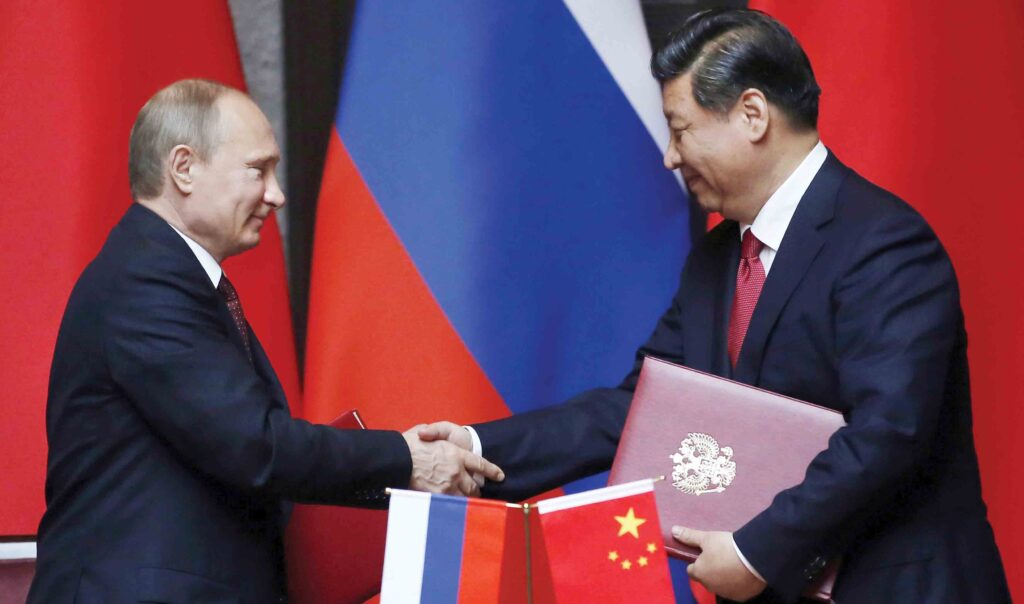

The key lies in the relationships between China and the US, Russia and the US, and among the other major and middle-level powers. These are evolving rapidly, and buffeted by headwinds of changes. So far there is no indication which system will replace the old. As Washington draws up its protectionist barriers and gets into sanction mode against Teheran and Moscow, Moscow and Beijing are forging a closer alliance. The process began earlier but is now firming up into a formidable force. The driving force behind the China and Russian ties is countering US’ geopolitical influence. For Russia, the theatre is in Europe and the Middle East; for China, it’s the South China Sea and Eastern Pacific.

IT was the expansion of NATO to the former Eastern bloc, the deployment of the US defence shield, the Velvet Revolution, which triggered the crisis in Ukraine. Moscow’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 was a reaction to the anti-Russian forces in Ukraine wanting to go with the US and West with hopes to join NATO. This, felt Russian Czar Vladimir Putin, was a direct threat to Russia, which did not want Western forces on what he considered was Moscow’s backyard. Crimea’s Sevastapool is home to Russia’s Baltic Fleet.

Following Crimea’s takeover, Moscow faced the wrath of the so-called free world. Sanctions were slapped on Russia. Moscow’s market for oil and gas dwindled. China with its ever-growing thirst for oil and gas saved the Russia’s economy by buying both oil and gas at “friendship” rates. China invested in Russia’s energy sectors, though the former was frustrated at the slow rate of progress of the pipeline deals. Moscow’s lower barriers made it easier for the Chinese investors. China also invested in Russian railways and telecom sectors. Financial cooperation between the two nations’ banks increased. Relations between the two former Communist powers have never been as good as they are now. During a visit to Moscow this April, the Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi said the links between the two countries at “the best level in history”.

US President Donald Trump has turned the American policy on its head. The old certainties of a multilateral trade regime and liberal values of democracy and human rights are no longer sacrosanct

The evolving global dynamics are at the heart of China-Russia relations, as Beijing trades war with Washington, and Moscow is being challenged in the Middle East, and Europe.

In the past, the Communist connections saw their ups and downs. Former Soviet Union and China were at one time brothers-in-arms. But China broke out, when the US President Richard Nixon and his Secretary of State Henry Kissinger decided to exploit the Russia-China tensions to cut the Soviet Union down to size during the Cold War era. China agreed, and the US helped with technology and business support. The Chinese economy took off, and never looked back. “China’s shift from the Soviet Union to the US is one of the most important geopolitical realities of the 1970s,” commented. Since then, things went through a full circle and today China and Russia have again found common grounds of cooperation.

China’s President Xi Jinping and Putin established close connect. The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) is their way to challenge NATO and the Western order. China-Russia trade, which initially comprised the energy sector expanded. In 2017, Russia-China trade was $87 billion. The aim is to reach $100 billion by the end of 2018. Between January and March this year, trade increased by 31 percent. Putin pointed out that “the supply of products with a high processing degree – machines, equipment, vehicles, increased. More than 70 priority projects worth over $20 billion are being implemented through the intergovernmental commission for investment cooperation.”

“The China-Russia trade space has previously been made up of energy deals,” said Chris Devonshire-Ellis, Founder and Chairman, Dezan Shira & Associates. However, he noted, “We are seeing an expansion of this into other commercial markets such as finance, IT, automotive, and machinery. China has also just signed a free trade agreement with the Eurasian Economic Union. This creates further business opportunities for companies in these sectors in both markets and is a welcome and overdue development. It is time for Russian companies to be looking at China and vice-versa.” Dezan Shira and Associates assists foreign investors in Asia, and has offices in both Russia and China.

THE China-Russia relation is regarded by Western analysts as a marriage of convenience. In fact, at China’s 19th Party Congress, which crowned Jinping as the Communist king, heading every institution in China for an indefinite period, a resurgent China harped back on the country’s glorious past. It said that it was ready to spread the Chinese way of doing things across the globe. However, the people-to-people contacts between China and Russia remain dismal. China with its economic clout combined with constructive engagement with the US is on top of its game. Russia remains the junior partner in the relations.

Moscow’s economy has been crippled by sanctions. Putin likes to call the shots, but is constrained by the circumstances. But now China needs Russia. Beijing, therefore, is keen to give weight to its ties with Russia. China is concerned about America’s global hegemony, and describes its relations with Russia as “comprehensive strategic partnership of coordination”.

Things, as usual, are not this simple. Apart from the fears Beijing has about the US’ aggressive interference in the former strategic interests in Asia, it is also scared of the US outreach to India, in its desire to counter China with India. The Asia Pacific region was renamed as Indo-Pacific, and this caysed more heartburns in China.

MEANWHILE, the Russia-US ties are almost the same as in the Cold War era. The American establishment hates Putin, with Democratic and Republican lawmakers having no qualms about calling him a thug. The liberal press in the US hates Putin’s guts. Since the evidence of Russian meddling in the 2016 presidential elections, Putin is in the dog house so far as the American press is concerned. But Trump is not with the establishment on this, as is his stance on other contentious issues. He has a fascination for the Russian strong man, and believes that engaging with Putin is a better idea than not doing so.

The American press is in no mood to see anything beyond the Russian meddling in the US elections, the human rights abuse, and the annexation of Crimea. Indignant American journalists agonise over Trump giving short shrift to the US intelligence agencies and preferring instead to believe Putin. Putin is no angel but working with Russia will be better for world peace than if the two nuclear powers worked at cross purposes. Despite opposition from all sides, Trump met Putin in Helsinki, but the details of the meeting have not been reported. Trump came in for fierce attacks after the joint news conference with Putin. But then, Trump is not a straightforward participant. Despite his fondness for Putin, he slapped sanctions on Russia, and pushed the latter closer to China.

For a while, after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1989 and end of the Cold War, the relations between a weak Russian Federation and the US seemed to take off. Boris Yeltsin, the earlier Russian Premier, was a favourite of the Western democracies. When Putin replaced Yeltsin in 2000, and promised to bring back Russia to its former global status, ties between Washington and Moscow remained on track. During George W Bush’s visit to Russia in May 2002, joint statements on a “new strategic” relationship were made and it was claimed that the two would enter into “a new age of friendly relations”.

That is history. Despite Trump’s wish to improve ties with Putin, the former will be tied down by domestic public opinion, US Congress, and the foreign policy establishment. “President Trump would like nothing more than to bring back the trophy of fixing US-Russia relations. Some cooperation, if in each country’s interest, can happen. Renewal of the New START nuclear arms control agreement, for example, could happen because each state has an interest in its extension. Still, a true reset across all issues is unlikely since American and Russian interests simply don’t align, and nothing is pushing either leader to the negotiating table. Undoubtedly Putin wants better relations too, but better relations would require just as many, if not more concessions from the Russian side than he could stomach,” explained Samuel Rebo of the Eurasia Group.

Yet, the US and Russia have worked together. In Syria, Russian intervention helped to clear large swathes of territory from the control of the terror group, ISIS, and various Sunni fundamentalist forces. Despite the US and Western antipathy for the Syrian President, Bashar al Asad, and substantial differences in policy and approach, Washington and Moscow were able to coordinate approaches and share information, when necessary. Can Trump reset the ties with Russia in the near future?

Where does India fit in this ebb and flow of international diplomacy?

India, if it plays its cards well, is in a position to expand its global footprints and play a significant role in global affairs. Since the days of the George Bush administration, Washington has been looking to Democratic India to counter Communist China. The India-US civil nuclear agreement of 2005 was a result of the strategic thinking of the neo-cons, who were an integral part of the Bush administration.

Bringing India out of its nuclear isolation was the first step. Washington wanted New Delhi to play a pivotal role in the Asian Pacific region, and expand its maritime presence in the Pacific, where China was being increasingly assertive. Despite considerable pressure, the previous UPA coalition government was unable to move entirely into the US orbit. It also did not wish to aggravate the already-testy ties with China. The former defence minister AK Antony kept twiddling his thumb on closer defence cooperation with the US.

When Hillary Clinton visited India as Obama’s Secretary of State, she said that the US was willing to help India’s emergence as a major power. But New Delhi had to share the responsibility, and not shy away from playing a more active role in the Asia-Pacific theatre. The American’s have wanted India to have joint patrols with the US navy in the Pacific. But even the Narendra Modi government, which is more inclined to play ball with the US, declined. In 2016, during the Delhi Dialogue, the US Pacific Command chief Admiral Harry B Harris said that India and US would soon begin joint patrols. The MEA denied it.

As Washington draws up its protectionist barriers and gets into sanction mode against Teheran and Moscow, Moscow and Beijing are forging a closer alliance…The driving force behind the China and Russian ties is countering US’ geopolitical influence. For Russia, the theatre is in Europe and the Middle East; for China, it’s the South China Sea and Eastern Pacific

Still, under Modi, India is less hesitant about defence cooperation with the US. During Modi’s visit to the US in June 2017, India was designated as a “major defence partner”. Although the two nations signed the crucial Defence Framework Agreement in 2005, India was in no hurry to sign the three foundation agreements necessary for the two defence forces to work together. In 2015, the Modi government renegotiated the Logistics Support Agreement, and signed in with a few changes. It was renamed the Logistics Exchange Memorandum of Agreement (LEMOA). This was the first of the foundation agreements.

THE agreement will allow both the militaries to use each others’ facilities for supplies and repairs. India made it known that this does not mean that the American military personnel will be stationed in the country. India is likely to sign the second foundation agreement called the Communications Compatability Security Agreement (COMCASA) by the end of this year. This will ensure a legal framework which enables the transfer of critical, secure, and encrypted communication between weapons platforms of the two countries.

Defence experts say that COMCASA is necessary for the Sea Guardian drones that India is keen on acquiring from the US, as these operate on a secure data and communication system link. This will leave only the Basic Exchange and Cooperation Agreement to be signed. Not everyone is happy about the foundation agreements as a few critics fear that this will make India dependent on the US. It will also gradually ensure that the Russian systems will be replaced by the American ones, as they are not designed for inter operability with American weapons and communication networks.

Washington is moving quickly to bring India into its fold, and gain strategic and commercial advantage. Last week, American Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross announced that the US will soon lift the export controls for high technology product sales to India. New Delhi wanted this for years. Once the measures kick in, India will have access to defence equipment, which the US gives to its NATO allies like Japan, South Korea, and Australia. It will open the doors for deeper defence cooperation. By placing India on the Strategic Trade Authorisation-1 list of countries, Wilbur Ross hopes that it will also benefit the US manufacturers.

THE move was welcomed by India’s ambassador to Washington, Navtej Sarna, “It is a sign of trust not only in the relationship but also on India’s capabilities as an economic and a security partner, because it also presupposes that India has the multilateral export control regime in place, which would allow the transfer of more sensitive defence technologies and dual use technologies to India and without the risk of any proliferation,” he said. India will be the only South Asian nation to be in this position to acquire such technologies.

The idea of a quadrilateral group of democratic countries – the US, Japan, Australia, and India – in the Asia-Pacific with a loose defence arrangement was an idea pushed by Japan’s Shinzo Abe in 2007. The first meeting towards this end was held in Manila. China vehemently protested, and saw it as an attempt to checkmate it. The move fizzled off when Abe lost power. The Labour government voted to power in Australia wanted cooperation with China.

Since then, the Chinese assertiveness in the South China and Eastern Pacific increased. China churned up the sands from the oceans to build on several islands and reefs to strengthen its defence. The Quad was revived in 2017, with the four countries engaging on building what Abe had earlier termed as the “arc of democracy” in the Pacific. The second meeting took place in April 2018. Now, the chances of the Quad to work together have doubled.

“The Quad is a symbolically and substantively important addition to an existing network of strategic and defense cooperation among four particularly capable democracies of the Indo-Pacific. What makes the Quad unique is that its members are powerful enough militarily and economically to resist various forms of Chinese coercion while offering the “muscle” necessary to defend the foundations of a Free and Open Indo-Pacific from potential challengers,” said Jeff M Smith of Heritage Foundation.

Washington is moving quickly to bring India into its fold, and gain strategic and commercial advantage. Last week, American Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross announced that the US will soon lift the export controls for high technology product sales to India. New Delhi wanted this for years

As Smith noted in 2007, India had virtually no US military hardware. Today, it hosts US surveillance and transport aircraft, attack helicopters, and is ready to induct drones into its defense system. Japan has amended its Constitution to allow for greater defense and security cooperation with the US. India and Australia are holding defense talks and exercises, and planning to work together closely. The time has come for the Quad to take firm roots. Other nations in East Asia are happy. Perhaps this is the key to Quad’s success.

Whatever may be the inhibitions about the US in certain sections of the Indian establishment, the fact remains that China has taken note of the growing warmth in India-US ties, and realises that India is being shored up as a balancing force. It is good to have the world’s only super power (maybe a declining power) as a friend. During last year’s stand-off on the India-China border over the building of a road in Bhutan, there was cynicism that Washington did not stand more firmly with New Delhi.

Trump and his whimsical nature is a problem for Modi. The bottom line is his unpredictability. This is why, though New Delhi is moving into the Washington sphere of influence, it does not wish to lose its strategic autonomy. In the last seven decades, India tried to maintain its neutrality between the US and Soviet Union (now Russia). It did not always succeed, drawing closer finally to the former Soviet camp. Today despite Trump’s outreach to Delhi, India wants to make sure it has plenty of options.

Repairing ties with China is one of them. The informal Wuhan summit between Modi and Jinping, did that. India and China both need a secure environment. So for the moment it suits both not to escalate tensions on the border. New Delhi and Moscow are old friends. Despite the US pressure on India to stall the purchase of Russia’s S-400 missile system, Modi stood firm. During the Modi-Putin informal summit in Sochi, which followed Wuhan, the Indian leader promised that India will not back off from the deal. Finally, Washington waived the sanctions on India for this particular deal.

New Delhi is again a member of the SCO. Together with Russia and China, it is also a part of the five-member emerging economic group, BRICS, which includes Brazil and South Africa. There is also a trilateral grouping of Russia, India and China. Modi is with Jinping and Putin in calling for the removal of protectionist barriers, on expanding and strengthening multilateral trade, climate change, and the importance of a UN driven world order. The trio wants to challenge the Western dominance of the financial institutions and supports the BRICS Development Bank which is the first step to challenge the World Bank and IMF.

Trump and his whimsical nature is a problem for Modi. The bottom line is his unpredictability. This is why, though New Delhi is moving into the Washington sphere of influence, it does not wish to lose its strategic autonomy. In the last seven decades, India tried to maintain its neutrality between the US and Soviet Union

YET when it comes to Jinping’s pet project, the Belt and Road initiative (BRI) and revival of the ancient maritime silk route, India is adamantly against it. The latter, like many in the US, fears that this is China’s ploy at expanding its economic and military might. Russia, dependent on the Chinese funds to revamp its ageing infrastructure, is an enthusiastic partner in BRI. So, New Delhi has kept its foot in both the camps, and will continue to straddle both the worlds till a clearer picture emerges.

As China’s He Yafei said, a new type of major power relations has to evolve. Without that the international order may well collapse. First and foremost should be collective efforts to strive for building the “new type of major power relations” based on the principle of “no confrontation, no conflict, mutual respect and win-win through cooperation,” he explained.

If this doesn’t happen, whatever may be the relative power equations and strengths of the various countries, the world will find it difficult to avoid the “Thucydides Trap”. Misunderstandings about each other’s actions and intentions can lead the modern nations to fall into a deadly trap first identified by the ancient Greek historian Thucydides. He explained, “It was the rise of Athens and the fear that this instilled in Sparta that made war (between the two) inevitable.” In the past five centuries, there were 16 cases in which a rising power threatened to displace a ruling one. Twelve of these ended in wars.