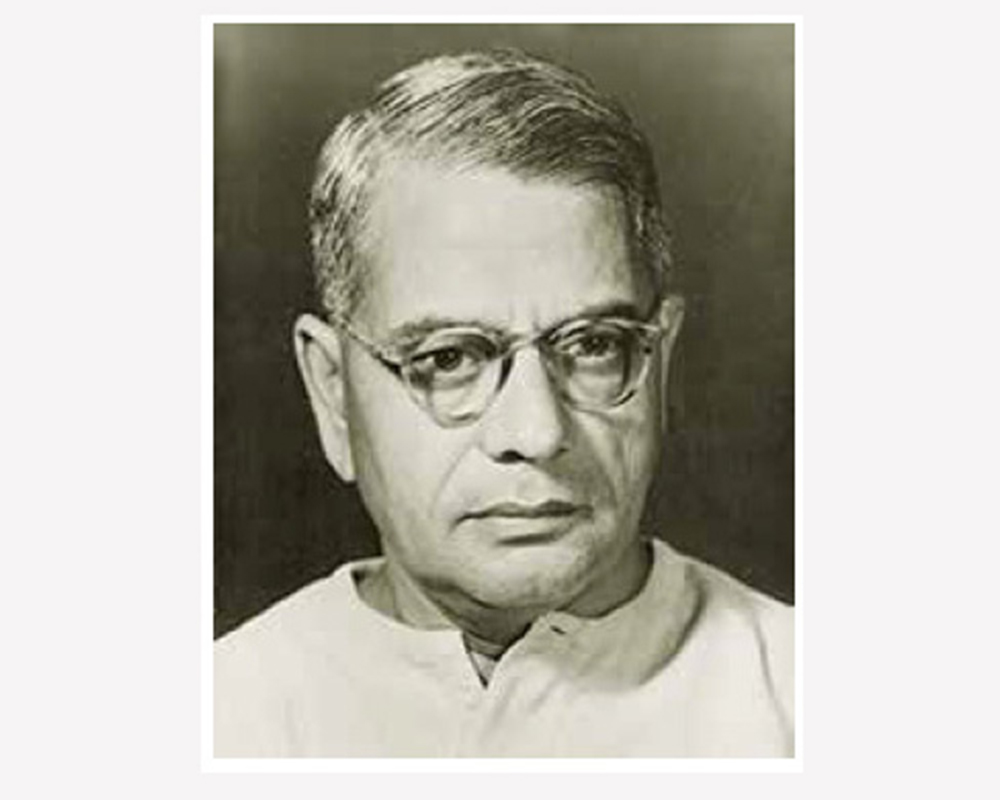

IT started with a follow-up question that politicians ask after a newspaper or news channel report. On September 4, 1957, a Lok Sabha member of the ruling Congress regime, Ram Subhag Singh, referred to an article that appeared in The Statesman a month ago, and asked Finance Minister Tiruvellore Thattai Krishnamachari (TTK) for details. The newspaper said that the recently-nationalised Life Insurance Corporation (LIC) invested Rs. 10 million “in a private enterprise with its headquarters in Kanpur”.

The FM’s answer was an unequivocal ‘No’. On November 29, Singh asked another question on the issue. He was armed with more ammunition this time, and the Deputy Finance Minister, Bali Ram Bhagat, acknowledged that in June 1957 LIC bought shares worth Rs. 12.69 million in firms that were connected to Haridas Mundhra. This was the truth. But Bhagat lied in his answers to the supplementary questions, which were lobbed like hand grenades by Feroze Gandhi, another Congressman and Nehru’s son-in-law.

According to the Chagla Commission, the first to investigate the scam, Bhagat deliberately gave false information. He said that LIC’s decision was “dictated” by its Investment Committee, and that the “Government had no hand in the purchases”. He added that LIC was guided by returns and safety, and didn’t operate to favour an individual or business group. Since it owned shares in Mundhra concerns, it increased them as it was “able to purchase them at that time at an advantageous price”. Bhagat maintained that LIC wasn’t interested in the stock markets, but only in its investments.

Over the next few months, Feroze Gandhi exposed the falsehoods. His information was correct as was evident from the reports of the Chagla Commission and Bose Committee. The decision was dictated, not by LIC, but by Finance Secretary HM Patel, with the complete knowledge of his boss, FM TTK. The RBI Governor HVR Iyengar, and PC Bhattacharyya, Chairman, State Bank of India (SBI), were in the loop. LIC Chairman CR Kamat and Managing Director, LS Vaidyanathan, merely followed the “orders”.

Contrary to Bhagat’s answers, the government later claimed that the decision was aimed to resolve the crisis in the Calcutta Stock Exchange, and shore up the falling share prices. This too was a blatant lie, and Chagla Commission charged that the only ostensible objective was to help Mundhra to wriggle out of his personal crises at LIC’s expense. The shares were bought through a private deal with a scandalous businessman, whose shadowy past was known to the finance ministry, RBI, and LIC. The insurance firm paid higher prices for the shares, whose values diminished over the next several months.

As we shall later flesh out, during and after the scandal, Prime Minister Jawahar Lal Nehru continued to support TTK, and even maligned the Chagla Commission. The FM tried to wriggle out by contending that he had merely asked Patel, Finance Secretary, to “look” into the matter, and blamed a leading business house for hurling mud at him. Patel implicated his boss and, according to a RBI report, “insisted that TTK, Iyengar (RBI), and Bhattacharyya (SBI)… shared equal responsibility”. LIC’s officials said that they merely followed the orders of their bosses.

Although TTK resigned on February 18, 1958, a few days after the Chagla Commission indicted him, he was rehabilitated by Nehru in 1962 as a minister without a post, and later as FM. An inquiry under the All-India Services (Discipline and Appeal) Rules, 1955, asked for the removal of Patel, the chief orchestrator, and compulsory retirement of LIC’s Kamat. Both were overturned by the Union Public Service Commission (UPSC), which exonerated the finance secretary, and recommended Kamat’s censure.

LIC-Mundhra Affair

The sequence of the events began on June 18, 1957, when TTK addressed a meeting of businessmen and financiers in Calcutta. Present at the meeting were Pstel, Iyengar, and Bhattacharyya. On June 21, when both TTK and Patel were in Bombay, Mundhra met the latter with a proposal to “sell or mortgage some of his assets (shares in group companies)” in off-market deals to prevent open sales that would affect the prices of the shares. Obviously, Mundhra hinted that a selling pressure would further depress the stock markets.

ON the same day, the businessman wrote a letter to Patel with the details. Mundhra wanted LIC to buy Rs. 8 million worth of shares from him and his brokers, and another Rs. 3-4 million from the open market. His second proposal was that LIC could loan him Rs. 10 million and, in lieu, he would give business worth the same amount to the insurance firm. The businessman also listed his liabilities— Rs. 52.4 million, of which Rs. 39.3 million were owed to banks and Rs. 13.1 million to his brokers. The money was required to settle the accounts of the brokers, and prevent a selling wave by them.

Patel met LIC’s Kamat on June 22, and the latter agreed to the buying of the shares. The next day, a Sunday, Patel, Kamat, and Bhattacharyya met Mundhra, who was asked to make definite proposals. The purchases of the various shares worth Rs. 12.69 million were confirmed on June 24 and 25. LIC had earlier purchased stocks of Mundhra concerns in March and April of 1957, as also later in September the same year. But the June deals comprised the largest investment made by LIC in a single business group.

As the Chagla Commission found, the prices favoured Mundhra’s brokers, and were at LIC’s expense. The reason: the deals were concluded on the closing quotations of June 24, a Monday, which allowed opportunities to manipulate prices. This was evident from the price movements on June 24—of both the ordinary and preference shares of the six concerned companies, i.e. 12 different kinds of shares, only one fell between June 21, a Friday, when the market was open, and June 24, when it reopened after the weekend.

According to the Chagla Commission, the first to investigate the scam, (Bali Ram) Bhagat deliberately gave false information. He said that LIC’s decision was “dictated” by its Investment Committee, and that the “Government had no hand in the purchases”

The rises were huge—41 per cent in the case of the ordinary share of The Osler Electric Lamp Manufacturing, 34 per cent in the case of the preference share of Richardson & Cruddas, 25 per cent in the case of preference share of The Osler Electric Lamp Manufacturing, and 20 per cent in the case of the ordinary share of Angelo Brothers. The prices paid by the LIC were higher than what even Mundhra had asked for in his proposals.

More importantly, the prices fell substantially over the next few months. Although the stock market declined between June 24, 1957, and January 16, 1958, the tumbles in Mundhra’s concerns were higher. For example, blue chips like Tata Iron & Steel, Indian Iron & Steel, and ACC were down by 1.5, 2.9 and 5.1, respectively. “As against this, the depreciation in the value of BIC (British India) is 34.33, Osler Electric 49.33, Richardson & Cruddas ordinary 51.50 and in preference 32.50”, said the Chagla Commission report.

In addition, there was an undue haste in pushing through the deals, bypassing LIC’s Investment Committee, which was told of them much later. While questioning the “propriety” of the transactions, M.C. Chagla observed, “I could not help feeling as I was listening to the evidence that there was a sense of urgency about this transaction. The transaction was negotiated and effected by hurried meetings held in the Reserve Bank of India while Mr. Patel was busy with more important questions of public importance.”

Mundhra’s shadowy past

To understand why everything was done in a great hurry, one has to explore the business life and times of Haridas Mundhra, which was comprehensively done by a RBI report and Chagla Commission. Chagla dubs him as a “flamboyant personality” and a “financial adventurer”, who was “suspected to be a law-breaker and possessed a doubtful financial reputation and whose antecedents were of a most questionable character”. His ambition was to “build an industrial empire by dubious methods” and “he is not very particular about the means he employs so long s the end is achieved”.

According to the RBI, Mundhra had “virtually no education” and started from scratch. But within a few years in the 1950s, he built a “formidable industrial empire”, largely through high-profile takeovers. He initially bought Osler Electric, and then purchased controlling stakes in Richardson & Cruddas, Jessop & Company, and British India. Mundhra’s modus operandi was simple, and was one that was followed by hundreds of global and Indian takeover artistes, both before and after his spectacular rise, and dismal fall.

LIKE others, Mundhra would drum up the share prices of his companies through extensive purchases, mortgage them to get loans from the banks, and then use them to affect new takeovers, and push up their stock prices too. It was a self-fulfilling and self-financing cycle. A secret RBI report (February 1956) sent by its Deputy Governor, Ram Nath, to the central government revealed this comprehensively. He paid Rs. 10-12 per share to buy British India, propelled the price to Rs. 14, and mortgaged the shares to the banks at a collateral price of Rs. 11 a share. Thus, he managed to “finance the takeover almost entirely from borrowed funds”.

By May 1957, Mundhra had borrowed Rs. 156 million from the banks, and mortgaged shares worth 75 per cent of the share capital in three concerns, and 50 per cent in five other companies. To increase his access to funds, the businessman was known to mortgage and sell duplicates, triplicates, and quadruplicates of the same shares. Two banks told the RBI in November 1957 that they possessed duplicates of British India, and Richardson & Cruddas. One of them, said the RBI report, “discovered to its discomfiture” that Mundhra “had pledged two sets of shares bearing the same serial numbers, neither of which was authentic, with two of its branches”.

This form of fraud could have continued had the prices of the concerns remained high, or continued northwards. But, by end-1956, Mundhra was in a bind. His bank borrowings were high, and stock prices fell sharply. He bought more shares through brokers, who too were financed by the banks, but with limited success. “Nor could he, for want of necessary resources, take delivery from the brokers”, who demanded higher margin calls, which is a percentage of the prices of stocks paid by the buyer to postpone deliveries.

Blame the system, not individuals

LIC was Mundhra’s saviour of the last resort. If the cash-rich insurance firm could loan him the money, or buy the shares parked with the brokers, he could come unscathed out of the crisis. If he sold them in the open market, the prices would plunge due to the large orders, he would incur huge losses. Hence, the critical need for off-market deals, and a false justification that the motive was save the Calcutta Stock Exchange, not Mundhra.

Both TTK and Patel furthered Mundhra’s argument that the transactions were to deal with “drag effect” on the exchange, which would have pulled down the market if the shares were sold openly, and hurt the investors. However, this wasn’t the case. The Chagla Commission argued that the “ordinary investor had practically lost all interest in the Mundhra concerns” by June 1957. This was because the public has “an uncanny instinct of scenting trouble and of knowing that all is not well with some concerns”.

“Therefore, in removing this so-called drag and raising the prices of the Mundhra shares, the Corporation (LIC) was not in any way helping the general investing public. It was not seeking to cure any general malaise that affected the market,” added the report. Although the general prices on the Calcutta Stock Exchange declined between August 1956 and June 1957, the brokers’ reports didn’t indicate a looming crisis or a Mundhra drag. Hence, the only aim was to help Mundhra and his brokers ride out their personal crises.

Apart from the standard ruse to either blame the system, or justify the act to correct it, there was the usual game to pass on the blame and buck. As the Vivian Bose Committee, the second one formed to investigate the matter, said, “We found some of the highest-ranking officials of the land shirking responsibility and hiding the truth. We found each other trying to wash his hand of a matter that has evoked much public criticism and each trying to throw the blame on the other.”

It added, “The Minister blames the Principal Finance Secretary and the Secretary blames the Minister and a colleague (LIC Chairman) who holds a high office; the colleague shifts the onus to a co-worker, the Managing Director of a large national institution in which both hold high and responsible office and the Managing Director, in turn blames each of the others. All these gentlemen and a Governor of the Reserve Bank, as well as the Chairman of the State Bank of India give differing and mutually contradictory versions of the same incident. Men of standing in the business world give us childish explanations to cover up something of which they are either frightened or ashamed.

The report concluded, “We have not been told the whole truth.”

Need to help a fraudster

Possibly, there was reason to partially hide the truth. But before we come to that one needs to emphasise that the leading actors in the scandal, especially those in the finance ministry, RBI, and LIC, knew about Mundhra’s murky business details by June 1957. This was proved through documents presented by Rajya Sabha members during the debates in the house in February 1958 and September 1959, as well as evidence given to the various committees. Hence, it was clear that LIC was not investing in the blue chips, or the best of the best, but possibly in companies known for their shenanigans.

Ironically, TTK was among the first to red flag the businessman. When he was Minister of Commerce and Industry, he wrote a letter to then FM, CD Deshmukh, in August 1955. “It seems very strange that despite so many stringent measures in the Companies Act right at our very nose HD Mundhra can do what he likes,” it said. The letter added, “I do think that we must have some reserve powers for the Government at least to secure information and to prevent mischief when a large block of shares of any company whose capital and assets are more than Rs. 20 lakh are to change hands.”

Chagla dubs him (Mundhra) as a “flamboyant personality” and a “financial adventurer”, who was “suspected to be a law-breaker and possessed a doubtful financial reputation and whose antecedents were of a most questionable character”. His ambition was to “build an industrial empire by dubious methods” and “he is not very particular about the means he employs so long the

end is achieved”

Later, in February 1956, the then RBI Governor, Rama Rau, wrote to Patel (Finance Secretary) questioning Mundhra’s activities, which included “breaches of foreign exchange regulations and his rapid acquisition of controlling interest in large industrial concerns”. There was the secret RBI note mentioned earlier. The next month, in another letter to Patel, Rau enclosed a copy of a preliminary RBI report related to the “manipulations in the accounts of the associated concerns of Mundhra”.

On September 19, 1957, before the scandal erupted, Nehru questioned Mundhra’s character. In the absence of TTK, Nehru was acting as the FM when papers related to Mundhra were presented to him. “So far as I know, the reputation of this gentleman is not good,” noted the PM. Even LIC was aware of the forged shares of Mundhra’s concerns. In its June deals, it tried to protect itself against the possible deliveries of duplicates or triplicates. Only it made the fraudster the chowkidar. LIC put the onus on Mundhra to deliver genuine shares, or make good the difference. The Chagla Commission found this bewildering that a dubious seller was given this responsibility.

THE above details beg the relevant questions. Why did TTK change his tune in less than two years? Why did Nehru not intervene? And why did LIC went ahead with the deals? The Bose Commission provided a plausible answer. Mundhra had recently donated Rs. 250,000 to the Congress Party. Rajya Sabha members revealed that when the workers of the Mundhra-owned Kanpur Cotton Mills “were going to strike”, leading Congressmen like Morarji Desai and Manubhai Shah intervened in the matter.

In long conversations with Mundhra at Shah’s residence and office, the two politicians convinced Mundhra not to shut down the company. The reason, according to the duo, was that elections were around the corner, and the closure could “have an adverse (electoral) impact on the Party”. Mundhra took the decision despite the fact that he was losing Rs. 25 lakh a year on the Kanpur Cotton Mills. The LIC deal was probably a quid pro quo.

However, the UPSC concluded that there was no ground for such an inference. The political donations and the decision to keep the mill running did not place the government “under any obligation – express or implied – to enter into a transaction with him (Mundhra) of the order of over a crore of rupees”.

Protect the guilty campaign

Whatever might be the reservations that Nehru had about Mundhra, the PM went out of his way to protect his FM, TTK. In his autobiography, Roses in December, Chagla mentioned a few pertinent points. At a dinner, the then Home Minister, Gobind Ballabh Pant, asked Chagla to head the one-man commission. While they were still taking, TTK entered, and was told by Pant that Chagla had accepted to head the inquiry. “I could see from TTK’s expression that he did not welcome the idea at all – either he did not like the inquiry, or did not like my being the person to conduct it,” wrote Chagla.

From the beginning, Chagla was clear that his inquiry would be open to public. The reasons: “The public was entitled to know on what evidence any particular decision was based”, and that “justice should never be cloistered, but should be administered in full view of the public”. Since it was the first mega scam in Independent India, or possibly because the FM was involved, there was a huge public interest in the inquiry. Thousands attended, and thousands waited outside. Newspapers were full of daily reports.

“One day the crowd was so large and became so unruly that it looked like they would storm their way into the office. The Police Commissioner decided on his own to install a loudspeaker outside the office so that the people would hear all that was being said,” wrote Chagla. In the afternoon, when he came to know about it, Chagla asked the Police Commissioner not to treat the proceedings as a “theatrical performance”. The loudspeaker was removed.

The same day, or soon thereafter, at a public meeting in Bombay, Nehru made a pointed and sarcastic remark about the loudspeaker. Although he accepted Chagla’s explanation later, Nehru paid a “high compliment” to TTK at a meeting at the Indian Merchants’ Chamber. “I cannot help remarking that it was hardly proper, when a judicial inquiry was being held involving the conduct of a Minister, for the Prime Minister to pay that very Minister a compliment in public,” wrote Chagla.

Since it was the first mega scam in Independent India, or possibly because the FM was involved, there was a huge public interest in the inquiry. Thousands attended, and thousands waited outside. Newspapers were full of daily reports

AFTER the Chagla Commission report was presented, Nehru wrote to TTK, “So far as you are concerned, I am myself convinced that your part in this matter was of the smallest and that you did not even know much of what was done.” The PM dubbed the report as a “rather one-sided presentation of facts”. Once TTK resigned, Nehru added in Parliament, “I am really sad that one of our esteemed colleagues, of keen intellect, outstanding ability and mental vigour, should be absent from the House and the country should have been deprived of his services.” As mentioned earlier, TTK was rehabilitated as FM.

Post script: In conclusion, one needs to ironical fate of Feroze Gandhi, who was instrumental in exposing the scandal. It was his investigations that led to the nationalization of private insurance companies in 1956. Gandhi exposed how leading industrialists, especially the combined Dalmia-Jain Group, used the insurance firms as cash cows. The owners would give purchase orders to brokers; if there was a profit, it was booked by them, and the losses were loaded on to the companies’ books. Post nationalization, in just over a year, Gandhi highlighted how the government too could do the same – it too could benefit private businessman at the expense of the insurance company. Tragically, Gandhi was criticized by several politicians, who felt that the nationalization move had resulted in the LIC-Mundhra scam.

Alam Srinivas is a business journalist with almost four decades of experience and has written for the Times of India, bbc.com, India Today, Outlook, and San Jose Mercury News. He has written Storms in the Sea Wind, IPL and Inside Story, Women of Vision (Nine Business Leaders in Conversation with Alam Srinivas),Cricket Czars: Two Men Who Changed the Gentleman's Game, The Indian Consumer: One Billion Myths, One Billion Realities . He can be reached at editor@gfilesindia.com