IT is often, but wrongly, assumed that India’s first Prime Minister, Jawahar Lal Nehru, was against the private sector. This wasn’t true, at least in the first seven years of his rule. As he once said, “I have no shadow of doubt that if we say ‘lop off the private sector’, we cannot replace it…. Therefore, you must not only permit the private sector but, I say, encourage it in its own field.” Nehru’s beliefs can be gauged from two of his initial decisions.

As soon as he became the PM, Nehru opted for a mixed economy, not socialisation, as was laid out in what was popularly dubbed as the Bombay Plan (1944-45). Although the document did not reflect the views of all the Indian industrialists, it was prepared by leading ones such as JRD Tata (Tata Group; Bombay), GD Birla (Birla Group, Calcutta), Kasturbhai Lalbhai (Lalbhai Group; Ahmedabad), and Shri Ram (DCM Group; Delhi).

Hence, it laid down an economic vision of what a powerful section of the business community desired. Nehru followed it, almost to the ‘T’. One needs to remember here that most of the signatories to the Bombay Plan, especially Tata, Birla, and Lalbhai, were close to the national leaders, funded the freedom movement, and worked with the politicians to shape pre-Independence policies. This unofficial, but public, partnership continued.

Nehru’s first Five-Year Plan (1951-56) was based on the idea of a mixed economy, in which the private sector had an equivalent role to play compared to the public sector. According to Medha Kudaisya, a business historian, the proposed investments during the period were divided in a 60:40 ratio – 60 per cent by the public sector, and the remaining by private enterprises. The actual investments during the five years were in a ratio of 52:48.

What’s more important is that under the first Five-Year Plan, only a miniscule six per cent of the public funds was reserved for industry. In effect, the capitalists drove manufacturing growth, and the government focussed on other areas such as agriculture, irrigation, and social services, which together comprised 54 per cent of the investments, as well as transport and communication (27 per cent), and power (13 per cent).

Only in 1954, after his visit to China, did Nehru change tracks, and turned completely socialistic. Henceforth, only the public sector was involved in mega projects, even as curbs were imposed on private entrepreneurs. Over the next two decades, this mindset, which was aggressively pursued by Nehru’s daughter, Indira Gandhi, evolved into the Licence-Permit-Quota Raj. On paper, everything that the private did, or didn’t do, was controlled.

Unfortunately, either deliberately or by default, the restrictions only enhanced the economic power of the businessmen. Between the 1950s and 1970s, several business families became near-monopolies in various sectors. Of the 100 products listed in the Report of the Monopolies Inquiry Commission (1965), almost two-thirds were marked ‘H’, i.e. with a high degree of concentration. A monopolistic regime was visible in eight products, and oligopolistic trends, i.e. two or three firms had 100 per cent market share, in 26 others.

Of the 75 powerful and largest business groups mentioned in the same report, the Tata and Birla Groups were the largest with total asset base of more than `400 crore, and almost `300 crore, respectively. The combined asset base of the 75 groups worked out to 46.9 per cent of “all non-government and non-banking companies”. Thus, 75 families and private professionals controlled almost half the assets of the entire private sector.

Several factors contributed to the economic concentration. Two business historians, Dwinjendra Tripathi and Jyoti Jumani, concluded that the licensing system to check the expansion of large business enterprises was “heavily weighted in favour of large houses, because being better informed and organised they could jump the queue and thus pre-empt others”. Hence, they cornered licences, which they either used to gain dominant positions, or didn’t use them but prevented the entry of competitors.

IN addition, only large business houses had the international contacts to access new technology, and ink foreign partnerships. Hence, they could both enter new sectors, and keep up with the innovations in existing areas. The 1965 report stated that “the presence of a foreign collaborator of repute weighs with the licensing authorities, and this… gives an edge to the big man” in further cornering of the industrial licences..

Before the nationalisation of the banks in 1969, most were owned by private groups. The 1965 Inquiry Commission maintained that the larger business groups gained an “unfair advantage” to get loans because they had their “own men” in the board of directors of the private sector banks. This was confirmed by the Reserve Bank of India, which agreed that there were “instances where considerable advances have been made by certain big banks on concessional terms to concerns in which the directors were interested”.

But the worst part of the regime was the expansion of corruption. According to Tripathi and Jumani, “perhaps the most pernicious, though unintended, by-product of the system of controls was widespread corruption in bureaucracy. For, in the absence of clarity in criteria and guidelines, government officials at almost every level had a field day obliging the applicants, both deserving and undeserving, in exchange for illegal gratifications”.

Most people think that Indira Gandhi was more socialistic than her father given her policies to nationalise banks, curb foreign exchange, and introduce the draconian Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practice (MRTP) Act. However, the fact remains that India’s third PM wasn’t interested in controlling the power of the private sector. She only wished to strangle the “Syndicate”, a group of Congress politicians that controlled the money bags required to fight elections and retain political power.

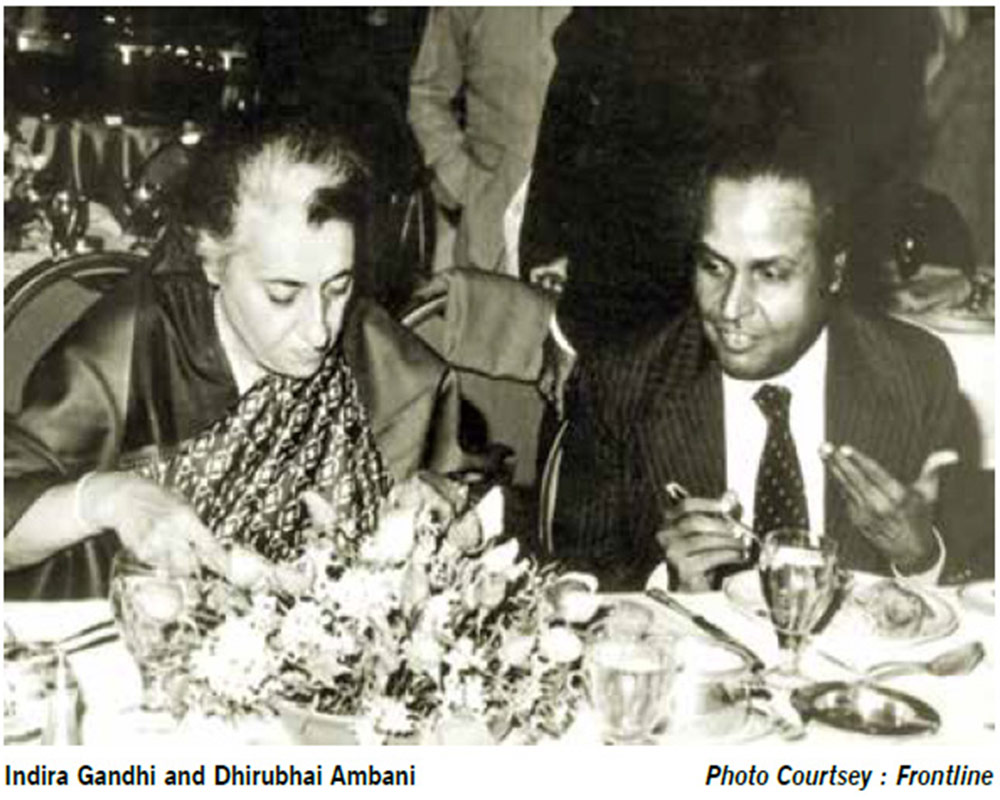

Gandhi’s decisions were, thereby, driven by the desire to squeeze the existing large business houses, which supported the Syndicate, and create a new base of loyal entrepreneurs, who would fund her political ambitions. Bank nationalisation gave the govern-ment the tools to decide which businessmen would thrive, and which barely survive. The Foreign Exchange Regulation Act and MRTP Act tightened the licensing regime.

Hence, unlike in the 1950s and 1960s, new business groups emerged in the next two decades. These grew rapidly, and quickly acquired the same status as the older business empires of Tata and Birla. Some of them, like the House of Ambani, became both financially and politically powerful. Hence, cronyism continued, and corruption became systemic. Over time, by this century, corruption pervaded the political and economic systems.

This trend was aided and abetted by the ban on political donations in 1969. According to an article (2015) by E Sridharan and Milan Vaishnav, the ban “eliminated the most important legal source of election funds. Without providing an alternative financing mechanism, such as state funding, Gandhi’s decision—far from abolishing the link between business and politics— effectively pushed campaign finance underground. Today, it’s an open secret that the opaque funding of elections represents the single-biggest driver of political corruption and criminality in India”.

IN his 1987 paper, Stanley A Kocha-nek dubbed this as the expansion of “briefcase politics” in India. As political funding became illegal, until the changes in recent times, the business-political nexus became dishonest, and accelerated cronyism. According to Kochanek, the Congress, and other governments too, became “sensitive and responsive to the large variety of pressures and demands” from groups based on “language, religion, region, and caste”. He added, “One of the most vocal and organised of these functional, class-based interests has been the Indian business community.”

Several political commentators like Prem Shankar Jha felt that the motive was not to “secure above-board source of (political) funds in the future, but to cut off the flow of funds to its (political) rivals”. It was true that Indira Gandhi was “alarmed” by increasing financing of opposition right-wing parties like the Swantantra Party and Jan Sangh. But most pundits don’t realise that the real challenger to the Congress Supremo was, well, the Congress.

In 1966, Indira Gandhi was appointed as the PM by the Syndicate, which considered her a puppet, or Gungi Gudiya. The pressures on her multiplied after the election debacle in 1967, when the Congress received the lowest seats in Lok Sabha and lowest vote share since 1952, and half of Indira’s earlier cabinet ministers lost. The internal rivalry exploded during the 1969 presidential elections, when the Syndicate nominated N Sanjeeva Reddy, a staunch opponent of the PM, as the official Congress candidate.

Architects of the Bombay Plan

Angered, and with her back to the wall, the PM retaliated and propped up an independent candidate, VV Giri, the then Vice President. Despite the official whip issued by the Congress to order the Congress MPs to support Reddy, Indira Gandhi appealed for a “conscience vote’ (Antaratma ki Awaaz). The backdoor shenanigans enabled the independent candidate, Giri, to defeat the official Congress candidate, Reddy. The internal battle was out in the open. The Congress Party expelled Indira Gandhi, which led to a split.

Somehow, the new Congress, led by Indira Gandhi, remained in power with the support from Left parties. In the 1971 elections, she came back to power with a thumping majority – 352 out of 518 seats, or 68 per cent majority in the Lok Sabha. The ban on political donations was to demolish the old Congress’ and Syndicate’s money bags. By making such funding illegal, Indira Gandhi could easily initiate extreme actions against her Congress rivals.

Nehru’s first Five-Year Plan (1951-56) was based on the idea of a mixed economy, in which the private sector had an equivalent role to play compared to the public sector. According to Medha Kudaisya, a business historian, the proposed investments during the period were divided in a 60:40 ratio – 60 per cent by the public sector, and the remaining by private enterprises

As Sridharan and Vaishnav observed, “As a result, the ban created a financial vacuum that was filled with black money, institution-alising a corrupt equilibrium in which politicians (read: Indira Gandhi and her coterie, initially) allocated licences necessary to operate in an increasingly dirigiste economy in exchange for under-the-table ‘donations’.” The end result: the control of a dishonest and corrupt economic system over political governance.

Fortunately, the rotten system had unintended consequences. It led, bizarrely, to the making of Indian MNCs. Since the older business houses weren’t allowed to expand or grow in India, they sought alternative attractive options. They went abroad, and invested across the globe, especially in East Asia. They became global players. One of the foremost among them was Aditya Birla, who was later dubbed as India’s first global entrepreneur.

Beginning in the late 1960s, and during the 1970s, Birla expanded in Indonesia, Thailand and Vietnam, where there were growing opportunities due to economic reforms and the respective nations’ attempts to woo foreign capital. It was a win-win situation for Birla. First, it allowed the group to use its free capital more profitably. Second, it entered the new Asian markets that were about to boom. Finally, it escaped the clutches of the Indian bureaucracy, and received a red-carpet welcome in the other nations.

In a speech in the 1970s, Aditya Birla of the Birla Group, narrated an incident related to one of his companies, Gwalior Rayon, which made viscose staple fibre. The company was not allowed to expand its capacity in India, but was permitted to set up a joint venture in Thailand. Birla explained the ironic effects of the MRTP restrictions: “India… is today importing from our own joint venture plant. Strange indeed are the ways of the Government….”

As Birla explained in another speech to his business colleagued, “You will be surprised to know the kind of incentives that have been given for our latest joint venture in carbon black in Thailand. They are so keen to industrialise the country that they asked us what kind of incentives we require for putting up the plant. Being an Indian, I had no dearth of suggestions. A list of 32 points was given to them. To my utter surprise, on some of the points on which I had never dreamt of getting approvals, they agreed.”

The incentives included exemptions of the various taxes and royalty payments, duty-free imports of raw materials, three-fold increase in duty on future imports of carbon black, and no local competition for five years. Birla said, “Believe me, I would not have asked for more.”

However, there were problems on how to finance the equity in these joint ventures (JVs) abroad. Thanks to FERA, the Indian business houses were not allowed to invest in their overseas ventures. So, Birla financed a part of the equity in kind – through the exports of machinery from India to the foreign projects. To fund the rest, he roped in non-resident Indian (NRI) friends to become part-owners in the various foreign ventures.

Several factors contributed to the economic concentration. Two business historians, Dwinjendra Tripathi and Jyoti Jumani, concluded that the licensing system to check the expansion of large business enterprises was “heavily weighted in favour of large houses, because being better informed and organised they could jump the queue and thus pre-empt others”

Through these routes, according to a chapter in the Oxford Indian Anthology of Business History, Birla “launched a global presence that would, in 1997, comprise dozens of factories and trading offices in 23 countries outside India with a combined annual turnover of $3 billion”. The group furiously expanded under Aditya’s son, Kumar Mangalam, who took over the reins in 1995, when he was 28. In the over two decades since then, the group’s turnover, according to the group’s website, went up from $2 billion to over $44 billion.

Alam Srinivas is a business journalist with almost four decades of experience and has written for the Times of India, bbc.com, India Today, Outlook, and San Jose Mercury News. He has written Storms in the Sea Wind, IPL and Inside Story, Women of Vision (Nine Business Leaders in Conversation with Alam Srinivas),Cricket Czars: Two Men Who Changed the Gentleman's Game, The Indian Consumer: One Billion Myths, One Billion Realities . He can be reached at editor@gfilesindia.com