IN the early 1960s, the Indian Administrative Service (IAS) had a halo around it, thanks to the legacy of the British Raj that had put it in the elite category. And, for students of St. Stephen’s College in Delhi, a top educational institution, the civil services examination was considered a natural choice. Therefore, the decision of Ravindra Shankar Mathur, a Chemistry (Honours) graduate from the college, to attempt the civil services exam was not surprising.

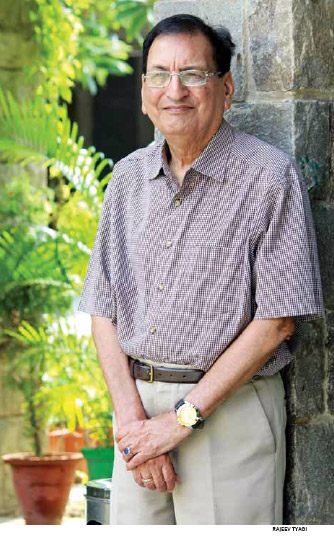

“IAS was considered top of the league,” recounts Mathur, 73 years of age today. His family had migrated to Delhi from Amritsar after OCM (Oriental Carpets Manufacturers), a fabric company which employed his father, downed its shutters in the late 1950s. He claims to have appeared for five papers, three more than what was prescribed for the Indian Police Service (IPS). Besides the IAS, the Indian Foreign Service (IFS) and the IPS, the IAS examination (as the civil services examination was called then) also selected officers for central services, including Indian Railways and the income tax service. Mathur cleared the exam in his second attempt. The 1965-batch IAS officer was allocated Uttar Pradesh, a cadre considered good in those days.

IAS officers in the collectorates had the entire district administration at their beck and call. Mathur initially slept in a retiring room at a railway station, did not have a vehicle and travelled in trains, rickshaws and by bike during his first posting as Sub-Divisional Magistrate (SDM) in Amroha. Yet, every time he would go out, a fourth-class official with bells fastened to a stick would clear the traffic for him. “I would travel in a rickshaw and the official would walk in front, tolling the bells and shouting ‘SDM aa rahen hain’, to make way for me,” he reminisces. At that time, IAS officers also had the luxury of hunting black partridge, which was not an endangered species then.

Once in a while, Mathur got to travel in a ‘VIP’ jeep allocated to him by RK Kaul, the then District Magistrate in Moradabad. Though the jeep was reserved for ferrying VIPs during their visit to Moradabad district, the DM off and on allocated it to his IAS subordinates. It was in an extremely rundown condition. Mathur would hold its gear even as his driver manoeuvred through the traffic. “The gear would shift to neutral if it was not hand-held,” Mathur recalls with a smile.

During his 35-year career, Mathur served as SDM in Amroha, Karwi and Lakhimpur Kheri, Joint Director (Industries), District Magistrate (DM) in Meerut and Aligarh, and Chief Secretary in Uttar Pradesh, Secretary (Food), (Statistics and Programme Implementation), Director-General (Central Statistical Organisation) and Chairman and Managing Director at Hindustan Insecticides Limited at the Centre.

‘Civil’ servant

Mathur says the biggest take-away from his career was the civility and respect with which the political class treated him in Uttar Pradesh and New Delhi. They never interfered in his work and allowed him to do his job, he says, adding that he learnt not to grumble and act in accordance with what was provided to him.

In particular, the former IAS recollects his stint as DM in Meerut when the Janata Party government ruled at the Centre after Emergency. Meerut was the home district of the then Union Home Minister, Chaudhary Charan Singh. “Certain activist student leaders were taking advantage of the Janata Party’s overemphasis on democracy and freedom. They would demand money from shopkeepers. Once I was driving through a market and found them extorting money from a chemist. We ordered a lathicharge and arrested around 50 students,” he recalls. Mathur later explained the situation to Singh. “He listened to me and commented ‘Kiya toh theek hai’, with a chuckle,” he remembers.

Mathur says people in Meerut would flaunt their relations with Singh. One day a person approached him for a favour, saying that he was Singh’s nephew. He asked the person to wait outside and phoned the Home Minister. “Girftar hua ki nahin (Have you arrested him or not)?” Singh asked him after hearing about the person. The ‘nephew’ overheard the telephone conversation and decamped without meeting the DM.

Mathur says the political class of the 1980s and 1990s accorded great respect to bureaucrats. He cites an incident which happened when he was the Registrar (Cooperative Societies) in Lucknow. “I was sitting with minister Vasudeva Singh, when a person stormed into the room and handed him a piece of paper over my head, saying ‘Registrar se kara dena’ (get it done by the Registrar),” he recalls. Vasudeva Singh lost his cool and before asking the person to get out, shouted, “Even I call him Registrar sahib. How dare you speak like this?”

Mathur worked as Secretary to chief ministers Narain Dutt Tiwari and Vir Bahadur Singh. He distinctly remembers that the two always made sure that the state Chief Secretary’s (CS) position was not compromised in any way. “They would never overrule the CS on file and simply wrote ‘please discuss’ if they did not agree with the latter,” he claims.

Two CMs and a CS

IN 1998, when Mathur rose to be the Chief Secretary in the state, an unprecedented situation arose. The then State Governor, Romesh Bhandari, sacked Kalyan Singh and swore in Jagdambika Pal as the new Chief Minister. For around 72 hours before a floor test in the Assembly determined which of the CMs enjoyed the confidence of the legislature, both Singh and Pal claimed to be CM. Mathur would get calls from both of them. The matter was resolved with the floor test, but not before Mathur became the only state Chief Secretary in Indian history who reported to two CMs at the same time.

Mathur retired in 2001 after serving as Secretary (Food and Statistics and Programme Implementation) and in other important positions in New Delhi. Father of two daughters—an assistant professor in Lady Shri Ram (LSR) college and a consultant on governance, respectively—he plans to write a book on the unsavoury two-CM incident.