FORTY-FIVE minutes after one of the largest branches of the State Bank of India at New Delhi’s Parliament Street opened on May 24, 1971, a Monday, the chief cashier, Ved Prakash Malhotra, received a shocking request. A call from PN Haksar, Principal Secretary, Indira Gandhi, Prime Minister, asked him to pay Rs. 6 million (worth more than Rs. 230 million in 2019) to someone who was waiting nearby. According to Malhotra, when he demurred, the PM came on the line, and gave the orders. “Yes, Mataji,” was the cashier meek reply.

Malhotra immediately asked the deputy chief cashier, Ram Prakash Batra, to pack the amount. When he signed on the branch’s register, the deputy head cashier, Rawal Singh, asked Batra for a payment voucher, and was told it would be signed by Malhotra. The cash-filled trunk was loaded on to a car, which was driven by the chief cashier. Outside a church not too far away, he met a tall, burly, fair-complexioned man, Rustam Sohrab Nagarwala (aged 50), a Parsi. The latter spoke the pre-arranged code word, “Bangladesh ka Babu”. To which, Malhotra, as instructed, replied, “Bar-in-law”.

Nagarwala sat in the car, and got dropped off at a taxi stand at the junction of Sardar Patel Marg and Panchsheel Marg. He took the cash box, and asked Malhotra to go to Indira’s house to collect the cash voucher. The SBI official went to the PM’s house, and couldn’t find her. He couldn’t contact her at Parliament House. Worried, he went to Haksar, who told him that no such instructions were given, and he should report the robbery to the police. Within hours, the normally inept and inefficient Delhi Police solved the case.

At 9.45 PM, the police told journalists that it had arrested Nagarwala, and recovered the money, except for the petty expenses incurred by the cuprit during the day. The news was splashed on the front pages of the newspapers the next day, May 25. It caught the imagination of the public, as the details of the incredible story came out. Years after the robbery, the Janata government, which came to power in 1977 after the Emergency was over, appointed the Reddy Commission to inquire into the issue. Decades later, it formed a powerful sub-plot in Ronhinton Mistry’s novel, Such a Long Journey.

However, what this crime proved the most was Indira Gandhi’s “immense authority”. As Gyan Prakash wrote in Emergency Chronicles, “Her very name could magically unlock bank vaults.” The same was true for India’s tryst with the ‘People’s Car’, whose main protagonist was Sanjay Gandhi, the younger son of Indira Gandhi. In a case of extreme nepotism and crony capitalism, the PM unabashedly gave the project to her son, who had neither the experience nor ability to manufacture an indigenous and cheap car, Maruti.

Today, Sanjay is remembered for his extra-constitutional authority, and ability to order ministers, senior politicians, central and state secretaries, and senior police officers during the Emergency years. But, between 1968 and 1980 (when Sanjay died in a plane crash), the Maruti saga epitomised how blasé India’s First Family was about corruption, and how all rules and laws could be bent to benefit a family member. It was a kind of centralisation of corruption that had never been seen before.

Let’s first analyse the Nagarwala case to understand the contours of concentration of corruption at the top of the governance hierarchy. No one believed the thief’s initial claim that he stole the money on a whim to highlight the Bangladesh’s cause. This was because of several reasons. Nagarwala was convicted within a few days. The trial, the fastest in Indian judiciary’s history, was over in 10 minutes. The only evidence presented was his confession. No other supporting or corroborative evidence was sought. Nagarwala was sent to prison for four years, and fined Rs. 1,000.

Then, two of the main protagonists in the case died in mysterious circumstances. In November 1971, the young DK Kashyap, Assistant Superintendent of Police, who led the team for” Operation Toofan (Storm)” to nab the robber, died in a car accident on the way to his honeymoon. On March 2, 1972, on his 51st birthday, Nagarwala died of cardiac arrest, less than two weeks after he was transferred from the Tihar Jail hospital to GB Pant Hospital. This was after he claimed that he would expose powerful individuals, and wanted to be interviewed by DF Karaka, Editor, Current, and “an acknowledged leader of the Parsi community”.

Janata government-appointed Reddy Commission found that at least on one occasion in 1967, Nagarwala met Indira and Haksar. He wanted the PM to use secret information he had about the ongoing Vietnam War between the US and Communist rebels to broker peace. Both Indira and Haksar denied the meeting, but written records proved it. There were reports that Malhotra, SBI branch’s chief cashier, knew the thief and, in fact, had handed cash in similar circumstances to him, and several

other people.

More importantly, it wasn’t Malhotra who went to the police. It was the frightened and concerned Rawal Singh, deputy head cashier, who did it when he didn’t hear from Malhotra for hours, and was worried that he didn’t possess a signed voucher for the cash withdrawal. This forced the police to act, as also publicised the matter. There was also the issue as to why Nagarwala confessed if he knew Malhotra and Indira.

Now the narrative goes in the realm for half-truths and speculation. One version says that the Rs. 6 million was part of the PM’s secret and personal slush fund, which was deposited in several bank accounts. This was routinely used for purposes dictated by her, and this had been done before. The coterie in the Prime Minister’s House, including Haksar, were responsible for handling this money. Chief cashiers like Malhotra were in the loop, and had done this before on several occasions. This is why he confidently went in search of the PM to collect the payment voucher.

The second version is telling, even revealing. According to an article in India Today (April 30, 1977), there was a larger plot related to security, diplomacy, and geopolitics. Nagarwala, a former army person, was an active agent of India’s external intelligence agency, Research & Analysis Wing (RAW). He was involved in money transfers by RAW to Bangladesh’s Mukti Bahini, a rebel group that aimed to secede from Pakistan. Indira was involved in the game plan, which had progressed well by May 1971.

“In May 1971, the Government of India had realised that the war with Pakistan on the Bangladesh issue was inevitable. Training camps to train Mukti Bahini volunteers had been set up all over the country particularly along the borders with what was then East Pakistan. In May, Tiger Siddiqui, the 21-year-old guerrilla leader from Mymensingh had brought 10,000 of his boys for training…. They needed arms and ammunition and that needed money,” said the piece in India Today.

Nagarwala was one of RAW’s most trusted cash couriers. He was ordered to collect the Rs. 6 million and fly to Calcutta. SBI’s Malhotra was the only officer in the branch to handle these Bangladesh-related secret funds. “It is because of the association with the intelligence agencies and trustworthiness that he was simultaneously put on the Prime Minister’s Relief Fund Committee,” said the India Today report. This is possibly why Malhotra went to the PM’s office and Parliament to collect the Nagarwala-related voucher.

Despite the rumours, the Reddy Commission failed to reach specific conclusions. In response to the troubling questions that remained on the table, Justice Reddy had this to say, “To supply an answer to these would force me to leave the safe haven of facts which are required to be established by evidence and enter the realm of conjecture and speculation.” But he did comment on the ‘efficiency’ of the police, which moved with undue haste, more to protect the image of the Prime Minister than to arrive at the truth.

Unfortunately, in the Sanjay-Maruti affair, Indira’s image went for a toss. The scandal provided tonnes of additional fuel to the burning cries that her government was the most corrupt. It gave ammunition to JP (Jayaprakash Narayan) movement, which was a major reason behind the Emergency declaration. In Bihar, Gujarat, and other states, large sections of students, professionals, and middle class protested against Indira’s regime for its corruption, dishonesty, inefficiency, and lack of governance.

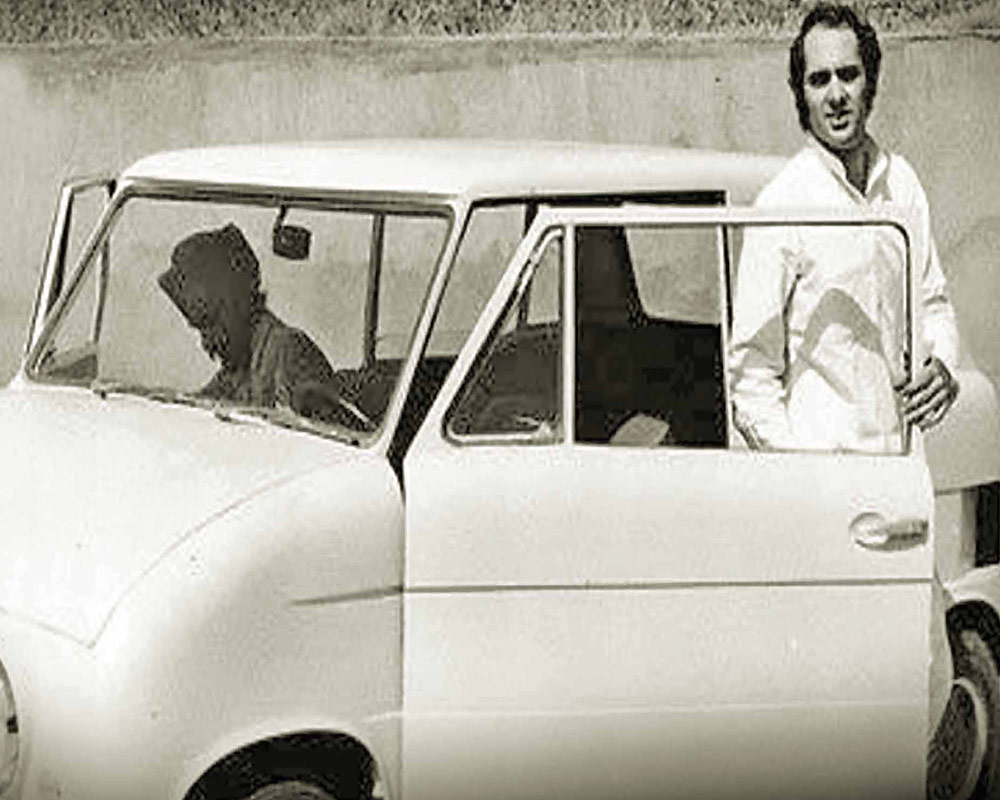

Sanjay’s rendezvous with a car started when he was six. His grandfather and India’s first PM, Jawahar Lal Nehru, gifted him a pedal car. When he was 14, he announced that he was going to make a car. As a teenager, he and his friends would whisk away “unlocked cars for wild rides, and then dump them when the fuel got over. At least once, this led to an embarrassment because of an accident, which became a police case. In The Sanjay Story, Vinod Mehta said that the younger son of Indira drove around in an “ancient derelict car”, and experimented with jeeps, Land Rovers, Ambassadors, and Fiats.

In the mid-1960s, Sanjay trooped off to Crewe (England) for an apprenticeship with the renowned car-maker, Rolls Royce. One isn’t sure whether he completed it. Some commentators said that he got “an ordinary National Certificate in Mechanical Engineering”, and others claimed that he left it mid-way. But quite early in the apprenticeship, he was bored. In 1966, Indira wrote to Haksar, who was then the Deputy High Commissioner in London that her son had learnt all Rolls Royce had to offer, and urged him to find something for her “lonely” son.

Rolls Royce too had misgivings, and, in 1967, told Haksar, now the High Commissioner, that any further time spent by Sanjay would be “mutually unprofitable”. The same year, the prodigal son returned. He set about to build the country’s first small car, one that was so cheap that it could be purchased by the masses. Two people helped the political heir-apparent to design the car—Arjan Arjan Das, a puncture-wallah with an amazing knowledge of cars, and Capt Tillu, an instructor at the Delhi Flying Club.

What this crime (Nagarwala case) proved the most was Indira Gandhi’s “immense authority”. As Gyan Prakash wrote in Emergency Chronicles, “Her very name could magically unlock bank vaults.” The same was true for India’s tryst with the ‘People’s Car’, whose main protagonist was Sanjay Gandhi, the younger son of Indira Gandhi

Elder brother Rajiv introduced Das to Sanjay, who met Tillu as flying was his second (or was it the first?) passion. Together, the trio worked 24/7 at a shed in Gulabi Bagh (North Delhi), and later in Moti Nagar (West Delhi) within the premises of the well-known Sylvania Laxman factory. According to Gyan Prakash, “Amid the shanty workshops swarming with motor mechanics,” he assembled a prototype. Suddenly, the small car project, which had stalled, stuttered, and sputtered for almost two decades, gathered momentum.

Mysteriously, in August 1968, a copy each of Sanjay’s car proposal reached the Ministry of Industry and Planning Commission (now NITI Aayog). Within weeks, there were glowing reports about his prototype in the newspapers. On September 21, the Statesman gloated that he had achieved it against several odds and scepticism, even from his mother when he left for the Rolls Royce’s apprenticeship. On October 7, the Hindustan Times wrote how he had worked from 8 am to 8 pm every day to “assemble a small car with local parts”.

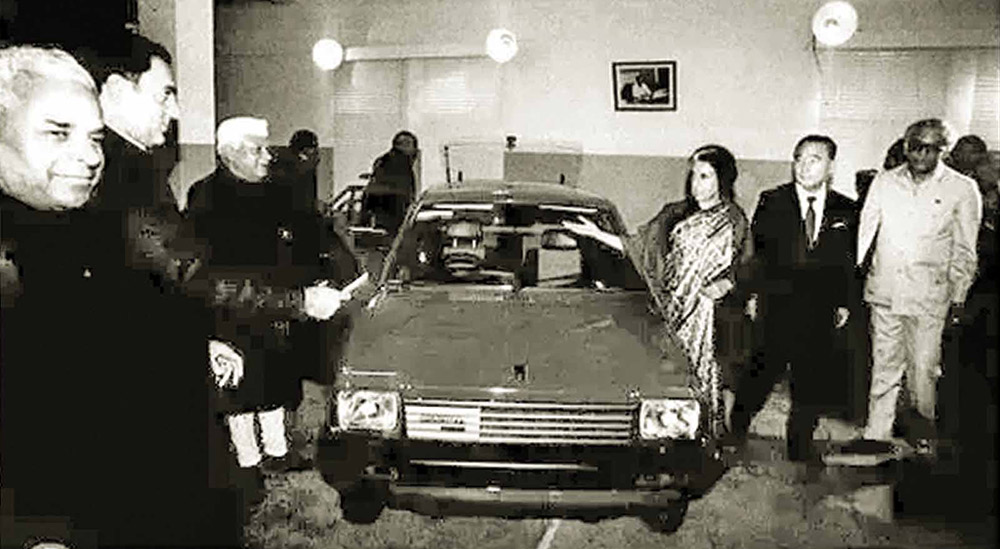

Twenty months after Sanjay applied for a car licence, the Cabinet, headed by Indira, approved it on August 7, 1970. The policy makers asked the relevant ministry to consider all the existing proposals for car manufacture in the private sector, which were based on “completely indigenous design and content”. They also said that the government maintained the right to establish capacity in the public sector. Only two of the existing 10 private proposals fit the bill—Sanjay’s and that of Madras-based M Mohan Rao.

Political opponents lashed against Indira and Sanjay. Jyotirmoy Basu, a Communist politician, dubbed it as a case of ‘nepotism’. Madhu Limaye, a socialist, called it ‘naked corruption’. Atal Bihari Vajpayee of the Jan Sangh (later BJP) said that it reflected ‘corruption unlimited’. Others maintained that it was a ‘boon’ to the PM’s son, and ‘blackmail’. The RSS-backed Organiser front paged the news in its August 22, 1970, issue. The headline screamed: “Indira Allots Baby Car Project to Son Sanjay”. It informed the readers, “So the baby has got the baby car and mom is happy”.

There was justification in the criticism. For two decades, various committees pondered on the small car issue, and concluded that it was an item of conspicuous consumption. The country’s scarce foreign exchange, especially after the 1956-57 crisis should be used to make “machines that build machines”, and not on elitist products like cars. As late as the mid-1960s, the government rejected a proposal by French Renault, selected by the Pande Committee, as it considered “small passenger cars a low priority”. Indira Gandhi publicly supported her son after the Cabinet decision. She said, “My son is a delicate young man, and with whatever money and energy he has, he has modelled a car, not a posh one, but one fairly comfortable and suitable for Indian conditions… my son has shown enterprise and I could not say no to him… If he is not encouraged, how can I ask other young men to take risks?”

Expectedly, Mohan Rao’s proposal was a non-starter, and got bogged down in bureaucratic delays. Only Sanjay was left in the fray. His car was named Maruti, after the son of the God of Wind. With such blessings, what could go wrong. Only one thing—the younger son of the Prime Minister had little clue on how to design a car, forget about how to produce it indigenously. But he went about it flouting rules, and laws, and bulldozing industrialists, state governments, and state-owned banks to fund the project.

Let’s begin with the car first. Years later, the AC Gupta Committee, which investigated the Maruti scandal during the Janata regime, found several smaller scams within the larger scandal. Initially, Sanjay tried to stall the mandated tests on the prototype by the Vehicle Research Development Establishment (VRDE), a research agency under the defence ministry. When such moves failed, Sanjay did send a prototype in early 1974.

Then Indira lost the national elections in 1977. When she returned in January 1980, the younger son tried to revive the Maruti project, and this time seek foreign collaboration. But his untimely death in June 1980 shattered his initiatives, and forever ended his dream

In a shock, the Gupta Committee noted, “But the whole indigenous car came (to the VRDE) with an imported engine. This was contrary to the rules, which mandated an indigenous engine.” Sanjay was either trying to fool the VRDE, or he possibly thought that it either wouldn’t notice or let it pass deliberately. A German national, WHF Muller, who was employed by Maruti as a consultant, imported two German engines as part of his ‘personal baggage’. Maruti paid the customs duties and additional fines as imports of engines were banned. One of them was used in the prototype that was sent to the VRDE.

In March 1974, the VRDE submitted its first interim report, which reported several defects in the prototype—stiff steering, brake failure, breakage of propeller shaft, and vehicle pulling to the right. In its second interim report, sent on May 4, 1974, the VRDE still wasn’t satisfied with the performance. However, the industry ministry deemed the prototype’s performance as “quite satisfactory”. Sanjay’s file was cleared the same day, and Sanjay’s letter of intent was converted into an industrial licence.

Reporting on the prototype (November 1972), the American newspaper, Washington Post, commented that it would not take a Ralph Nader (leading proponent of safety in cars in the US) to identify the short-comings of the “wispy feather-weight” Maruti. “His permit to build the car had been granted by the Ministry of Industrial development. It should have been given by the Ministry of Family Planning because when Maruti hits the road, it will become an unintended population control device.”

Maruti’s list of shareholders and directors made for an interesting read. They included, among others, leading industrialists such as Raunaq Singh of Apollo Tyres, Charanjit Singh of Pure Drinks (Campa Cola), VP Mohan of Mohan Meakin (Old Monk rum), MA Chidambaram of Southern Petrochemicals, and Sagar Suri (real estate and auto dealerships). The surnames of some investors were Misra or Jha. The Misras were related to a known politician, LN Misra, and the Jhas to his wife. They included the mother, brothers, aunts, cousins, nephews, and grandnephews from both the sides of the family.

Without blinking his eyelids, the Haryana Chief Minister, Bansi Lal, announced that his state was willing to provide land, electricity, and money for the project. Immediately, the state’s Town and Country Planning officials rezoned lands classified as rural to industrial. Haryana was prepared to buy 25% of Maruti’s share capital, and treat sales tax as interest-free loans to be repaid instalments five years after the commencement of production. The price of the land was to be paid in 18 instalments, after a 10 per cent down-payment. Land acquisition was completed in a flurry. Only a day, July 10, 1971, was fixed to entertain objections from the original owners. By 1 pm on the day, the hearings were finished; by 5 pm, compensations were announced. Cheques were issued immediately, and the Haryana officials went to the Prime Minister’s House with a draft agreement on August 9. When the Air Force opposed the acquisition because the location was close to its airfield and ammunition depot, the depot was moved.

Gyan wrote in his book, “In addition to gouging the dealers, Sanjay set his sights on two nationalized banks, Punjab National Bank and Central Bank of India, for loans to finance his company. By 1974, he had secured over 10 million rupees in bank loans, nearly half of which were unsecured.” This wasn’t it. Reluctant and opposing chairmen were shifted. Gyan said that in early 1974, Indira overruled PN Dhar, her Principal Secretary, and appointed DV Taneja, Sanjay’s friend, as Central Bank’s chairman.

Sadly in 1975, Taneja felt that he couldn’t overstretch his bank to fund never-sending loan demands from his mentor. “Sanjay was furious…. When his (Taneja’s) term came up for renewal in March 1975, the Prime Minister noted in his file that there were a lot of complaints against Taneja and that his term should be extended by a month. On May 1, 1975, the government appointed another chairman.” May be Taneja didn’t get the message.

The Emergency Years took Sanjay onto another route—a political path that was ridden with more power, more corruption, and more destruction of governance. Then Indira lost the national elections in 1977. When she returned in January 1980, the younger son tried to revive the Maruti project, and this time seek foreign collaboration. But his untimely death in June 1980 shattered his initiatives, and forever ended his dream.

Post Script: Maruti was named after a son of a God. How could it die a premature death? After Sanjay’s death, Indira pursued the project. Thus was born Maruti 800, the iconic car that unleashed the first waves of liberalisation and economic reforms in the country, and transformed the Indian society into a consumerist one. Brands, especially foreign brands, became the flavour of the times as Indians pursued conspicuous consumption like never before. “For the middle class, Maruti 800 was the fourth addition to the great Indian dream—Roti, Kapda, Makaan and Meri Maruti (Food, Clothing, Shelter, and My Maruti),’ said an article in the Economic Times (December 2008).

The success emboldened Indira’s elder son and the next Prime Minister, Rajiv Gandhi (in power between 1984-89), who was involved in the 800 projects after Sanjay’s death, to allow similar joint ventures in areas that ranged from automobile to computer. These projects slowly accelerated the reforms’ process, which moved at really high speeds in the early 1990s. But the seeds of the process were sown a decade ago, in the early 1980s.

According to Gyan, “Its (Maruti) story shows how a crony capitalist project served as an instrument for breaking through the crisis in the postcolonial economy of planning and national self-reliance.” It was an “opening shot” to kill the “administrative and economic norms that had governed postcolonial India.” It was beginning of the end of “Nehruvian ideal of planning and self-reliance” and it freed up the economy for “consumer capitalism”.

Alam Srinivas is a business journalist with almost four decades of experience and has written for the Times of India, bbc.com, India Today, Outlook, and San Jose Mercury News. He has written Storms in the Sea Wind, IPL and Inside Story, Women of Vision (Nine Business Leaders in Conversation with Alam Srinivas),Cricket Czars: Two Men Who Changed the Gentleman's Game, The Indian Consumer: One Billion Myths, One Billion Realities . He can be reached at editor@gfilesindia.com