AJAY Jain and Saurabh Jain regret the day they decided to shift their textile industry from Jind (Haryana) to Greater Noida (Uttar Pradesh). Unlike Haryana, where they bribed inspectors of 10 different departments—industries, labour, ESI, PF, sales tax, fire and safety, pollution, excise, weight and measurement, and electricity—systematically, in Greater Noida the demands are arbitrary.

For instance, in Jind they paid a specific amount to the labour enforcement officer through their industry association every quarter and had the Deputy Labour Commissioner playing mediator in case of a dispute between an industrialist and an enforcement officer. In Greater Noida, the gratification demands by the officer have no pattern and no moderator. Moreover, unlike Haryana, where the sales tax regulations are not very stringent, in Uttar Pradesh it is nearly impossible for a businessman to transport machines without paying a hefty bribe to tax sleuths.

Whereas in Haryana the rate for sales tax annual assessment is Rs. 1,500, in Uttar Pradesh an industrialist has to cough up around 20 times more. In Haryana, agents for pollution certification can procure a no-objection certificate (NoC) for an annual fee of Rs. 10,000, in Greater Noida even a low-level official from the State pollution department can seal the factory in case his gratification demands are not met.

In Haryana, the fire and safety inspector insists on installation of fire extinguishers made by a manufacturer who pays him a commission, in UP the Jain brothers need to get an NoC from the fire department for a price. Since the law and order situation in UP is pretty bad, there is also the possibility of criminals ordering them to sell their scrap to a particular company and to hire vehicles of a particular transporter only.

Bribing of various inspectors is a uniform feature from Kashmir to Kanyakumari. India’s exchequer may be losing at least a few thousand crores to such corruption annually

In case they wish to take the legal route to set up their unit in Greater Noida, it will take at least six months. Or, they can get a sales tax number and excise clearance and start production, greasing the palms of the rest whenever they turn up for inspections.

“Who will wait for six months to complete the formalities? Wouldn’t it be wiser to do production in that period?” Saurabh, the elder of the two, asks with a shrug. Monudeep Banerjee, a manufacturer of returnable packaging and the Jains’ neighbour, who is in the process of shifting his unit from Gurgaon to Greater Noida, endorses the statement.

Rob exchequer to pay rogues

What brings the Jains and Banerjee to western Uttar Pradesh are the property prices which have been on a downward curve in the last half-decade. They also anticipate evading all their taxes in league with corrupt state government machinery. This is what brought Govind Kumar, a paint shade printer, from Rajasthan to Greater Noida.

“Yahan saree earning sirf aapki hai (here the earnings belong to you alone), provided you pay a fraction of it in bribes. The rent is negligible and power supply is good,” Kumar, who employs less than half-a-dozen workers in his unit, notes. Being a small unit, he escapes the labour, ESI and PF dragnet.

Sales tax savagery

But Kumar often gets on the wrong side of the sales tax department. In such situations, his most preferable mantra is to quietly pay the quoted price: “Either pay what is demanded, or forget about the consignment,” he says. Kumar cites the example of a Delhi-based Japanese printer manufacturer, who he bought a printer from, to buttress his point. The manufacturer charged Rs. 2.78 lakh for the printer from him, but ended up paying around Rs. 2 lakh to Noida sales tax officials in penalty because the delivery from its warehouse near Indira Gandhi Airport was late by two days.

Unlike Haryana, Rajasthan and other States where you can transport a consignment anywhere on the basis of the invoice, in UP the receiver and sender are required to fill in the truck number, driver’s name, licence number and other sundry details. In case the vehicle changes on the way (it always does on long routes) and the driver and consignee fail to convey the same to the sales tax office, they will get into a soup. For a consignment worth Rs. 1 lakh, the bribe rate in the sales tax is Rs. 10,000 (10 per cent). But for something less costly (say, Rs. 45,000), it may go up to even 50 per cent of the cost.

Kumar also has before him the example of his neighbour, a paint manufacturer. The latter’s premises were sealed after he refused to cough up a few lakhs for a State pollution inspector.

Licence for corruption

Yet Kumar is lucky. He does not have to face a labour enforcement officer, who is considered to be the biggest threat to the industry. The officer, according to the Factories Act, 1948, can inspect any place with his assistants or experts and seize documents, take measurements and photographs. His only constraint under the law is that he has to operate within the local limits for which he is appointed. The officer has the licence to enquire about almost anything under the sun.

But his biggest weapons are the Industrial Disputes Act, Bonus Act, Overtime Act, Gratuity Act, Minimum Wages Act and a host of other laws, any violations of which are considered criminal acts and can lead to issuance of a non-bailable warrant against the factory manager/managing director. He teams up with workers’ unions to extort bribes from factory owners.

“He is the real naak ka baal (thorn in the flesh). He turns up at any odd hour, invents excuses (contract workers, height of a washroom, age of worker, exposed electric wires, absence of fire buckets, service conditions, and so on) and seeks gratification,” a member of the Association of Greater Noida Industries (AGNI), claims. Since small- and medium-size units can hardly afford to fulfil all provisions of the law, they pay him every month. The officer reports to the Deputy Labour Commissioner (DLC) appointed in every district. The DLC reports to the Labour Commissioner. The latter, in turn, reports to the Chief Labour Commissioner (CLC) headquartered in New Delhi.

THE Labour Enforcement Officer (LEO) has to keep the entire chain in good humour (deliver cash packets)—right up to the bureaucrats and politicians—to maintain a plum posting. He not only takes bribes in cash and kind (gold bangles, diamond earrings), but often pushes his own favourites into recruitment. A few labour officers even own or control the transport system and have a say in the award of different contracts in factories (like the sale of scrap). “The inspection system is an insidious disease. It is like black money—all pervasive but not visible in the open,” says Michael Dias, Secretary, the Employers Association, Delhi.

Dias, also a lawyer, accuses the government machinery of treating businessmen like criminals. “Captains of industry make the economy grow. They are treated shabbily. Laws have been created to frighten and extort money from them,” Dias fumes.

PP Mitra, Officer on Special Duty (OSD) in the Union Labour Ministry, who currently holds the charge of the Chief Labour Commissioner, was unavailable for comments.

No escape

There is no escape route. If an industrialist somehow manages to save himself from the labour enforcement machinery (including clerical staff), the possibility is he will be hauled by the company registrar office, Director of Factories, pollution control boards, ESI, PF, sales tax, fire and safety, electricity, excise (applicable in case a unit manufactures for the open market), and weight and measurement departments.

The last nine have their own set of inspectors. “Licences are sold for as much as Rs. 25 lakh. Besides, one also has to pay bribes for their renewal,” claims Aditya Gildiyal, Secretary, AGNI. Ajay Jain discloses industrialists in Jind pay monthly bribes to linesmen to ensure that they have access to uninterrupted power even if villages and cities remain dark. Dias says bribing of various inspectors is a uniform feature from Kashmir to Kanyakumari. The exchequer may be losing at least a few thousand crore rupees to such corruption every year. “It is a fairly realistic figure, though it may be difficult to quantify the exact amount. In every State, the inspectors have their rate lists. Only packaging changes with the government. The essence remains,” Dias notes.

Modi messiah

Dias and Gildiyal hope that the slew of labour reforms announced by Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the proposed amendments to the Factories Act, 1948, Apprentices Act, 1961 and Labour Laws Act, 1988, will deliver a knockout punch to the inspector raj.

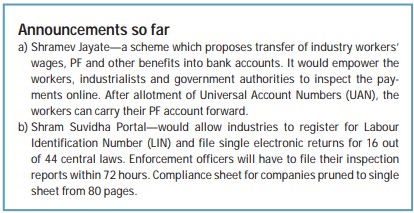

SHRAMEV Jayate, a scheme unveiled by Modi in October 2014, promises protection to manufacturing units against selective inspections, digitisation and portability of provident fund accounts through allotment of Universal Account Numbers (UAN) to industry workers. Under the scheme, a unique Labour Identification Number (LIN) will be allotted to each unit and, once it registers on the Shram Suvidha Portal, it will be in a position to file self-certified single online return for 16 out of 44 central labour laws.

After digitisation, it will be mandatory for the labour enforcement officers to conduct inspections on the basis of a computer lottery and file inspection reports within 72 hours of the inspection. Modi has promised to cut down the compliance sheet for the companies from the present 80 pages to a single sheet.

Ashok K Sharma, Associate Vice-President (Human Resources) in Moser Baer, hopes the States will implement the measures announced by the Prime Minister. He is sure the measures will prove to be oxygen for small- and medium-size industries. “The scheme will bring about transparency, speed and connectivity and erase mistrust between employers and employees. It will lead to a positive environment,” Sharma says. Gildiyal, who also handles human resources in Case New Holland, the multinational manufacturing tractors in Greater Noida, agrees with Sharma. Even Dias hopes to see better times in the evening of his life.

Recently, Anup Chandra Pandey, Joint Secretary in the Union Ministry of Labour and Employment, informed Dias that the government has drafted ‘the Small Factories and other Establishments (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Services) Bill, 2014’, to simplify the labour laws. Among other things, the draft Bill proposes to make the inspector a guide rather than a prosecutor and take small factories out of the ambit of existing labour laws. The Bill prescribes one register and has provisions for e-working and electronic returns. Once the Bill becomes law, the payment of wages to the workers will be done directly into their bank accounts. Moreover, it would allow a cluster of small factories to set up common facilities.

Shramev Jayate promises protection to manufacturing units against selective inspections and portability of provident fund accounts through allotment of Universal Account Numbers to industry workers

Proposals plethora

Apart from bringing in flexibility in employment, the Modi government wishes to introduce single registration for all labour laws, cut down registration time to a single day from 27 days, provide electricity connections quickly, ease up property registration, overhaul tax systems and make vocational training demand-driven by handing over Industrial Training Institutions (ITIs) to local companies.

The Prime Minister hopes to improve India’s standing in the World Bank’s ‘ease of doing business’ (currently placed at 142 in the list of 189 countries) index by at least 50 notches in the next few years. Ajay Shriram, President of the Confederation of Indian Industries (CII), believes the labour reforms will lead to creation of job opportunities in the country.

Besides unveiling Shramev Jayate, the Modi government recently brought former Rajasthan Chief Secretary Rajiv Mehrishi into the Finance Ministry (as Economic Affairs Secretary in place of Arvind Mayaram). Since Mehrishi has been credited with scripting major labour reforms in Rajasthan, the central government’s move is being seen as an indicator of its positive intent.

THE Labour Ministry has drafted a separate law to regulate factories employing less than 40 employees. The Small Factories (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Services) Bill 2014 would allow such factories to register online, submit a single compliance report for all 44 labour laws and do away with many outdated provisions of labour welfare.

Yet, there are sceptics who are keeping their fingers crossed. “The announcements and proposals are no doubt good and will eradicate corruption. But I want to see when they will actually get implemented on the ground,” says Kosh Vasudeva, Welfare Officer in ITD Cementation, a multinational involved in construction of Metro projects in Delhi.

The industrialists look at curbs on inspector raj as directly proportionate to increasing ease of doing business in the country. They are doubtful about the success of Modi’s ‘Make in India’ pitch. “Inspector and business can never grow together. One can only grow at the expense of the other,” Saurabh Jain signs off.

(A few names have been changed to protect identity)