AFTER participating in the international conference on ‘Government Performance Management Systems (GPMS)’ in January 2017, I can say with confidence that Bhutan is the current leader in South Asia when it comes to implementation of government-wide GPMS. Bangladesh is close on the heels of Bhutan. Before I explain the reasons for reaching this conclusion, a word about the conference.

Organised by the BRAC Institute of Governance and Development (BIGD) in collaboration with the Cabinet Division of the Government of Bangladesh and the World Bank on January 22, 2017, the conference participants included government officials, members of civil society, leading academics, scholars, and policy makers from Asia and other countries.

| Table 1: Comparison of Evaluation Systems adopted by India, Bhutan and Bangladesh | ||

| 1 | Methodology used | All three countries use the same methodology that enables them to calculate a composite score at the end of the year |

| 2 | Structure of Performance Agreements | The Performance Agreements in all three countries have similar basic structure with minor variations. In India they are called Results-Framework Document (RFD). In Bhutan, Performance Agreements are signed between the Prime Minister and the Minister. In Bangladesh, a Performance Agreement is signed between the Cabinet Secretary and the concerned Secretary of the department. In India, RFDs are signed between the Minister and the concerned Secretary to Government of India. |

| 3 | Transparency | Performance Agreements documents are published on web portals in all three countries. |

| 4 | Trickling Down | The process of ‘trickling down’of accountability has taken place in all countries. From the federal level RFDs to state level RFDs in India. In Bhutan they have gone to the district and village levels. The same is true for Bangladesh |

| 5 | No Explicit Incentives | None of the countries have introduced performance-related financial incentives. |

| 6 | Results Published | Only Bhutan publishes the list of composite score for all Performance Agreements. India, the results at the federal level were conveyed to the Secretaries by the Cabinet Secretary and also included in the annual reports placed in the Parliament. |

| 7 | Budget Integration | In India and Bangladesh, the targets are decided after the budget has been firmed up. In Bhutan, they first agree on a Performance Agreement and then find resources to match the agreed departmental priorities. |

| 8 | HR Integration | The Civil Service Commission in Bhutan has integrated Performance Agreement with the HR system. |

| 9 | Political Commitment | Once again, Bhutan is ahead of the other two countries. The system is personally driven by the Prime Minister of Bhutan. In Bangladesh, the Prime Minister’s Office drives the system. In India, the political commitment was good enough to get started but could not be sustained. The story of the rise and fall of the GPMS in India will be told in a future article. |

The main presentations in the conference covered GPMS approaches in Malaysia, Bangladesh Bhutan and India – countries that are active in the region and have been part of a regional Community of Practice (CoP) hosted by BIGD, World Bank and the Government of Bangladesh. Set up in 2014, this CoP seeks to “promote peer learning and evaluation amongst practitioners of performance management in countries of South Asian Region (SAR) countries, as a practice to enhance the quality of policy dialogue, and subsequent delivery of public services. The main instrument for implementing GPMS is the preparation of Implementation Agreements (IAs) between a concerned ministry and the cabinet division.”

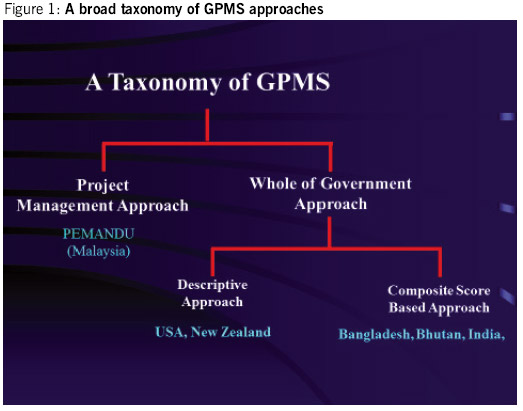

We can classify approaches to GPMS into two broad categories: (a) Project / Programme Management Type Approach to GPMS and (b) Whole-of-Government Approach to GPMS (see Figure 1). The Malaysian approach is all about effective design, management and implementation of select programmes. It focuses the entire attention of the government at the highest level on a few specific priority areas such as skill development, increasing rural connectivity, e-governance, etc. In Malaysia, these are called the National Key Result Areas (NKRAs) and are driven by Performance Management & Delivery Unit (PEMANDU), a unit set up in 2009 under the Malaysia Prime Minister’s Department to oversee the implementation, assess the progress, facilitate as well as support the delivery and drive the progress of the NKRAs.

WHILE PEMANDU type approaches have the great advantage of focus, they represent the classic water-bed phenomenon. When you press one part of the waterbed, the water goes to the other part. Similarly, when you focus on one aspect of the operations of government agencies, the inefficiency travels to other parts. Thus, government agencies may deliver the results that are under the scanner (what gets measured indeed gets done!) but it is not conducive to institutional development and sustainability – eventually the inefficiency in other parts of the agency and the government overwhelms the short-term gains.

The Whole-of-Government App-roaches, on the other hand, typically encompass all government departments and all aspects of a government department. However, such approaches, in turn, can be classified into two broad categories. As depicted in the figure above, one set of approaches are primarily descriptive and do not lend themselves to a more objective and meaningful evaluation. Performance Agreements under the 1993 Government Perfor-mance Results Act (GPRA) in the USA and Performance Agreements prepared under the Public Finance Act 1989 in New Zealand are examples of this approach.

The other set of Whole-of-Govern-ment Approaches are based on calculation of an overall ‘composite scores’ for Performance Agreements with government departments. This approach is represented by countries such as India, Bangladesh and Bhutan in South Asia. Similar approach has also been used in Kenya and South Korea. See John Kamensky’s blog in this space to know more about the underlying methodology of these approaches and the calculation of the composite score for Performance Agreements in India.

When you focus on one aspect of the operations of government agencies, the inefficiency travels to other parts. Thus, government agencies may deliver the results that are under the scanner but it is not conducive to institutional development and sustainability – eventually the inefficiency in other parts of the agency and the government overwhelms the short-term gains

This Whole-of-Government App-roach differs from the one used by the USA and New Zealand in three essential ways: First, all objectives, targets and Key Performance Indications (KPIs) are prioritised. Second, there is an ex-ante agreement on how deviation from targets will be judged. Third, at the end ‘principal’ is able to evaluate performance of the ‘agent’ on a scale of zero percent to hundred percent.

IN my opinion, approaches that do not arrive at a composite performance score are not sustainable in the long run. They involve a lot of subjectivity, are hard to defend and do not provide an accurate measure of performance. Therefore, what does not get measured well does not get done well!

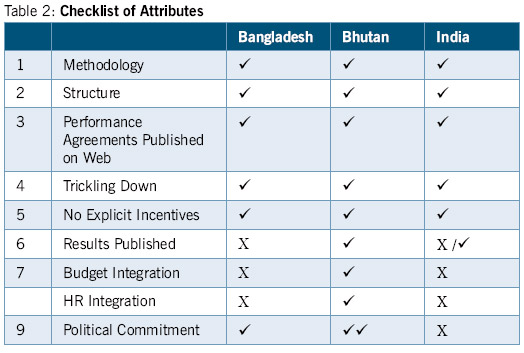

I will, therefore, focus on comparing similar approaches in the South Asia region. India was first to implement a whole-of-government performance monitoring and evaluation system in 2009. It was followed by Bhutan and Bangladesh in 2012 and 2014, respectively. The approach used by the three South Asian counties are compared on the basis of nine attributes as seen in Table 1. Table 1 is further summarised in Table 2. It is clear from this table that Bhutan is the leader in the South Asia.

Dr. Prajapati Trivedi is the former Secretary for Performance Management for the Government of India. He is currently the first Global Visiting Fellow at the IBM Center for The Business of Government, a visiting professor at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, Senior Fellow (Governance) and adjunct professor of Public Policy at the Indian School of Business. An earlier version of this