In March 2013, a concerned group of ex-bureaucrats, including some former cabinet secretaries, met then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh to advocate for urgent amendment to the incongruous provision (Section 13 1 d iii) in the Prevention of Corruption Act. The amendments providing some clarity to the corruption law were ultimately carried out five years later in August 2018. These amendments will hopefully encourage honest but cautious public servants to take decisions without fear of being prosecuted for making bona fide mistakes, which were earlier being treated as criminal acts under then prevalent law.

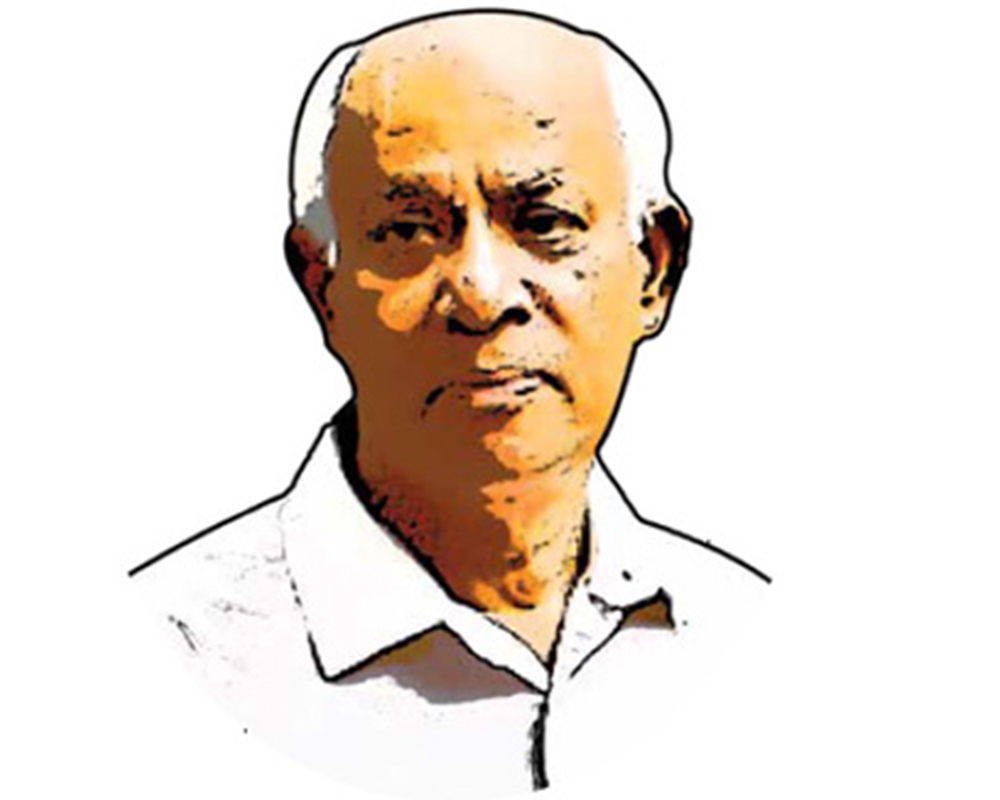

However, in an unprecedented third case relating to corruption within government, Harish Chandra Gupta, a universally acknowledged squeaky clean bureaucrat, has now been serially sentenced to three years’ imprisonment by a CBI court in a judgment which appears to be technically correct. It is fitting to recall that the bureaucrat, whose story will surely go into the folklore of independent India’s administrative history, had expressed his desire to be tried from a prison cell as he was unable to bear the heavy cost of litigation.

It is ironic to note that while hundreds of corruption cases routinely end in acquittals, every case involving this upright bureaucrat has been a successful case for CBI. Another significant point to be noted is that, if CBI version is believed, the ‘conspiracy’ to defraud the government was hatched by three IAS officers along with the beneficiary company without any common intention of either defrauding the government or making personal gain to themselves or any other questionable motive.

If CBI version is believed, the ‘conspiracy’ to defraud the government was hatched by three IAS officers along with the beneficiary company without any common intention of either defrauding the government or making personal gain to themselves or any other questionable motive

The now repealed clause of the CPC Act defined the offence as “while holding office as a public servant” obtaining “for any person any valuable thing or pecuniary advantage without any public interest”. This omnibus provision could have been used to penalise almost any decision of a bureaucrat since almost every decision would lead to pecuniary advantage for some person. Even routine approvals for a ration card or caste certificate would qualify for such an offence. Almost every retired civil servant (including me) could have been prosecuted under the now repealed provision by CBI without the need of prior government sanction. The only distinguishing ingredient for establishing criminal misconduct was ‘without any public interest’. In the case of Harish Gupta, neither CBI nor the court has been able to establish any personal gain or mala fide. One fails to understand why would a senior IAS officer ‘conspire’ to do something unlawful for no obvious rhyme and reason.

Another significant actuality of the cases against the three bureaucrats is that the final approving authority of the licences was not indicted by CBI or the court even for negligence or carelessness. We are made to believe that he was “misled” by not being told that certain guidelines had not been followed!

Anyone who has worked in Government of India knows the strength of Prime Minister’s Office, which has increased with each passing year. With some of the sharpest civil servants and other specialists working for the Prime Minister, it is virtually impossible to ‘mislead’ decision making there. Every matter referred to the PMO is scrutinised with care from every possible angle before being put up to the Prime Minister for approval. And to ‘mislead’ the Prime Minister again and again in an identical manner by the same ministry appears to be too weird for my understanding.

Surely Dr Manmohan Singh would be aware of the fact that his erstwhile Coal Secretary is undergoing repeated trials in the cases in which licences were approved by him. Surprisingly, he has not uttered a word till now sympathising with the undeserved fate of the civil servant, though I do not know whether he has averred to the matter in his recently launched five-volume biography.

My intention is not to locate flaws in Court’s reasoning while coming to the conclusion about Harish Gupta’s culpability. These have been articulated by several commentators and will be duly tested in the higher courts in appeal. My intention is also not to defend him because of my personal knowledge of his upright conduct for decades. Suffice to say, no one who has worked with him anytime during his entire career can believe that Harish Gupta can even think of doing something questionable, leave alone being corrupt.

But it is the after effects of the unfolding drama that cause concern to those opting to work for the government as well as for the quality of governance at various levels. For instance, a genuine dilemma for those involved in decision making would be whether to stick out their neck for innovative and progressive ideas. A former civil servant laments, “Who knows which bureaucrat of today will be making the rounds inside Tihar Jail a decade hence! It will not be surprising if the bureaucracy adopts the motto “each man to himself and the devil take the hindmost”. He goes on, “Little wonder then that, today, the offspring of politicians, film actors and businessmen follow their parents’ professions, while the well-educated, talented daughters and sons of bureaucrats become lawyers, IT professionals and academics. If the bureaucracy loses valuable human capital, we have only our systems to blame for it”.

The rejection of the plea of the IAS officers that they depend on the subordinate officials for the correctness of facts on the files may also have some serious impact on decision making. The secretary has been held responsible for discrepancies in the applications and as the chairman of the screening committee fully accountable for every lapse. A former cabinet secretary says that ‘I have not seen a secretary examine primary documents, particularly when the administrative ministry and state government were sent the papers for comments’. But in future, a secretary would satisfy himself/herself of the veracity of every fact on the file before submitting it to higher authorities. In essence, the degree of distrust within administration would increase.

Finally, I am of the view that law might have been applied rightly in letter in Harish Gupta’s case but justice has not been dispensed. In many respects, his trial is reminiscent of Franz Kafka’s celebrated novel. Even though it is difficult to foresee the precise upshot of this case on the morale and functioning of bureaucracy, one can surmise that it would tend to upset the intrinsic belief in one’s ethical conduct as well as disrupt the trust in politician-bureaucrat relationship.

Endpoint: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us………” so wrote Charles Dickens of the nineteenth century Europe. Watching public governance today, it could equally have been said about our times in this country.

The writer is former Cabinet Secretary

Prabhat Kumar is an Indian Administrative Service officer of the 1963 batch, he served as the Cabinet Secretary of Government of India between 1998 and 2000. Upon creation of the State of Jharkhand in November 2000, he served as the first Governor.