A new chapter was recently added to the old debate on the relationship between the political executive and the senior bureaucracy when the Chief Secretary of National Territory of Delhi accused a couple of legislators of the ruling party of assaulting him in the presence of the Chief Minister and the Deputy Chief Minister. Notwithstanding the special status of Delhi as a Union Territory State with confusion about the supremacy of the elected government, it was a moment of reckoning for civil servants. And having spent a large part of my life in government, it set me thinking on the subject of coexistence of politicians and civil servants in a democratic set up.

It has been my recurrent discontent that the civil servants do not pay much attention to reflecting on the essence of public service adequately, and that they have failed to create sufficient energy in their transactions with the citizen. They do not see the need to force changes in the existing mode of administration. They underestimate their designated role in the system and are content to live in their comfort zones. They do not realise that their action reinforces the status quo.

It is a truism that the craft of state building requires both a political executive to envision the wishes of the people and a permanent civil service to help translate them into reality. It is also true that the subject of politician-bureaucrat relationship has not attracted much attention from the political thinkers in our country. I for one consider this relationship as critical in a growing democracy like India. Since the politician does not show much interest in resolving the problem, the civil servant will have to try to steer the relationship in the best interest of the State while keeping the institutional integrity intact.

Over the years, a number of incidents relating to the unsettled relations between the political bosses and bureaucrats have been making news. Top civil servants being shown the door unceremoniously and public scolding of district officials by the ministers are common occurrences in some states. There have been several cases of constructive cooperation between the two in acts of organised corruption. But an allegation of physical assault on the chief of the civil service in a State was something unusual. I refrain from expressing my views on the incident because the facts are unclear and vehemently disputed.

This comprises one of the three cardinal mistakes the senior civil servants of India have been making for decades. The other two are acting alone and not having a cogent vision of the Indian civil service. But they are a subject for another day.

Political executive in a parliamentary democracy are, by design, the instruments of the elected government to realise the aspirations of the electorate. They hold their positions because they have won the verdict of the people on public policy. They are expected to be willing and able to work to see that the wishes of the people are implemented at the agency level in accordance with law and regulation. They perform a critical function: working to translate the wishes of the people into policy initiatives.

Career civil servants perform a very different role. They implement policy, besides helping to make it. They provide continuity and specialised expertise based on institutional knowledge and experience. Traditionally, most of them spend their entire working careers in government, although in our country nowadays it seems to be changing.

My first hypothesis is that these roles are separate, and it’s important to do all we can to keep them separate. And this must be realised by both the actors.

The model of Weberian bureaucracy, which has largely been adopted by us, insists on a permanent civil service with standards of efficiency, integrity, objectivity, political indifference and domain knowledge. It has also the capability to transfer its expertise and loyalty from one elected government to another.

The last feature of Weberian bureaucracy poses problems. While it does not matter much in an established democracy where mainstream political parties have settled agendas, the Indian scene with its cacophony of ideologies requires a chameleon like civil service. I have been personally a witness and an accomplice in the game of shifting loyalties. In the seventies I was instrumental, in a small way, of justifying the imposition of Emergency by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, and later under Janata government, of taking action in cases of Emergency excesses. This type of situation is experienced by hundreds of civil servants today. And the new phenomenon of coalition governments has made matters even more complicated.

I have seen the last days of a healthy synergy between political masters and civil servants in the initial years of Indian democracy. It was a period of uniformity within the executive, when both the limbs worked with a shared purpose of building the nation. Several instances come to my mind when career bureaucrats advised the ministers against their chosen course of action and their advice was heeded to. There are instances of the two sitting together and deciding on schemes and programmes for the people in the field. An elegant example of constructive cooperation between the two was the great green revolution of the sixties. There was hardly any complaint of political favouritism or official corruption. District officers were not shifted at the behest of local politicians before or after elections. Political transfer of secretariat officers was unheard of. Almost invariably an honest and upright district magistrate was supported by the state government.

The civil servant respected the political leader, whether in or out of power, for his leadership qualities and his influence on the masses cultivated and nurtured during the freedom struggle. The politician was aware of the needs of the people at the micro level, could identify with them and feel their pulse. He was pragmatic and purposeful.

The politician respected the civil servant for his impartiality, adherence to lawful authority, uprightness, integrity and knowledge of the subject. He could rely on the bureaucrat working under him for right advice and faithful implementation.

When the two started working together, it was expected that the respective roles would be defined and further refined. Intensifying democratic processes should have been accompanied by role definition, which unfortunately did not happen. Merely saying that ‘the politicians take decisions and the babus advise and implement’ was not enough. It left room for arbitrariness and sloth.

The vaguely defined rule of democratic supremacy of the political executive in decision-making unfortunately descended and permeated into the lower echelons of government, where the role of the civil servants was crucial to the implementation of the decisions taken upstairs.

Thus the synergy between the political executive and the permanent civil service that existed in the fifties and the sixties has been largely eroded over the years. It has had a very deleterious effect on the quality of governance in the states and also in the central government. It has given way to mutual distrust and at times, even to open conflict.

Earlier, difference of views between the political master and senior civil servants were normal and frequent. When Sardar Patel was asked whether he would remove his secretary if he expressed conflicting views, Sardar replied, ‘No, but if he always agreed with me I will definitely remove him’.

The internal synergy came under strain for several reasons. Ministers did not like secretaries voicing their disagreement either in discussions or in the files. There were instances where ministers prevailed on Cabinet Committee on Appointments to change secretaries of their ministries. Senior officers stopped taking proactive actions in policy making and deciding important cases. They are doubtful whether their actions would be supported by ministers in enquiries instituted in future.

It did not happen suddenly. It was like the boiling frog syndrome. It was the gradual introduction of temptation in governance. It was an extraneous impulse mainly from emerging trade and industry. The take off time of Indian economy heralded an era of greed. Soon we were in a no-holds barred, all stops pulled game of profits.

Consequently the top of the government started falling and then the bottom gave way too. Trust turned into distrust, mutual respect into uneasy coexistence with perilous consequences for the working of a democratic government. The politicians and the bureaucrats together brought down the monolithic structure like a castle of cards.

My second hypothesis is: An effective and honest civil service cannot coexist with a self seeking political system or a flawed business environment. As the former Speaker Somnath Chatterjee said in the National Summit on Restoration of National Values, “We cannot get good governance from bad politics.” And it is equally true for bureaucracy.

The reason is simple. Where there exists a synergy between the two arms of the executive, policy making is a smooth process and there is rarely resentment among the civil servants regarding discriminatory treatment. You do not hear of preferential postings on the basis of favouritism. There is no demand for a civil service board to decide on postings and transfers. The relationship is based on trust as it should be in a responsible democratic system.

And that brings me to my third hypothesis: That a responsible democratic system has to be based on the principles of ethics of governance.

I was introduced to the term ‘ethics of public governance’ when I was in the government and learned about an international colloquium on the subject in Brazil towards the end of the century. Since then it has been studied by a number of thinkers in the World Bank and UNDP. The literature on the subject is growing.

The Centre for Governance, with which I am associated, has been running programmes for the last more than a decade on ‘ethics of governance’ for senior civil servants with promising results. I think there is a need to expose the members of the political executive to similar programmes. One of the State governments had shown interest of training the members of State Assembly in ethics of governance. It is our belief that such orientation programmes would help in recreating a semblance of the internal consistency in the government.

Endpoint: We must remember that there is nothing trickier to embark on or more uncertain than rearranging the equation between the elected and the selected.

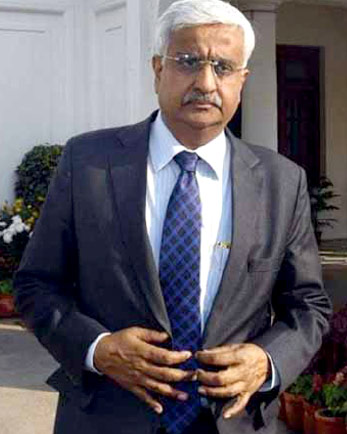

The writer is former Cabinet Secretary

Prabhat Kumar is an Indian Administrative Service officer of the 1963 batch, he served as the Cabinet Secretary of Government of India between 1998 and 2000. Upon creation of the State of Jharkhand in November 2000, he served as the first Governor.