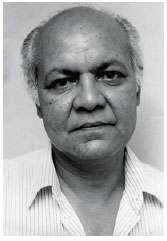

Janardan Thakur started his career in journalism with the nationalist Patna daily, The Searchlight, in December 1959. In his long and distinguished career spanning the reign of each Prime Minister since Independence, Thakur reported from the thick of some of the most momentous contemporary events at home and afar—JP’s ‘total revolution’, the Emergency, the bristling emergence of Sanjay Gandhi, the fall and rise of Indira Gandhi and then the rise and fall of Rajiv, the Kremlin of Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and Khomeini’s revolution in Iran, Ronald Reagan’s re-election in an America swinging Right, VP Singh’s ascent as a messiah with tainted magic and the rasping run to power of the BJP. Thakur’s journalism, from the very start, broke traditional moulds of reportage and writing, going beyond the story that meets the eye and into processes and personalities that made them happen. His stories on the Bihar famine of the mid-1960s and the manmade floods that ravaged the State were a sensation. He was perhaps alone in predicting defeat for Indira Gandhi in 1977 and again singular in exposing the corroded innards of the Janata Government that followed. A Jefferson Fellow at the East-West Center, Hawaii, in 1971, Thakur moved to New Delhi as a Special Correspondent for the Ananda Bazar Patrika group of publications in 1976. He went freelance in 1980 and turned syndicated columnist. In 1989-91, he was Editor of the fortnightly Onlooker, and The Free Press Journal. Thakur authored All The Prime Minister’s Men, probably the most successful of the crop of books that followed the Emergency. His All the Janata Men, the story of the men who destroyed the first non-Congress government in New Delhi, was equally successful.

Janardan Thakur started his career in journalism with the nationalist Patna daily, The Searchlight, in December 1959. In his long and distinguished career spanning the reign of each Prime Minister since Independence, Thakur reported from the thick of some of the most momentous contemporary events at home and afar—JP’s ‘total revolution’, the Emergency, the bristling emergence of Sanjay Gandhi, the fall and rise of Indira Gandhi and then the rise and fall of Rajiv, the Kremlin of Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and Khomeini’s revolution in Iran, Ronald Reagan’s re-election in an America swinging Right, VP Singh’s ascent as a messiah with tainted magic and the rasping run to power of the BJP. Thakur’s journalism, from the very start, broke traditional moulds of reportage and writing, going beyond the story that meets the eye and into processes and personalities that made them happen. His stories on the Bihar famine of the mid-1960s and the manmade floods that ravaged the State were a sensation. He was perhaps alone in predicting defeat for Indira Gandhi in 1977 and again singular in exposing the corroded innards of the Janata Government that followed. A Jefferson Fellow at the East-West Center, Hawaii, in 1971, Thakur moved to New Delhi as a Special Correspondent for the Ananda Bazar Patrika group of publications in 1976. He went freelance in 1980 and turned syndicated columnist. In 1989-91, he was Editor of the fortnightly Onlooker, and The Free Press Journal. Thakur authored All The Prime Minister’s Men, probably the most successful of the crop of books that followed the Emergency. His All the Janata Men, the story of the men who destroyed the first non-Congress government in New Delhi, was equally successful.He passed away on July 12, 1999.

Wednesday, August 20, 1980. It was the birthday of Rajiv Gandhi. He was thirty-six, and on the threshold of entering the ‘family business’. You could feel it in the air. It was so unlike other birthdays. Earlier, it used to be more of a family affair, with some close friends of the family joining in to say ‘many happy returns of the day’. Now there was a rush of politicians and social climbers, all vying with one another to present their bouquets to the young man they had hardly paid any attention to in the years gone by, except as ‘the other son of Indiraji.’ Even some of the MPs of the Sanjay brigade were around to propitiate the rising Son of India.

Mrs Gandhi wore a big smile, her large round reading glasses which she had newly acquired giving her a touch of modernity. What lay behind the smile and the glasses was difficult to tell, for she could be so good at keeping her real feelings to herself. Sad and yet happy, or happy and yet sad. But this was quite an occasion, especially with the new plans being set for Rajiv’s formal entry into politics. More reason why everyone noticed one conspicuous absence: Maneka Gandhi. Not that she was in deep mourning like a traditional Indian widow. The story was told about how she had behaved on the day Sanjay Gandhi was cremated. She had come out dressed in salwar kameez. Mrs Gandhi had raised her eyebrows with disapproval and told one of the ladies to tell Maneka that a plain sari would be more suitable for the occasion. Maneka had reacted sharply: “Go tell her I don’t have a sari.” The lady came back and told Mrs Gandhi. “Is that so?” she had said, but this was no occasion for creating an issue, so she told the lady to ask Maneka to go and select a suitable sari from her wardrobe. Maneka again reacted sharply, “Go and tell her I don’t know how to wear a sari.” She wanted to make it clear that she was not a traditional daughter-in-law who could be pushed around by her Saasji. She liked being in salwar kameez and that was what she would wear whether Mrs Gandhi approved of it or not.

Mrs Gandhi had ordered a surveillance of Maneka and her mother, Amteshwar Anand. Indira had a strong dislike for Mrs Anand even when Sanjay Gandhi was alive. Insiders talked about an interesting incident which had taken place just before one of the Assembly elections. The AICC had chosen about half a dozen printing presses in Delhi and other cities to get the campaign posters and other publicity material printed. It was a big job, with big money in it. With Maneka Gandhi sitting pretty in the Prime Minister’s house, it was not difficult for her mother to find out about the decision to give the orders to various printing presses. Being a printer herself, Mrs Anand got in touch with executives in the party office and steamrolled them into cancelling the orders to other printers and giving all the work to her. She wanted the orders the same day, which was done. Mrs Gandhi came to know of it. She was furious. One of her secretaries called Mrs Anand. “The Prime Minister wants to see you immediately in the South Block.” The lady rushed to the PMO. Very coolly, Mrs Gandhi asked her about the printing job she was supposed to be doing for the poll campaign. Yes, said Mrs Anand, she had already got the orders. She would like to see the letter, Mrs Gandhi said. Mrs Anand said she would bring it some time. No, said the Prime Minister. She would like to see it right away. A little rattled by Mrs Gandhi’s tone, Mrs Anand had rushed to her Maharani Bagh residence to get the letter. Mrs Gandhi read the letter, tore it into pieces and threw it into her waste paper basket. Mrs Anand went pale. On top of it she got a lecture: Don’t try to muck up the Gandhi family’s reputation.

Act I of the murky Saas-Bahu drama, however, had gone in favour of Maneka Gandhi. She had emerged from it as a long-suffering young widow, abused and thrown on the street with a two-year-old son for no greater sin than raising the banner of her late husband, who had been the ‘apple of Mrs Gandhi’s eye’ and the main architect of her return to power.

Rajiv Gandhi was more important to Mrs Gandhi now. She had even summoned a team of Namboodiri tantriks from Kerala to do a yajna and change his mind. There were signs that he was weakening in his resolve not to join politics. He had made an appearance at the AICC(I) meeting in New Delhi, then joined in taking a pledge with the Youth Congress(I) workers. He had even started meeting party general secretaries for discussing the plans for a Kisan Rally. It was the only-helping-Mama phase. In an interview to Khaleej Times, Dubai, Indira Gandhi said, “At present he (Rajiv) has no specific role in my official life…he helps in running my household, in my meetings with unofficial people, people who come with ideas, and younger people…” Five days after this was published (May 3, 1981), the Congress (I) parliamentary board named Rajiv Gandhi as the party’s candidate for the Amethi seat, which had fallen vacant because of Sanjay Gandhi’s death. The very day he left Indian Airlines, he was made a member of the Congress, and within a month he took his oath as the MP from Amethi. Saying no, no, no, like the fair victim of Byron’s Don Juan, Rajiv Gandhi had consented.

Image-makers and whiz-kids gathered fast around him. Old chums from Doon School, most of whom had come through the management cadres of the private sector. An executive in Reckitt and Coleman which sold Dettol and Cherry Blossom, another a senior executive in Hindustan Thompson. Another circle had men like Vijay Dhar, who owned a chain of hotels in Delhi and Srinagar, and Makhanlal Fotedar, a former minister in Jammu and Kashmir and election agent of Mrs Gandhi in Rae Bareli. Heading them all was the heavyweight Arun Nehru, who had left the paint company Jenson & Nicholson, to fill the vacancy left by Mrs G in Rae Bareli. A cousin of Rajiv at third remove, Nehru was assigned the task of ‘shielding and protecting’ Rajiv Gandhi. Nehru did not take much time earning for himself the image of a bully, the operating political arm of Mr Clean.

A vital question was of Image. What kind of image should Rajiv project? Should he wear a Gandhi cap for his election campaign? Yes, said the image-makers, he should project the Nehru image. He should continue the tradition and adapt it to the ethos of the times. He should march the people of India to the 21st” century. Rajiv’s image had to be different from Sanjay’s, close to a ‘Jawaharlal of a new era’.

The pretence of shying away from publicity went overboard. The sprawling palace grounds at Bangalore saw the political launching of Mr Clean. Gathered there to pay court were at least four chief ministers, 18 union ministers, 40 ministers from various states, all the AICC general secretaries, about 200 MPs, over 800 MLAs and 40,000 delegates. All taken to Bangalore in special trains. The estimate of costs: anywhere between two and ten crore rupees.

After Rajiv was elected MP, there began orchestrated demands that he be given some important responsibility in the party. Again, 300 AICC members wanted him to be made at least the party general secretary. Only months earlier, Rajiv Gandhi had gone on record to say it would be a mistake on his part to contest any byelection, that he was opposed to being pushed into a senior position in the Congress and would rather start from scratch and rise gradually.

The build-up continued. Pollsters close to the establishment carried out an opinion poll. To justify their exercise, they said: “His (Rajiv’s) future has obviously great relevance in respect of the political scene after Indira Gandhi retires from the political leadership.”

The Indian Institute of Public Opinion juxtaposed Rajiv Gandhi against Atal Behari Vajpayee, who had emerged with the highest score in a Gallup poll of the opposition leaders. Result: Rajiv emerged with a higher score than Vajpayee, 67 against 58. “One might be tempted to argue,” said the pollsters, “that his acceptance in the political milieu has been remarkably rapid even though this operates now only over less than half the electorate (a high percentage of 57 had expressed no opinion). The question may be asked if he is ranked now on his own right. He heads no party and perhaps he is currently judged not on his own performance or that of his party but the faith reflected in the charisma of his mother…his personal ranking cannot be assumed to be of his making.” Rather carefully worded, but the drift was clear.

The Congress had been reduced to a private limited company of Indira Gandhi, so there was no hurdle for Rajiv Gandhi anywhere. Anyone who had the potential of posing a threat at any point of time in the future was weeded out or cut to size. Only two faces could grace the pages of the fortnightly party bulletin — the mother and the son.

Pradesh Congress Committees started coming up with the demand that he be elected the president of the party, of course with the inevitable rider, “if lndiraji chooses to step down from the post.” Puppets on the string. The ‘draft Rajiv’ move had the highest sanction, and even without office he had become ‘the second most powerful person in the country’. Whenever chief ministers went to see Mrs G., she invariably told them, Rajiv se bhi mil lijiye. Dossiers on all Congress politicians worth the name were already being fed into RG’s computers.

The Deccan campaign was to be the high point in the projection of Rajiv Gandhi. It was taken for granted that the Telugu film god notwithstanding they would sweep “Amma’s old pocket borough”, Andhra Pradesh. The glory of it was to go to Rajiv, and to him alone. He had done a lot of home work for the campaign, making the fullest use of computers. Every little data had been fed into them, the antecedents and backgrounds of all the possible party candidates had been thoroughly analysed by the machines— castes, sub-castes, affiliations, strengths, weaknesses. All outmoded procedures of candidate selection were dumped as utter bakwas…The best marketing and ad brains had worked overtime to create slick slogans and campaign.

Rajiv Gandhi returned from the ‘Deccan campaign’ routed. Critical, though muted, voices began to be heard even from within the Congress: ‘A good man, but ineffective…no dynamism at all… no patch on Sanjay…’ Maneka was openly describing him as ‘that dumb man’, ‘an innocent abroad in politics’. Something had to be done to correct the image. Fast. And so Rajiv Gandhi suddenly appeared in public as a stern man giving a dressing down to the police commissioner of Delhi. Were even his rebukes to Anjiah at the Hyderabad airport a well-calculated step to give him a tough, clean image? Rajiv had been taking long lessons on how to walk and smile and wave and throw garlands to the children ‘like Chacha Nehru’. Even when he visited Amitabh Bachchan at the Breach Candy hospital where the superstar was fighting for life, the training seemed to get the better of Rajiv Gandhi. He smiled and waved to the sombre crowd thronging the hospital.

But these are only minor hazards of political acting. His promoters were sure he would come out with flying colours. What was needed, they thought, was to bring him into the mainstream fast. He was pushed further into the tracks of Sanjay Gandhi. Mrs Gandhi finally gave in to ‘public pressure’ and made him general secretary of the Congress. The selling of Rajiv Gandhi had entered a decisive phase. Even Mrs. G had come a long way in relation to her son—from ‘he is not entering politics’ to the stage of ‘I am not grooming him for the prime ministership.’ The pretence of ‘only helping Mamma’ had gone overboard. The Malayalam Manorama bureau chief in Delhi, TVR Shenoy, told the story of how the PM had helped in the image-building of her son. The editor-in-chief of the Readers’ Digest, Edward Thompson, called on Mrs. G and complimented her for the excellent arrangement during the Asiad Games. He said the big success was because of her. “Not because of me,” said Mrs. G, “not because of me, it was all because of my son, Rajiv.”

Every success was now to be attributed to RG. No post, no office was to be given to anybody without his being in the picture. When VC Shukla was made the Chairman of the Congress manifesto drafting committee, the media was told that they must not forget to say that the appointment was conveyed to Shukla by RG. Anybody who got anything had to feel obliged to him.

If until some time ago, the image builders were anxious to project him as a great manager, whether of the Asiad or the Kisan Rally or the NAM summit, the emphasis now was on his image as a politician out to clean the mess in the country. The removal of Jagannath Mishra, a Bihar politician with a dubious image, was meant for the greater glory of RG, to show that here was a man who meant business, who wasn’t just a namby-pamby Mr Clean. If in the process the image of the so-called Working President of the Congress, Pandit Kamalapati Tripathi, got a further knock it was all for the better. Just a few days before Jagannath Mishra was brought down from the Chief Minister’s seat, Kamalapati had pooh-poohed the possibility of a change in Bihar and said he had given his blessings to Jagannath. The decision to remove Mishra was meant to show that Tripathi was of no consequence to the party. Most of the party functionaries were now concentrating on singing hallelujahs to the ‘heir apparent’. CM Stephen kept repeating the same theme, with minor variations: “If he is a good husband, a good pilot, a good son, he can also be a very good leader.”

Not to be forgotten was his image abroad. No opportunity was to be missed, whether it was the wedding of Prince Charles or the Festival of India or the PM’s visit to the US. The team was organised in such a way that RG automatically became the No.2. Usually no ministers were included on the trips. The Russian visit was specially packaged to give the ‘product’ a big boost. The Kremlin bosses must have seen it as a remarkable opportunity to win the mother’s heart, and they did just that by virtually anointing Rajiv as Mrs G’s heir.

Four years back in power, Mrs. Gandhi was into the same old tricks again. She always viewed the Opposition as an unnecessary evil. “Her demonology includes all politicians who are not actively promoting the continued rule of the Congress, and the Gandhi family which in her view personified it.” The Opposition was now in such a pathetic state that she simply did not have to bother about them. The left alliance and the right alliance were at daggers drawn. Practically every leader of the Janata Party, now gentlemen of the Opposition once again, had his own party. There was the Janata Party still, whose split had led to the founding of the Bharatiya Janata Party; the Democratic Socialist Party, invented by the man of many tricks, Bahuguna, after he left, successively, most of the Opposition parties. Party alignments had become meaningless. She faced no threat, or so it seemed. “Like a warrior goddess Kali, she set out to smite all centres of opposition power, starting in the tiny ex-kingdom of Sikkim, moving on to terror-ridden Punjab, and then to the opposition-ruled state of Kashmir.”

In the autumn of 1983, one of the official propagandists of the Prime Minister was hunting discreetly for some senior journalist who could do an “investigative” book on the “treacheries” of the J&K Chief Minister, Dr. Farooq Abdullah. When it was suggested to the bureaucrat that he could find any number of bandwagon journalists to do the hatchet-job, especially with the kind of attractive “official assistance” that he was offering for the assignment, the gentleman said, “But that’s not the sort of journalist we want. We are looking for someone who is not known to be a pro-establishment man, if you know what I mean…Some journalist with credibility.”

This was obviously a part of the plot then being hatched to pull down the Farooq government. Even before Farooq won a landslide victory in the Assembly elections, iron had entered the soul of Mrs. Gandhi. All her men were getting ready to strike. “In any case, we will not accept the defeat,” threatened Arun Nehru, and the then Congress General Secretary, Rajiv Gandhi, was himself saying, Agar haath chalana pada to chalaya jayega — If we have to strike, we will strike. There was hardly a public meeting or a press conference where they did not single out Farooq Abdullah for a frontal attack. The tirade reached a high pitch at the Congress session in Calcutta where Rajiv Gandhi virtually declared Farooq a traitor. Among the charges he levelled against him was that the extremists in Punjab were being trained in Jammu and Kashmir. But much to their chagrin, the then Governor of J&K, BK Nehru, a cousin of Jawaharlal, was ‘not playing ball.’ He was refusing to recommend the dismissal of the Farooq government. Delhi was looking around for the right man to do the job. They were soon to find one. Who but Jagmohan? The toppling game was begun in right earnest, and in July 1984, a government of defectors from the National Conference, led by Farooq’s brother-in-law, Gul Mohammed Shah, was put in the saddle. The denigration of Farooq continued with added vigour, culminating in the publication of a 113-page ‘White Paper’ against the Abdullah Government.

Mrs Gandhi was jubilant about one aspect of the J&K elections: she had demolished the citadel of the BJP in Jammu. This had driven her to the conclusion that she could win elections by relying essentially on the Hindus. After the results of the Delhi elections, she had told her confidants: “If Muslims do not want to vote for me, what more can I do for them?” After this, she was no longer subtle in appeasing the Hindus. She did not decline any invitation to a Hindu religious function. She went for the 90th birthday celebration of Jagadguru Chandra Shekhara Saraswati Sankaracharya Swami of Kanchi. Mrs. Gandhi’s Hindu bias and obscurantism, wrote Kewal Varma of The Telegraph, had begun to strike a sympathetic chord in the mind of the RSS leadership. Bhausaheb Deoras, younger brother of the RSS chief Balasaheb Deoras in an in-house discussion once said, “If the country’s unity and values are in danger, obviously we will go along with Mrs. Gandhi.”

The famous lady was now more and more like a tired and jaded tragedienne who has long run out of script and would not give up her desperate effort to create an effect. One after another she pulled out all the old and oft-repeated tricks of her repertoire, mouthing bits and pieces from various other roles she had played before, picking up, when stuck from the medley of prompting by worn-out advisers in the wings. Quite like a crazy act of a long and tiresome burlesque.

Where, I often wondered, was the Indira who had risen, Phoenix-like from the ashes? Where was the great comeback artiste? Where was the leader I had followed on those first two forays out of Delhi after that stunning defeat?

Her first journey had been to Paunar to Vinoba Bhave’s Ashram. The Bhoodan leader was observing karma mukti and would talk about nothing except ‘health and spirituality’. After two days at the Ashram, Indira Gandhi expressed her great faith in Vedanta. “I try to live according to it,” she told pressmen who had rushed from Nagpur, and were eager to know the purpose of her three-day pilgrimage to her “Sarkari Sadhu”. She had ‘wide-ranging talks with Vinoba” but ‘no politics’. The newsmen, people of little faith that they are, had kept speculating about the six rounds of talks she had. One little phrase that had slipped out of the closed room was Vinoba’s advice to her: Chalte Raho. One could interpret that in many ways, and indeed there were as many interpretations as people. One Ashramite had come out with the explanation that it was only his advice for “keeping fit — the more you work the fitter you are. Chalte Raho.” But it had been similar to the slogans raised all the way from Nagpur to Paunar: Indira Gandhi aage badho, hum tumhare saath hain — Indira Gandhi, move ahead, we are with you.

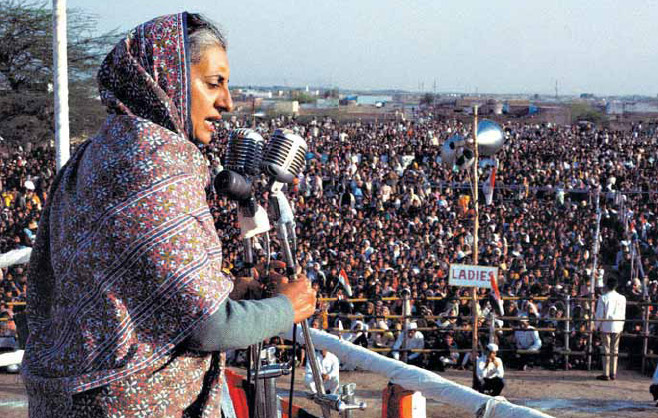

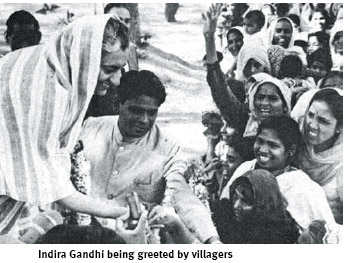

It was not for nothing that she had taken her first trip out of Delhi. She was out to get a feel of the people’s mood, some months after her fall. Would they respond to her, or did they still hate her? Whatever she may have talked with Vinoba, there was little doubt that the visit was political. Her little roadside speeches showed she was once again trying to project herself as the ‘only real friend of the poor and the downtrodden…the new leaders of the country were incapable of doing anything for them…’

When she set out from Palam airport early in the morning of July 24, 1977, there were dark pouches under her eyes and she had looked tense, a little apprehensive. It was the first time in many years that she was moving out as a commoner, and even though Nagpur was in a Congress-ruled state, who could tell how the people would behave? But as the day passed and she saw the little knots of welcoming people, her eyes brightened and she found something of her old touch. When some people asked her when she would come out, she said: “Haven’t I already come out?” Emboldened by all the adulation and feet-touching of the three days, she said on her way back that there was really no question of her returning to politics, as she had ‘never left politics.’

The only question was about the new stance she should take. Vinoba was said to have told her that for some time at least it would be better for her not to take a strident political posture. That could aggravate the opposition inside the Congress and also sharpen the attacks on her by the Janata Party leaders. Why not start with programmes like Harijan welfare and rural uplift? Why not undertake padayatras? That would give her a new acceptability among the people.

Indira Gandhi had lost no time in drawing up a plan to start from her erstwhile constituency, Rae Bareli, and sent off her aide, Yashpal Kapoor, on a reconnoitring mission. After Paunar, it was Belchi where 11 persons, most of them Harijans, had been burnt alive. Once again she had taken the front window seat in the plane to Patna. She sat back, looking out of the window most of the time. The pouches under her eyes looked a little baggier, the strand of grey in her hair a little more ruffled. She would take none of the refreshments offered by the air hostesses. Nothing. It was a long motorcade that had followed Mrs Gandhi’s car from Patna. At places there were welcome arches and at one place a band played: Jo shaheed huey hain unki zara yaad karo kurbani…”

At one point, some local Congressmen told Mrs G she would have to cancel her trip to Belchi. The route was too bad, and it had rained. “I will reach there,” she insisted and the motorcade moved on. Some miles from Belchi the motorable road petered out into a slushy path. Her car got stuck. A jeep was brought, and even the jeep got stuck. “We can’t go any farther, there is too much mud and water ahead,” one of the netas said. She got off the jeep and started walking. “I will go to Belchi even if I have to wade through mud and water.” Then they brought an elephant and she climbed up, saying, “This is not the first time I have ridden an elephant’s back.” Everybody along the way cheered, and even cameramen who had come all the way from Delhi shouted, Long live Indira Gandhi! A scrawny old woman in her eighties, standing at the door of her house, raised her skeletal hand and pointed her finger toward the elephant and said to the little girl beside her: Dekho, desh ki rani jaa rahi hai — Look, there goes the country’s queen. She didn’t know that another man was on the throne now, or if she knew she didn’t care.

The elephant ride to Belchi gave Indira Gandhi a big leap over all her political rivals. Belchi had also given Indira Gandhi a pretext to call on the man who had brought her down: Jayaprakash Narayan. She had gone to his Patna residence next morning, looking cheerful and bright. The fifty-minute tete-a-tete with JP made her look even brighter. Perhaps because of his blessing to her: “Have a bright future — brighter than the bright past you have had.” Some said she had won him over, some said it was a tongue-in-cheek statement, and still others said there was ‘no need to attach any importance to the statement.’ In any case, after that meeting, JP never said a word against Indira Gandhi again.

The future did not look bright at all. Thoughtless use of power had made Indira Gandhi commit strange and foolish acts. In Sikkim, she struck down a majority government, and emboldened by the ease with which she had disposed of the governments of Akali Dal in Punjab and of the National Conference in Kashmir, she was now ramming the fort of the Telugu Desam chief minister, NT Rama Rao. The dethroning of Rao, who had become famous playing gods in Telugu films, sparked an uproar in Andhra, Delhi and beyond.

Punjab had turned into a nightmare. It was a nightmare of her own making. Mrs Indira Gandhi had connived with Giani Zail Singh and her son, Sanjay Gandhi, to build up Sant Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale as a counterfoil to the Akalis, and had ended up creating a Frankenstein monster for herself. Later, even as Bhindranwale and his fierce gang of militants were turning the Golden Temple into an armed camp, the new general secretary of the Congress, Rajiv Gandhi, was insisting that Jarnail Singh was ‘just a spiritual leader’ of Punjab. Political naivety could hardly get worse. Operation Bluestar was the end-result of Indira Gandhi’s paranoia and mindless policies. It was the fruit of the poison tree she had planted.

Sometime after midnight (New York time) on October 31, 1984, I had been woken up in my friend’s apartment on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan. On the telephone was the editor of The Overseas Times, a newspaper for Asians brought out from Jersey City. Could I take a cab immediately and come over to the office, he was asking me agitatedly. All he would say on the phone was that the Indian Prime Minister had been shot dead in her residence by her security guards, and could I please do a fast obituary for the special morning edition? I rushed out. It felt so strange racing through the near empty streets of downtown New York; my mind going back to disjointed bits and pieces of old memories from my long years of reporting Indira Gandhi, her first tentative forays into diplomacy in Kathmandu, her bandaged nose at an election rally, her outburst of anger against officials when she had tasted a morsel of khichri from the plate of a famine-stricken child in a remote village of Palamau and found no salt in it, the shattered lady who had gone to Paunar to seek solace from Vinoba, the elephant ride to Belchi, the indomitable fighting spirit as she struggled back to power, the tantrums and histrionics as she refused to move out of her house without being handcuffed, the sudden surge of pride I had felt just being an Indian when she declared at the Washington Press Club that she leaned neither Left nor Right but stood erect… Dead? Shot by her own security guards? It must be some kind of a bad joke, I had told myself. At the newspaper office, before sitting down to write an obit, perhaps the hardest assignment of my life, I had quickly gone over the paper roll spewing out of the tickers: the first Reuter reports had said she had been shot at from three sides, later they had withdrawn the story and said only two Sikh security guards had fired at her. Even the names had sounded familiar, how could they have done it? The locale had come back in a flash: the serene sylvan stretch of pathway between 1 Safdarjang Road where she lived and 1 Akbar Road where she had her home office. She had loved it so much, walking barefoot on the dewy grass outside her bedroom, surrounded by flowering trees with birds of great variety, the flower-beds with the hum of bees.

It had all ended in these paper rolls on the ticker: She had been walking down to the office block for a television interview by Peter Ustinov when she was strafed with bullets. Just the night before she had returned from Bhubaneshwar. She had said she would shed the last drops of her blood for the country. Had she known?

Between long-distance calls to home in Delhi, already turned tense and eerie and soon to burst into sporadic flames and wanton killings, I had sat down to write an obituary. Reading the 2,000-odd words, all that my editor friend had said was, “Is this really how you feel about Indira Gandhi?” I forget what I had written, but it was one long panegyric for the leader who had suddenly passed away, leaving a big hole in my heart. At that moment I had felt no negative feelings about her.

Next day I flew back to Delhi, It was a different city from what I had last seen of it three months earlier. A city in hate and anger. A city without Indira Gandhi. I had felt I would do no political reporting any more. Who was left to write about?

Excerpted from Prime Ministers: Nehru to Vajpayee by Janardan Thakur, Eeshwar Prakashan, New Delhi