Janardan Thakur started his career in journalism with the nationalist Patna daily, The Searchlight, in December 1959. In his long and distinguished career spanning the reign of each Prime Minister since Independence, Thakur reported from the thick of some of the most momentous contemporary events at home and afar—JP’s ‘total revolution’, the Emergency, the bristling emergence of Sanjay Gandhi, the fall and rise of Indira Gandhi and then the rise and fall of Rajiv, the Kremlin of Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and Khomeini’s revolution in Iran, Ronald Reagan’s re-election in an America swinging Right, VP Singh’s ascent as a messiah with tainted magic and the rasping run to power of the BJP. Thakur’s journalism, from the very start, broke traditional moulds of reportage and writing, going beyond the story that meets the eye and into processes and personalities that made them happen. His stories on the Bihar famine of the mid-1960s and the manmade floods that ravaged the State were a sensation. He was perhaps alone in predicting defeat for Indira Gandhi in 1977 and again singular in exposing the corroded innards of the Janata Government that followed. A Jefferson Fellow at the East-West Center, Hawaii, in 1971, Thakur moved to New Delhi as a Special Correspondent for the Ananda Bazar Patrika group of publications in 1976. He went freelance in 1980 and turned syndicated columnist. In 1989-91, he was Editor of the fortnightly Onlooker, and The Free Press Journal. Thakur authored All The Prime Minister’s Men, probably the most successful of the crop of books that followed the Emergency. His All the Janata Men, the story of the men who destroyed the first non-Congress government in New Delhi, was equally successful.

Janardan Thakur started his career in journalism with the nationalist Patna daily, The Searchlight, in December 1959. In his long and distinguished career spanning the reign of each Prime Minister since Independence, Thakur reported from the thick of some of the most momentous contemporary events at home and afar—JP’s ‘total revolution’, the Emergency, the bristling emergence of Sanjay Gandhi, the fall and rise of Indira Gandhi and then the rise and fall of Rajiv, the Kremlin of Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and Khomeini’s revolution in Iran, Ronald Reagan’s re-election in an America swinging Right, VP Singh’s ascent as a messiah with tainted magic and the rasping run to power of the BJP. Thakur’s journalism, from the very start, broke traditional moulds of reportage and writing, going beyond the story that meets the eye and into processes and personalities that made them happen. His stories on the Bihar famine of the mid-1960s and the manmade floods that ravaged the State were a sensation. He was perhaps alone in predicting defeat for Indira Gandhi in 1977 and again singular in exposing the corroded innards of the Janata Government that followed. A Jefferson Fellow at the East-West Center, Hawaii, in 1971, Thakur moved to New Delhi as a Special Correspondent for the Ananda Bazar Patrika group of publications in 1976. He went freelance in 1980 and turned syndicated columnist. In 1989-91, he was Editor of the fortnightly Onlooker, and The Free Press Journal. Thakur authored All The Prime Minister’s Men, probably the most successful of the crop of books that followed the Emergency. His All the Janata Men, the story of the men who destroyed the first non-Congress government in New Delhi, was equally successful.He passed away on July 12, 1999.

WITH Vajpayee’s exit, the country was once again back to the question: ‘Who’ll be the next Prime Minister?’

The non-Congress, non-BJP parties was trying hard to find a Prime Minister. Laloo Yadav wanted the top job so desperately that he virtually gave up chief ministership and Patna to camp in Delhi, regardless of the city’s climate. But with only 20 MPs from Bihar his claim was considerably weakened. The Janata Dal had done much better in Karnataka; besides Laloo had a big opponent in Mulayam Singh Yadav who could not let another Yadav beat him to the prime ministership. Mulayam campaigned with the Left, Harkishen Singh Surjeet in the main, to sabotage Laloo. He is scam tainted (the first fodder scam disclosures had begun to come in the last days of the Rao Raj), Mulayam told the Left, besides he has treated the Communists with disdain in Bihar. He even split the CPI.

While the Yadavs quarrelled, the regional parties (TDP, DMK, AGP, National Conference) got together to form a federal front at Andhra Bhawan and announced they would support a non-BJP, non-Congress Prime Minister. Pressure mounted on the Janata Dal, then the core of the National Front, and the Communists to agree on a Prime Minister. But there was no agreeable man in sight.

In desperation, the National Front and the Federal Front leaders drove in a convoy to fall at VP Singh’s feet and anoint him Prime Minister. But VP got wind of it and fled his 1, Teen Murti Marg house. Amid high drama, the VIP convoy arrived to find VP gone. Late that evening, the NF and FF leaders met at the Orissa Bhawan and named Jyoti Basu their candidate. Jyoti Basu and his party boss, Surjeet, were jubilant-at last a Communist Prime Minister! But they said the CPM central committee would have to endorse Basu’s candidature. The next morning, the central committee shot it down; the CPM could not afford to head a government backed by the Congress Party. Jyoti Basu and Surjeet came out of the central committee meeting glum and at a loss for words. The young turks in the party -would-be general secretary Prakash Karat and Sitaram Yechury, along with the hardliners from West Bengal and Kerala, where the CPM’s main rival is the Congress-had said a firm No.

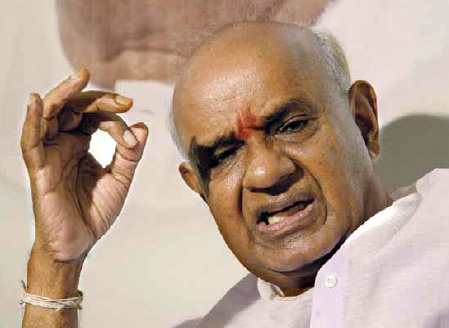

Jyoti Basu would later describe the decision as a ‘historic blunder’ but on the day that the National Front and the Federal Front were back to square one: enough MPs but no Prime Minister. Conclaves continued all day -at the Andhra Bhawan and the Orissa Bhawan, where the never-say-die mergerist, Biju Patnaik, was always up with something or the other, thinking of ten moves ahead like a consummate Grand Master. Late in the night the scene shifted to Karnataka Bhawan, where Chief Minister Gowda was camping. In the end, Jyoti Basu proposed the name of Deve Gowda, the dark horse from Karnataka. He was not even an MP, but so what? The party had done even better than expected in his state, he had handled investment opportunities extremely well after liberalisation and, most important, he did not have many enemies in Delhi. Everybody thought Deve Gowda was pliable-a weak PM. their man, everybody’s man. Little did they know…

At that point, Gowda had even despaired of ever being able to attain his ambition of becoming the chief minister of Karnataka. The swarthy homespun leader from Hassan, who often described himself as a hall gowda (a rural farmer) had come close to his goal twice, but both times he was thwarted by the man who had played the most crucial role in his political career: Ramakrishna Hegde. In 1985, Gowda was the frontrunner for the chief minister’s post He had worked hard to build the party machinery in the state, while the suave urbane Hegde was honing his national image as the general secretary of the Janata Party. Hegde had not even fought the assembly elections, but after the victory of the party he had suddenly flown in from Delhi and snatched the trophy, and Gowda had to content himself with the irrigation portfolio. The strains between the two soon turned into mutual hatred and then all-out war.

Gowda and Hegde were two very different people: Hegde was suave and stylish, Gowda had rustic simplicity. Hegde surrounded himself with a cabal of cronies who not only extolled him as the paragon of virtue but even portrayed him as the future Prime Minister. Gowda looked upon Hegde as a Johnny-come-lately who had cornered all the glory. Things came to a head in 1988 when Hegde ordered an inquiry into some land grab scandal involving Gowda who had resigned from the Cabinet but stayed in the party. Then he started taking out one skeleton after another from Hegde’s cupboard, with the investigative expertise of who else but Subramaniam Swamy, the ‘evil genius’ of so many politicians and Prime Ministers.

Before Swamy had set his evil eye on Hegde, the chief minister had initiated a Lok Ayukta inquiry into Gowda’s alleged land deals, and Gowda in turn had joined the enemies of Hegde to do him in. Gowda could have become the chief minister in 1988 but was thwarted once again when Hegde helped to tilt the balance in favour of SR Bommai, from the northern Karnataka district of Dharwar, Bommai.

That was the beginning of the darkest ever spell in Gowda’s political career. He had gone over to Chandra Shekhar’s Samajwadi Janata Party and was virtually wiped out of the political scene. In December 1989, he fought from two assembly constituencies and lost in both-Holenarsipura and Kanakapura. A stunning blow for a man who had never lost an election since be got into the assembly in 1962. Desperate to rehabilitate himself, Gowda fought the 1991 Lok Sabha elections and campaigned frantically, even going so far as to sometimes ride pillion on Dr. Swamy’s motorbike.

STRANGE had been the beginnings of Gowda’s career in politics. It was the result of a small time factional war between two veteran Mysore politicians. Sahukar Channaiyya was a rich man. He had dose links with Jawaharlal Nehru. His rival was a politician called AG Ramachandra Rao, a stalwart freedom fighter and the first elected education minister of Mysore. Channaiyya’s greatest ambition was to finish Rao. With his links in high places, he managed to deprive Rao of a party ticket in the assembly elections of 1962, and set up Deve Gowda as a candidate. Our humble farmer, Gowda, had done a diploma in civil engineering and was a PWD contractor making roads, digging tanks. He had become a member of the taluka board. After Ramachandra Rao was denied the Congress ticket, it was given to one Gowda who also happened to have the same initials as our protagonist: HDD. But he was ‘Dodda’, not Deve Gowda. In those days it was considered a dream to defeat a Congress nominee, but unlike Deve Gowda, Dodda was an outsider to the constituency. Deve Gowda had the support of people who still wielded great influence in those days: teachers.

That was the first phase of Gowda’s politics-“the phase of the lamb”, as one of his old associates put it. In the second phase, “the lamb started turning into a tiger. After his first two terms as MLA, he had started coming into contact with bureaucrats of his caste who made him aware of what power is. They told him he must have a house in Bangalore, be in the city and to keep himself abreast of what was happening in the government, otherwise it was difficult to make an impact in politics. By 1982, Gowda had got into the swing of politics-“the man-eater phase” in the words of his old friend. He was no longer just a ‘simpleton’, he had learnt all the ‘arts and tricks of the trade.’ Like so many other ambitious politicians, Gowda had great faith in astrology. In 1967, he had gone to a renowned fortune-teller of Mysore, Achyuta Shastri, who told him: “You will go to the highest post in India. But it is short-lived.”

Gowda first came to the Lok Sabha as one of the two MPs of Chandra Shekhar’s Samajwadi Janata Party, the other member being Chandra Shekhar himself. Gowda had requested the Lok Sabha secretariat that he be given a seat at the back. In the three years that he remained MP, he left no impression on the House, but he established a connection which was to play a vital role in his future political career. The connection was Prime Minister PV Narasimha Rao. Gowda was a frequent visitor to 7 Race Course Road, and it was as the political understudy of Rao that he took one of the most vital decisions of his career: to make up with Hegde. Without having merged once again with the Janata Dal, and without Hegde’s blessings he could never have become the Chief Minister. Gowda, his friends say, has a great talent for weeping: “If he wants to win over someone, he would submit to him and weep.” That is what he did to win over Hegde. He submitted himself to him, called him his elder leader and wept.

POLITICS breeds strange bedfellows. In the Janata Party, the two had been out to wreck each other’s reputation. If Hegde had been shorn of his halo of value-based politician, it was Gowda’s doing. If Gowda was driven into Chandra Shekhar’s arms, the full credit went to Hegde. Now suddenly Gowda was begging Hegde to let bygones be bygones. Hegde showed his magnanimity and embraced him. “Let’s forget about the past,” Hegde told reporters. “Anything is possible in the permutations and combinations of politics”, said Gowda with a chuckle. He was quite happy as long as Hegde played his role on the national scene. Gowda himself had no intentions of ever going beyond the boundaries of Karnataka. Or so he had said. Was it only destiny’s impish game?

Few could have foreseen the role that Gowda’s Rao connection was to play in the political drama. It was only the Rao-Hegde connection that was talked about, and in the post-election scenario Hegde had become a persona non grata with the victorious anti- BJP elements which had ganged up for power.

Significantly, Narasimha Rao had planted the seed of ambition in Gowda much before the NF-LF leaders had even thought of his name. Even while they were running after Jyoti Basu and the Raja of Manda with the crown in their hands, Rao had conveyed his desire through an emissary. When the suggestion was first put to him, Gowda had laughed: “What? Me? Prime Minister of India?” His dismay was understandable. But it soon turned to Why Not? What seemed an immediate necessity was a quick trip to the Gods down south. He returned to Delhi a changed man: a man of destiny.

How would he fare? How well could he manage the contradictions? He was a dark horse. Nothing about him could be predicted with certainty. Charisma was the last thing that he had, but then Rao had shown how it was the least part of being the Prime Minister. During his brief tenure as chief minister, Gowda had shown some of his strengths: he was a down-to-earth man, very pragmatic hard working man, free of any dogmatic beliefs. He had tremendous-“he waits like a lizard, without moving and then he would strike,” was how one of his old friends described Gowda. Another thought he was like a cuckoo who would put his egg in others’ nest to be hatched. Gowda knew the art of winning people, he had won over even his enemy He had been only too willing to adjust with new situations. He had shown there was no contradiction in being a ‘humble farmer’ and a promoter of the country’s new economic policies.

As the Prime Minister, Gowda showed his intentions early. On his second day in office, he got his old foe-turned-friend Ramakrishna Hegde expelled from the Janata Dal on charges of anti-party activity. He thereby risked losing the Janata Dal government in Karnataka, but so what? Hegde had too long been a thorn in his side, now was the time to teach him a lesson. He had waited long for this day-‘like a lizard’! He sweetly accommodated all of Laloo’s Yadav’s men in his Cabinet, drove to the Bihar Bhawan and got Laloo, then the president of the Janata Dal, to sign the expulsion order. It is not for nothing that they say Gowda presided over the demise of the Janata Dal. He knocked out the party in his home state. A year later, he would manipulate the ouster of Laloo Yadav from the party (after the first fodder scam chargesheet) and decimate the JD in Bihar too.

It was a time of political discoveries: If the new Prime Minister was discovering the India beyond Karnataka, the rest of India was discovering the villages of Hassan, and were they not getting wiser for it? There was of course the question flung in your face the very first day the man from Hardanahalli took over: “Does a Prime Minister have to know what is CTBT?” Asking the question was a veteran member of Parliament, and for a moment I did not know what he was talking about. The question was so abrupt that even I did not know what CTBT was all about. It took a while to understand what he was getting at. The new Prime Minister had not known what the acronym stood for. But then did he have to know? Does a Prime Minister have to be a know-all like, say, the gentlemen of the Indian Administrative Service? Why then would the PM have so many IAS and IFS officers around him? The MP was being unfair, I decided. We had to give the man from Hardanahalli a little time. Was he not saying himself what a long way he had come?-from a petty contractor of roads and bridges to the country’s top job! Sure enough he would pick up, if he only tried.

And could anyone say he was not trying? God, he was trying so hard he was hardly sleeping, or sleeping so little that he was falling off to sleep in the wrong places, at the wrong time. A Delhi tabloid on Better Living had carried a story on the growing problem of insomnia: ‘Sleepless in the Capital’ ran the headline and atop it, as an illustration, was the picture of Prime Minister HD Deve Gowda snoozing away at a function. Which only showed how hard he was trying, and the more the people said he could last very long the harder he had to try. I had thought the man behind him in the picture, the Marxist leader Harkishen Singh Surjeet, ought to have shown sympathy for the harried man rather than the sardonic smile on his face.

GOWDA’S reason for being so harried? Which Prime Minister had ever had so many masters to serve? There was first the Saheb, Narasimha Rao, to be kept happy, for not only was the entire Gowda circus dependent on the old man’s goodwill but there was also the personal gratitude that the Prime Minister owed to him. Without Rao’s blessings and advice he could never have become the chief minister in Karnataka, without his advice and consent he could never have shot up to the Prime Minister’s chair. How Gowda would have felt if VP Singh had accepted the crown is hard to imagine, but he had waited at the Karnataka Bhawan knowing that it would not be VP Singh. Not because the Raja had taken sanyas but because he must have known all the time that he would be the last person to get a nod from Narasimha Rao.

Like his friend, philosopher and guide, Narasimha Rao, Gowda was forever on the razor’s edge. He had to keep too many people happy, which was like keeping dozens of balls in the air. The contradictions were sharp; he had not only to please Narasimha Rao but also those who were out for Rao’s head. VP Singh, still the archangel of the Janata Dal, was pushing him to act against the corrupt and the malfeasant, and his other Guru, Chandra Shekhar, was whispering his own mantras into his ear. Then there were the self roclaimed king-makers in the Janata Dal and a dozen other parties, ranging from Laloo Prasad Yadav to Chandrababu Naidu to Harkishen Singh Surjeet, all expecting adequate returns for their support. Laloo Yadav foisted Taslimuddin on Gowda, the first albatross round his neck. But much before the Prime Minister was even aware of the worthless coins he had landed up with, he had got down to settling his scores with Hegde. From Laloo to VP Singh to Bommai, he had gone pleading for action against the man, a strange spectacle for people in Delhi. But it was no surprise to those who were better acquainted with Gowda’s politics-it had only one reference point: Ramakrishna Hegde. During his first speech in Parliament, Gowda had made it a point to say that he was not a vindictive man. Only later did the people understand why he had made so much of his non-vindictiveness.

BY the time the Prime Minister was through with Karnataka, muck was piling all around him. The great sultans who had joined his government thought they were laws unto themselves, and were shooting their mouths one after another. Mulayam Singh Yadav made his policy statement on Ayodhya and Kashmir, without bothering to consult the Prime Minister. While Yadav was promising maximum autonomy to Kashmir and setting the government’s policy on Ram Janmabhoomi, even the dubious fresher in the government, Taslimuddin, was declaring that the idol of Ram would be removed from its present site in Ayodhya. What nobody could miss was the way the Gowda government kept expanding, week after week. Some who were chosen to be ministers of state refused to be sworn-in because they thought they deserved to be full ministers. Those who sulked and stayed out were appeased, which in turn encouraged others to do the same.There were different versions on why Gowda did not take Maneka Gandhi into the government, as many had thought he would. One version was that Gowda thought she was too overrated as ‘Ms Green’, another that she was too much of a Hegde friend to be acceptable to him. Whatever the reason, her exclusion was to prove a headache for Gowda. She claimed the Prime Minister had offered a berth to her and it was she who had rejected it because the government was ‘so full of criminals and undesirables’. Laloo Yadav had hit back, for he could not stomach what Maneka had said about his favourite nominee in Gowda’s ministry, Kanti Devi. “She (Maneka Gandhi) says Kanti Singh was working for a nautanki. It is a matter of shame. If people from cities say such things about people from villages, then there will be a revolt.” Maneka launched such a tirade against the Gowda government that he had little choice but to have her expelled from the party. He did not have much problem, as the party president, Laloo, was himself dying to ‘finish the city girl’. Maneka was out, but she had left the Gowda government stinking with the Congentrix deal.

Enter the comrades. It was the first time that the communists had come into a government at the Centre. The veteran parliamentarian, Indrajit Gupta, and his able colleague from Bihar, Chaturanan Mishra, both of the CPI, became Cabinet ministers, Gupta with Home portfolio. The Marxists had decided they would stay away and have the best of both worlds, privileges as well as prestige-all without any responsibility. The entry of the communists was hailed as a “new strength” for the Gowda government, which was partly true, but the strength was offset by the almost daily crisis created by the off-the-cuff pronouncements of the new Home Minister, Gupta. With his dominating personality and background as a stalwart of the opposition benches, he created waves every time he made one of blunt statements, which was ever so often that some started calling him the ‘Angry Old Man’ of the government.

Deve Gowda was in his worst jitters when Indrajit Gupta decided to speak out his mind on the Congress party and its leader, Narasimha Rao. The best thing the Congress could do, he said, was to dump their president, Narasimha Rao. Very apt observation, many thought, but the anger it caused in Rao’s camp and the threat that it brought forth shook the coalitions to its roots. Gupta saved the situation by retracting, but the episode did not pass without showing how utterly vulnerable the coalition was.

Gowda was learning fast. As some of his friends said, look deeper and you would find “an ambitious, cunning, intelligent man.” He was being accused of being parochial and he was visiting Bangalore so often that some even started calling him the ‘Prime Minister of Karnataka”. Gowda started making efforts to ‘expand his horizons’, especially towards Mulayam’s fiefdom. He befriended Ajit Singh to get close to Mahendra Singh Tikait, the peasant leader of Western UP. He addressed a rally in Lucknow where Mulayam was not even invited. Gowda used his minister and right-hand man, CM Ibrahim, to build up his own image as a friend of the Muslims-again a bid to undercut Mulayam’s base. But he was clearly not getting anywhere in the North, despite his desperate efforts to speak some sentences in Hindi, despite his efforts to project himself as a humble farmer.

Gowda depended heavily on advice from Surjeet, whose influence he would use later to throw Laloo Yadav out of the Janata Dal during Gujral’s days as Prime Minister. But Gowda’s most Machiavellian plots were reserved for the Congress boss Sitaram Kesri, on whose support his government rested. From the very start, Gowda sidelined and ignored Kesri. He chose to liaise with the deposed and sulking Narasimha Rao instead, met him almost every week, sometimes making these meetings known to Kesri. When it came to dealing with the parliamentary wing of the Congress, Gowda again chose Pawar over Kesri.

Tensions between the two mounted. Kesri thought Gowda was playing games with him. He even blamed the Prime Minister for getting the investigating agencies-the CBI and the Enforcement Directorate-to open cases against him. Suddenly Kesri was in the thick of these major cases-one relating to the murder of Dr. Tanwar, Kesri’s personal physician, nearly a decade ago, another relating to FERA violations committed by the Congress when Kesri was AICC Treasurer, and yet another concerning disproportionate assets of the Kesri family. Kesri alleged that Gowda was using the CBI, then under Joginder Singh, a Karnataka cadre IPS officer personally chosen by Gowda to head the CBI, to get at the Congress President. Kesri called Gowda nikamma aur firqaparast (a wimp and a communal man) and pressed the United Front to get rid of him. Kesri wanted another Prime Minister or polls, but the UF said No.

Vijaya Bhaskara Reddy, Karunakaran and Sharad Pawar had called on the Congress chief. Karunakaran was worried about being chargesheeted in the import of Palmolein oil case. Kesri kept saying it was a “Phansao” government. Ghulam Nabi Azad was being probed for wetleasing aircraft during his tenure as civil aviation minister, Santosh Mohan Dev for a Steel Authority of India Ltd case of mysterious donations, and Karunakaran for the oil case. On March 30, a triumphant looking Kesri had entered the AICC office saying, “Maine kar diya, maine kar diya! (I have done it, I have done it.)”

“Kya kar diya aapne?” a colleague had asked.

“Withdraw kar diya, support withdraw kar diya… ”

“Bandar ke haath mein talwar (a sword in the hands of a monkey!)” a Congress MP had remarked.

KESRI was suddenly acting as though he had already become the Prime Minister himself. Five hours after delivering the letter to President withdrawing support to the government, he was answering questions on the budget-Ab sochenge…Exim policy Pranabbabu se poochho…

Asked if he saw himself as the Prime Minister he said: “Dekhiye, koi aadmi aise kehta hai, agar banna bhi ho? (Let’s see. Does anyone say this, if he has to become the Prime Minister?).”

But as Kesri hung on to his threat of forcing another election, the UF softened and prepared to ditch Gowda. Even as the outgoing Prime Minister was making his bitter “I shall rise from the ashes” speech in Lok Sabha, the United Front bigwigs were meeting at the Andhra Bhawan, hosted by Chandrababu Naidu, who was among those insisting that there must not be another election. Gowda was sacrificed. His government fell in the face of the grudging, yet decisive joint vote of the Congress and the BJP. The final count, on the midnight of April 11, was 388 votes against the confidence motion and 190 in favour.

A great believer in tantra, Gowda had entered 7 Race Course Road even while Rao was living there because later there would not be a propitious enough time. Rao was gracious enough to let the Gowdas in and perform their Grihapravesham-but obviously the stars were not with him for too long. He had lasted 10 months and 10 days.

Excerpted from Prime Ministers: Nehru to Vajpayee by Janardan Thakur, Eeshwar Prakashan, New Delhi