- Cover Story

- Governance

- Globe Scan

- Corruption

- State Scan

- Talk Time

- Cover Story

- Governance

- Globe Scan

- Corruption

- State Scan

- Talk Time

Recent Posts

© Copyright 2007 - 2023 Gfiles India. All rights reserved powered by Creative Web INC.Globe Scan‘Abeplomacy’ offsetting Japan’s isolation in Asia

A lot is riding on Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s push to export nuclear technology abroad. As Abe visits New Delhi on the occasion of India’s Republic Day, we examine the nuclear component of ‘Abenomics’ infrastructure-exports growth strategy

Jeff KingstonFebruary 9, 201410 Mins read105 Views

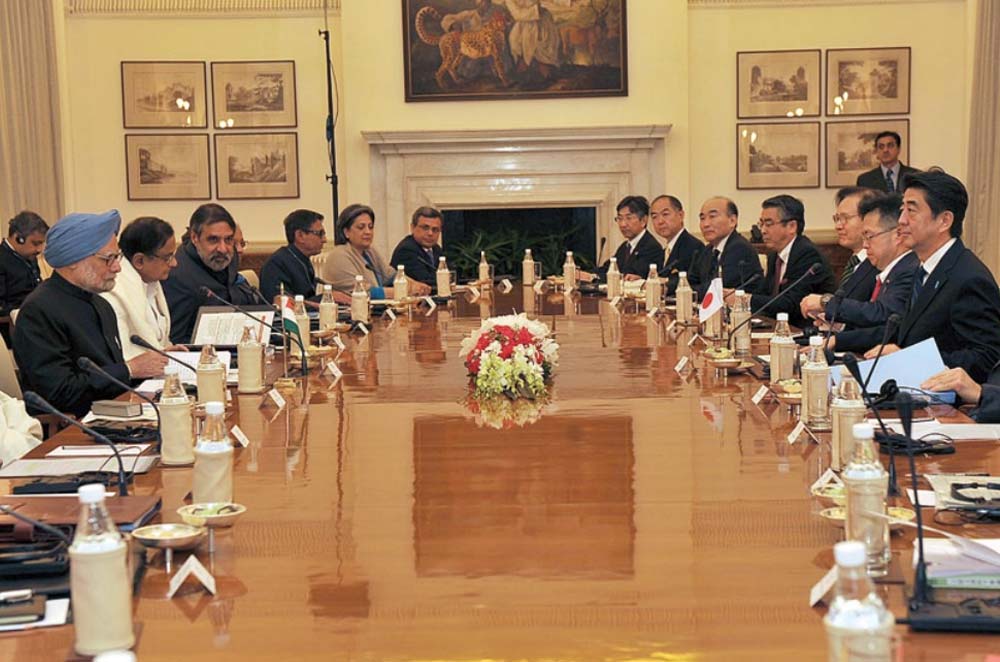

Shinzo Abe, Japan’s prime minister (left) and Manmohan Singh, India’s prime minister, shake hands during a news conference at Hyderabad House in New Delhi, India, on Jan. 25, 2014.Written by Jeff Kingston

Shinzo Abe, Japan’s prime minister (left) and Manmohan Singh, India’s prime minister, shake hands during a news conference at Hyderabad House in New Delhi, India, on Jan. 25, 2014.Written by Jeff KingstonPRIME Minister Shinzo Abe was in New Delhi recently to celebrate the 65th anniversary of the founding of the Indian Republic. His presence speaks volumes about closer diplomatic, security and economic ties and, at least from Tokyo’s perspective, a common agenda on responding to the rise of China. India remains ambivalent, pursuing a shrewd hedging strategy rather than siding with either Beijing or Washington/Tokyo, eager to maximise concessions from all sides.

“The Emperor visited India last month — a huge symbolic event — and now Abe has been invited to be the chief guest at the Republic Day celebrations on Jan. 26 — no other Japanese prime minister has been invited to this before — an invitation extended only to close friends and partners,” says Punendra Jain, professor of Asian Studies at Adelaide University in Australia. “This symbolises their closer and evolving political and strategic relationships. Of course, the elephant in the room is China.”

Tensions with China and South Korea have spiralled upward over the past year and thus “Abeplomacy” seeks to offset Japan’s isolation in East Asia by nurturing closer ties with the member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and India. Warming ties with New Delhi marks a sharp turnaround from 1998 when Japan imposed economic sanctions on India (and Pakistan) for conducting a series of nuclear tests. These sanctions were lifted in 2001, at Washington’s behest, to reward their support for the US-led “war on terror.” Since 2003, India has been the largest recipient of Japanese economic assistance, and economic ties are growing due to the 2011 Comprehensive Economic Partner-ship Agreement. Bilateral trade in 2011-12 reached $18.43 billion, up 34 per cent from the previous year, but remains modest given the $334 billion in Sino-Japanese trade in 2012.

Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and the Prime Minister of Japan, Shinzo Abe, at the delegation level talks, in New Delhi on January 25 “The Indian nuclear tests of 1998 marked the lowest point in bilateral relations, as Japan reacted strongly to the nuclearisation of the subcontinent,” says Harsh Pant, professor of international relations at King’s College London. “Tokyo suspended economic assistance for three years as well as put on hold all political exchanges between the two nations. This strong reaction from Japan was in many ways understandable, given that the Japanese are the only people to have experienced attacks by nuclear weapons.”

The ShinMaywa plane deal is seen as a significant boost to growing bilateral defence cooperation. To skirt the existing ban on military exports, a stripped down “civilian” version of the plane would be sold without the Identify Friend or Foe system. The Indian Navy is keen to acquire this aircraft and plans to equip it with an Israeli IFF system. Lifting the arms export ban to help Japan’s defence sector industries is an Abe priority in 2014.

However, Pant explains, “many in India saw the Japanese reaction as hypocritical for apparently brushing aside India’s genuine security concerns even as Japan enjoyed the security guarantee of the US nuclear umbrella.”

Japan, as the sole nation to suffer a nuclear attack, has strongly opposed nuclear proliferation on principle, and as such been an outspoken critic of India’s nuclear weapons programme and refusal to join the 1968 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) or 1996 Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT). However, India also bases its non-participation in these regimes on principle: the nuclear weapons possessing nations granted themselves a monopoly on nuclear weapons and have not followed up on pledges to eliminate their nuclear arsenals.

FROM the Indian government’s perspective, these non-proliferation agreements created an exclusive club of status quo powers that left their nation marginalised and vulnerable. The 1962 border war with China was an unmitigated disaster for Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s friendly diplomacy toward Beijing, based on the false assumption that the two nations shared a common agenda and could cooperate to reciprocal advantage. The comprehensive defeat was also a shock for the Indian armed forces, exposing inadequate military preparation. Upping the ante China then detonated a nuclear device in 1964, sending shock waves through India’s security community and ensuring that it would follow suit. In 1974, India conducted its first nuclear test, dubbed “Smiling Buddha,” and its last tests in 1998. India maintains that its nuclear arsenal is for deterrence only and has declared a nuclear no-first-use policy.

In 2008, the International Atomic Energy Agency reached an agreement with India to allow it access to India’s civilian nuclear reactors. This agreement paved the way for the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG), under intense US pressure, to grant India a waiver in 2008 allowing it access to civilian nuclear technology and fuel from the 48 member states. Since the waiver was granted, India has reached an agreement with the US and France, among others, because they regard India as one of the most promising markets for nuclear reactor exports. Ironically, India’s 1974 nuclear test triggered the establishment of the NSG, but now Washington has abandoned the sanctions regime it once imposed and US President Barack Obama backs India’s membership in the group.

Let’s make a deal

The 2008 US-India Civil Nuclear Agreement brokered by the administration of President George W Bush has become the template for subsequent agreements, meaning that India’s unilateral pledge to refrain from nuclear tests has been accepted as sufficient guarantee. Until then, the NSG only cooperated with nations that signed the NPT. Under the terms of the agreement, in the event that India does conduct a nuclear test, any decision to terminate the accord and cut access would only be invoked after a year of consultations.THIS is where Japan comes in. Exports of nuclear components and technology, as well as conventional arms, are potentially key elements of “Abenomics” and much is riding on the outcome. In 2013, Abe concluded Japan’s first nuclear reactor export agreement with Turkey for $22 billion and others are pending with Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, while the Prime Minister has also lobbied governments in Central Europe, Vietnam and Indonesia. This is a remarkable turnaround from 2011 when the prospects for post-Fukushima Japan relying on nuclear energy, let alone exporting it, looked unlikely.

Three major nuclear vendors have bagged contracts in India estimated at roughly $60 billion, but the final price will probably balloon given a history of cost overruns. For example, Finland’s order for Areva’s Evolutionary Pressurized Reactor (EPR) has nearly tripled in cost to €8.5 billion from the original price tag of €3 billion and India has ordered six of these reactors. Each of the major vendors feature significant Japanese stakes — GE/Hitachi, Westinghouse/Toshiba and Areva/Mitsubishi — and all produce key reactor components in Japan. As such, they need the Japanese government to agree to the NSG waiver and hammer out an accord with India. Abe is keen to cut a deal despite reservations within his party and ruling coalition, and has the numbers in the Diet to ignore public opposition as he did when ramming the notorious secrecy legislation through the Diet in December.

Negotiations have stalled since 2008 mostly due to Japan’s insistence on India relinquishing its right to conduct nuclear tests and an immediate cessation of cooperation if India violates its self-imposed moratorium. Japan also opposes India’s desire to reprocess spent fuel. However, a recent pact with Turkey has a provision that allows it to enrich uranium and extract plutonium if agreed in writing, paving the way for exports of relevant Japanese technologies, so it is hard to imagine that India will settle for less.

Furthermore, the Japanese government wants India to formally restate its commitment to India’s no-first-use nuclear weapons policy and support for non-proliferation in the pact. India’s position remains clear: Japan should accept the same deal as the US and other NSG members that don’t include such provisions.

Discussions were suspended after the Fukushima nuclear reactor meltdowns in March 2011, but resumed in May 2013. At the end of December, negotiators had not yet bridged differences on civilian nuclear cooperation or the sale of US-2 amphibious search-and-rescue military aircraft produced by ShinMaywa. The plane deal is seen as a significant boost to growing bilateral defence cooperation. To skirt the existing ban on military exports, a stripped down “civilian” version of the plane would be sold without the Identify Friend or Foe system. The Indian Navy is keen to acquire this aircraft and plans to equip it with an Israeli IFF system. Lifting the arms export ban to help Japan’s defence sector industries is an Abe priority in 2014.

“Whether the two nations are able to sign the pact during Abe’s January visit would depend on how much risk he is willing to take on the nuclear front and whether it would be a good idea for him to sign a deal with a lame-duck government in Delhi,” Pant says. “The Indian government would not be able to deliver any significant change in its posture as elections are round the corner and they can’t dilute their traditional stand on the CTBT.”

WHILE postponement is possible, Jain believes that “the deal is going to go ahead. I don’t see much difference between the BJP (Indian People’s Party) and Congress as far as Japan-India relations are concerned. If anything, BJP might seek closer ties with Japan.”

Jain adds, “As you know, in India, the agreement will be welcomed in all quarters; strategic analysts, former diplomats and military leaders are writing strongly in favour.”

Dissensus

But not everyone agrees. Japan’s first lady, Akie Abe, who has openly expressed opposition to her husband’s support for nuclear energy exports, told a Dec. 29 television programme that, “It remains anybody’s guess if proper maintenance will be provided overseas. I wonder how Japan would cope in case of an emergency.”According to opinion polls, her doubts are shared by a majority of Japanese, including the mayor of Nagasaki who criticised the deal in August.

Citizens in India worry, too. “(The deal) pushes India’s ill-conceived nuclear expansion ahead, creates a bad precedent of rewarding India for its nuclear tests while others face sanctions . . . and the whole dynamics of India, Japan and US cozying up to contain China (will) destabilise Asia,” says PK Sundaram from the Coalition for Nuclear Disarmament and Peace, India.

He acknowledges that Indian parties across the political spectrum support nuclear energy, but believes that large, sustained public protests against nuclear reactors, especially near a new nuclear plant sited at Kundankulam in Tamil Nadu, represent fallout from Fukushima and widespread scepticism about nuclear safety.

Pankaj Mishra, an acclaimed writer from India, chides the Indian government for blaming “an unspecified ‘foreign hand’ for the (anti-nuclear) protests. Never mind that the much-despised foreign hand helped build the Kudankulam plant, along with much of India’s nuclear infrastructure.”

MG Devasahayam, a former IAS official, asked me whether Abe would approve the deal. I said yes, venturing that Abe is pro-India. He replied that he shouldn’t. “It is morally inappropriate for a country that has suffered the worst from nuclear holocausts in war as well as in peace to supply nuclear reactors and equipment to an over-populated country like India with limited land and water resources,” Devasahayam says. “India needs electricity that is cheap and affordable whereas nuclear power is expensive. If all costs — construction, commissioning, operation, decommissioning and safe storage of spent-fuel — are honestly factored in, nuclear power is way costlier than any other source of electricity.”

Exports of nuclear components and technology, as well as conventional arms, are potentially key elements of “Abenomics” and much is riding on the outcome. A recent pact between Japan and Turkey has a provision that allows it to enrich uranium and extract plutonium if agreed in writing, paving the way for exports of relevant Japanese technologies, so it is hard to imagine that India will settle for less.

THE worries that “Japan’s long-term relationship with India will be seriously jeopardised once the Indian public comes to realise the ill-effects of nuclear power on their life, livelihood, environment and future generations.”

AV Ramana, a nuclear physicist based at Princeton University, agrees that nuclear energy does not make sense for India due to the high costs and safety concerns. In his book “The Power of Promise: Examining Nuclear Energy in India,” Ramana argues that nuclear energy is inappropriate for India on environmental, economic and technological grounds.

“Japan, which is currently facing tremendous democratic opposition to restarting nuclear reactors within the country, is considering exporting nuclear reactor parts to a country where, again, there is significant opposition to nuclear power, a history of failure, poor technology choices and a lack of organisational learning,” Ramana says.

He cites the continued emphasis on breeder reactors, abandoned by other nations due to cost and safety concerns, as evidence of institutional myopia. “Because of its centralised character and the huge costs involved, nuclear power cannot play a significant role in solving the energy needs of the vast majority of India’s population (and) only brings with it two of the familiar — and so far insoluble — problems associated with nuclear energy: susceptibility to catastrophic accidents and having to deal with radioactive waste that stays hazardous to human health for millennia,” he says.

“Their reasons for such opposition are not difficult to discern. In the aftermath of March 11, 2011, people near an existing or proposed nuclear reactor can — and do — imagine themselves suffering a fate similar to those of the inhabitants of the areas around Fukushima,” he says.

These anxieties appear warranted after A Gopalakrishnan, former chairman of India’s Atomic Energy Regulatory Board, revealed in April 2013 that the Russians used substandard components in building the Kundankulam reactors, planting a potential time bomb in southern India.

Nuclear liability of suppliers is a key issue because it’s a potential deal breaker. According to Arun Jaitley, the BJP opposition leader in India’s Upper House, the issue of liability remains murky despite government efforts to finesse the issue. Nuclear vendors are relying on a clause in contracts signed with the Nuclear Power Corp. of India that is designed to insulate them from any right to recourse, but Jaitley argues that legally this won’t stand. Without an ironclad waiver on liability, however, most nuclear suppliers won’t proceed. As Ramana says, “the nuclear industry doesn’t like this business of being liable for anything at all.”

Rivals suppliers in Russia and South Korea might capitalise on Japan’s misgivings. Seoul signed a civilian nuclear agreement with India in 2011 and earlier this month Park Geun-hye visited New Delhi to explore nuclear prospects. And then there is the geo-strategic angle; China recently announced it would fund and build a nuclear plant in Karachi, Pakistan — India’s arch-enemy. The pressures on Japan from the global nuclear industrial complex are also intense, reinforced by lucrative contract awards to consortium involving Japanese firms, including the GE/Hitachi nuclear project in Gujarat, where the presumptive next Indian prime minister, Narendra Modi, is now chief minister.

Abe, the pitchman-in-chief, is determined to seal the deal worth tens of billions while millions of fingers are crossed that his gamble doesn’t lead to “Abegeddon.”

Jeff Kingston lives in Tokyo, teaches history at Temple University Japan. “Contemporary Japan” (Wiley-Blackwell, 2012) is his most recent book.

Written byJeff Kingston

Jeff Kingston lives in Tokyo, teaches history at Temple University Japan. “Contemporary Japan” (Wiley-Blackwell, 2012) is his most recent book.

Recent Posts

Related Articles

Globe ScanThe US Elections 2024: small number of voters in a few key states will decide the fate of Biden and Trump

Written by Gfiles Editor By Ashe N Ayers If you don’t know US...

ByGfiles EditorJuly 21, 2024Globe ScanFive billion passengers and earning is $6.14 per passenger claims Willie Walsh, Director General IATA

Written by Special Correspondent Willie Walsh Director General IATA presented a report at...

BySpecial CorrespondentJune 3, 2024Globe ScanIs Netanyahu, PM Israel, under pressure to resign?

Written by Gfiles Editor Iran’s unprecedented attack on Israel on April 14, in...

ByGfiles EditorMay 13, 2024Globe ScanThe bear flexes muscle

Written by Nivedita Kapoor IN 2016, Russian President Vladimir Putin announced the project...

ByNivedita KapoorMay 5, 2020 - Governance

- Governance