- Cover Story

- Governance

- Globe Scan

- Corruption

- State Scan

- Talk Time

- Cover Story

- Governance

- Globe Scan

- Corruption

- State Scan

- Talk Time

Recent Posts

© Copyright 2007 - 2023 Gfiles India. All rights reserved powered by Creative Web INC.Globe ScanThe bear flexes muscle

As President Vladimir Putin faces one of the most critical challenges of his presidency—the Covid-19 pandemic—he will have to determine an effective way to advance foreign policy goals amid the crisis. This would entail balancing the strategic relationship with China, dealing with a growing bipolar rivalry, and its impact on foreign policies of other countries

Nivedita KapoorMay 5, 20209 Mins read363 Views

Written by Nivedita Kapoor

Written by Nivedita KapoorIN 2016, Russian President Vladimir Putin announced the project of ‘Greater Eurasia,’ a partnership stretching from Atlantic to the Pacific and encompassing the countries of Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the European Union (EU). Despite the fact that Europe will also form a part of its Eurasian vision, it is a departure from the post-Soviet ambitions of establishing a Greater Europe from Lisbon to Vladivostok.

The cracks in the relationship with the West were building for some time, characterised by a deep dissatisfaction with the eastward expansion of NATO, and US’ unilateral military actions in various parts of the world, as it became clear that Russia did not accept the new world order that emerged at the end of the Cold War. The 2014 Ukrainian crisis and the resulting breakdown of ties with the West have led to the conclusion that Russia is no longer looking at a future that includes integration with it.

While the European vector of Russian foreign policy remains important, the debate about Russian identity has now turned its focus towards the century old idea of Eurasian-ism. The concept looks at the geographical location of Russia as bestowing a unique position on the country and building its identity—that as a bridge between Europe and Asia.

This comes a few years after the much-publicised pivot to the East, for which the 2012 APEC summit in Vladivostok was considered to be the key event in heralding its launch. The focus on Asia-Pacific, which has been emerging as the new power centre in global affairs, was a chance to build a multi-vector policy with an increasingly important region, while also seeking to fulfil domestic economic development goals, especially in the Russian Far East.

In recent years, as the relations with the US and Europe have deteriorated, the strategic partnership with China has gained significant ground, with the latter emerging as the key partner for Russia. The Putin period has also been characterised by an attempt to build multilateral ties, including with non-Western groupings like BRICS, SCO, ASEAN, CSTO, RIC and most importantly, EAEU. It already occupies a permanent seat in the UN Security Council and believes the multilateral organisation should bear the ‘primary responsibility for maintaining international peace and security.’

While a significant amount of debate has focused on Russian attempts to interfere with electoral processes in the West, and the use of ‘Private Military Contractors (PMCs)’ in Africa and Middle East, it is important to see how these actions fit into the broader strategy, and whether their eventual impact has been a net positive or negative for Moscow

CONDUCT OF RUSSIAN POLICY

Based on the above discussion, it is clear that Russia has engaged itself in the task of building a new identity after the collapse of the Soviet Union, which stripped it off its superpower status. Since stabilising its economic situation in the 21st century, Moscow has turned its attention to expanding its foreign policy influence. The actions of the Russian leadership have revealed their intention to restore their country’s position as an important player in global affairs, and a steady pursuit of the aim of being a great power.

While a significant amount of debate has focused on Russian attempts to interfere with electoral processes in the West, and the use of ‘Private Military Contractors (PMCs)’ in Africa and Middle East, it is important to see how these actions fit into the broader strategy, and whether their eventual impact has been a net positive or negative for Moscow.

In terms of an overall strategy, Russia has for the large part focused on preserving its national interests, followed a broadly pragmatic foreign policy with a desire to establish itself as a pivotal power in global affairs, and expand Russian influence and repudiate Western values. Whether its actions have eventually led to achievement of its own goals has to be decided on a case-to-case basis, rather than a sweeping assessment of an overarching policy.

THIS is because of Russia’s current position as a middle power in the world system, and the fact that its actions remain constrained by its own economic capacity and strength. While it remains a nuclear power, major arms exporter, and permanent member of the UN Security Council, its economic strength and global outreach leave a lot to be desired.

It is between its ambitions and actual capacities on the ground that one can find the rationale behind Russia’s foreign policy actions. While its traditional strengths have lent it to become an important player in certain regions, the same has not been true of other regions where Russia has struggled to present itself as an important player.

For instance, Russia has been credited with using its limited resources to its maximum capacity in the Middle East, where its intervention in Syria has made it the power to reckon with in resolution of the situation, and signalled its return to the world stage. Not only has Russia been able to fulfil its goals in the country, it has also used its success as a springboard to engage with various players in the region. These include building of bilateral relations with major regional players like Saudi Arabia, Israel, Iran, Turkey and Egypt.

IN the Libyan conflict, it has actively coordinated with Turkey, managing to become a key player in the negotiations between opposing sides. In the Middle East, Russia’s pragmatic foreign policy has been on full display, allowing it to engage on a transactional basis with other regional players. While it remains to be seen how this pans out in the long-term, it has helped Russia gain a foothold in the region.

These goals have been achieved both through skilful diplomacy, and optimum use of its military resources, which has greatly increased its standing in the region. The Russian moves have also benefited from an absence of a coherent, viable strategy from the US, a vacuum Moscow has been glad to fill, sensing an opportunity to enhance its presence at the expense of Washington.

In Africa, Russia has been driven by economic, political, and security goals, leading it to convene the first ever Russia-Africa summit in 2019. Given its fairly limited economic strength in the region, Russia has turned to the security domain (arms sales/training and consultancy/use of PMCs (Private Military Contractors) to push for enhancing its presence through ‘asymmetric’ means.

It has also been argued that the use of PMCs in Africa highlights the limited ‘hard power capabilities and appetite for risk’ of Russia in the region. Also, their use has been pragmatic—‘to save costs, avoid military conscript casualties, and for reasons of plausible deniability.’ Having lost its influence in the region almost completely after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Russian turn to Africa remains at a low level currently, and fruitful engagement remains limited to a few regional states. This has also meant that its adventurism in Madagascar to influence presidential elections ended in defeat of the candidates that Moscow had backed.

Russia’s geopolitical and geo-economic limitations are nowhere as evident as in Africa, where China, the US, EU, and Japan are established players with deep pockets, which severely curtails any grand plans in the region. While Russia has ambitions in Africa, given the recent nature of its forays in the region, it will be some time before the effectiveness of its engagement can be gauged, given the low priority it has been accorded in Russia’s strategic aims.

Russia’s ties with the EU, which touched a new low after the 2014 Ukrainian crisis, had been slowly fraying for some time over diverging values and NATO expansion. The steady decline in relations with the US has only made it further difficult to strike any balance in the relationship, as strict economic sanctions continue to be imposed on Russia, both by the US and EU. Other incidents, including use of Russian security services for targeted assassinations in European countries, alleged support to the European Far Right, and information campaigns have only added to the mistrust, doing Moscow no favours in what is already a difficult situation.

Internal stagnation, which makes Russia a less attractive player for other states, will continue to be the biggest roadblock in achievement of its foreign policy ambitions. However, Russian leadership is yet to implement the much-needed structural economic reforms

Such incidents have often created more problems for Russia as compared to their relative gains. But the key problems are more deep-rooted than the use of the tactics mentioned above. But the breakdown of ties with the EU in 2014 stemmed largely from the result of events in Ukraine and the downing of MH-17; it was a development that only added to other critical areas of divergence stemming from differing views on the future of the world order and its possible direction.

IN fact, it is the ongoing churn in the emergence of a new world order that has complicated matters further for Russian policy makers. Moscow is deeply cognizant of the complexity of the current international system, given that it has had to search and build an identity for itself amid this evolution. As the US-led liberal world order has come under stress, and China has experienced rapid growth to make it the leading contender to challenge the established power, the future contours of a new world order remain elusive.

Since 2014, as Russia has seen its relations with the West deteriorate, it has steadily built its relations with China, which has today become its closest partner. At the same time, Russia’s ties with other players in Asia-Pacific, a region that is slowly becoming the centre of global economics and politics, have not kept pace with that of China. As a result, Russia’s pivot to East has faced criticism for failing to build a truly multi-vector policy in the region, and for the need to strike a balance in its relations with the rising power.

This would include a clear up-gradation of relations with Japan, South Korea, India, and the ASEAN states, alongside regional multilateral mechanisms to build on its idea of a Eurasian integration framework. Meanwhile, as of now, despite the power differential, Russia and China have managed to navigate their relations pragmatically. For instance, they have built amicable relations in Central Asia, where Russia remains a key player, and the cooperation between EAEU and China’s Belt and Road Initiative is only expected to deepen the collaboration.

The trust at the highest level of leadership—between President Xi Jinping and President Putin—is often credited for ensuring the steady development of these ties. Russia remains a leading player in Central Asia, despite the increased Chinese economic presence, and the efforts by regional states to have a more diversified foreign policy.

Russia has also shown increasing willingness to engage with multilateral institutions like BRICS, SCO, RIC and ASEAN—apart from CIS and EAEU. This is being done with an aim to diversify its foreign policy, strengthen its relations with emerging powers, promote its own values and ideas about a future world order, and strengthen its global position. Given that Russia is no longer a superpower and recognises that in a world where multi-polarity has not yet been established, the importance of multilateral institutions for a middle power to push its agenda remains significant.

Despite the obvious advantages of the format, Russia will have to deal with challenges associated with competing agendas of member-states, the rising power of China, and the limited ability some of these multilateral institutions have in order to deal with a changing world order.

THE CHALLENGES AHEAD

There is no denying that Russia has come a long way from the decline of the 1990s, and has been successful in restoring its position as a power to be reckoned with in the 21st century. However, given that the world order continues to evolve, Russia’s future in that order also remains unclear. Recognising that it is not one of the two major powers in the world, Russia has resorted to a variety of means to expand its influence, and achieve its own national interests wherever the opportunity has presented itself.

In searching a place for itself in the current global scenario, Russia has benefited from an absence of ideology or the desire to promote its own model of governance. However, not all its tactics have been successful, with some of them back-firing and causing long-term complications for Russia. In order to preserve its interests in the prevailing scenario, Moscow needs a steady development of its multi-vector foreign policy. As Russia seeks to further its global influence, the key challenge remains that of domestic economic growth.

Internal stagnation, which makes Russia a less attractive player for other states, will continue to be the biggest roadblock in achievement of its foreign policy ambitions. However, Russian leadership is yet to implement the much-needed structural economic reforms to facilitate achievement of its stated foreign policy goals.

THIS has raised questions about Russia’s vision—both for its own development, and for a future world order. While it has pushed for establishment of a multi-polar world order, such a development remains far from being realised. As the COVID-19 pandemic increases chances of an intensification in bipolar US-China rivalry, Russia will find itself in a precarious situation—negotiating a dire economic situation at home, and an unstable global order abroad.

As President Putin faces one of the most critical challenges of his presidency—the COVID-19 pandemic—he will have to determine an effective way to advance foreign policy goals amid the crisis. This would entail balancing the strategic relationship with China, dealing with a growing bipolar rivalry, and its impact on foreign policies of other countries.

In searching a place for itself in the current global scenario, Russia has benefited from an absence of ideology or the desire to promote its own model of governance. However, not all its tactics have been successful, with some of them back-firing and causing long-term complications for Russia

As of now, it has been noted that Russia’s foreign policy is less about the world order, and more about its place in that order, a question that the Russian leadership is still seeking an answer for. Like other powers grappling with an international order in a flux, and seeking to expand their presence, Russia too continues to search for its distinct place in the world.

Nivedita Kapoor is Junior Fellow with ORF’s Strategic Studies Programme. She tracks Russian foreign and domestic policy — and Eurasian strategic affairs. Nivedita’s PhD thesis is titled ‘Russia’s Policy towards East Asia: The China Factor: 1996-2014.’

Recent Posts

Related Articles

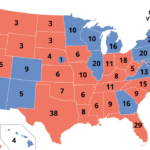

Globe ScanThe US Elections 2024: small number of voters in a few key states will decide the fate of Biden and Trump

Written by Gfiles Editor By Ashe N Ayers If you don’t know US...

ByGfiles EditorJuly 21, 2024Globe ScanFive billion passengers and earning is $6.14 per passenger claims Willie Walsh, Director General IATA

Written by Special Correspondent Willie Walsh Director General IATA presented a report at...

BySpecial CorrespondentJune 3, 2024Globe ScanIs Netanyahu, PM Israel, under pressure to resign?

Written by Gfiles Editor Iran’s unprecedented attack on Israel on April 14, in...

ByGfiles EditorMay 13, 2024Globe ScanPlaying with the minds of VOTERS

Written by Alam Srinivas IN 2014, Nix, a senior person in Cambridge Analytica,...

ByAlam SrinivasNovember 3, 2019 - Governance

- Governance