For decades, from the 1980s to 2000s, experts lamented that the burgeoning middle class, especially the youth, was completely apolitical and a party apathy towards governments, governance, and elections. Then, seemingly, things changed dramatically in the 2014 national election. The young, especially first-time voters, as also other sections of the middle class, both in urban and rural areas, amplified the Narendra Modi wave. Cutting across class, caste, and community, they excitedly and enthusiastically voted for the Bharatiya Janata Party, which shockingly won a majority on its own.

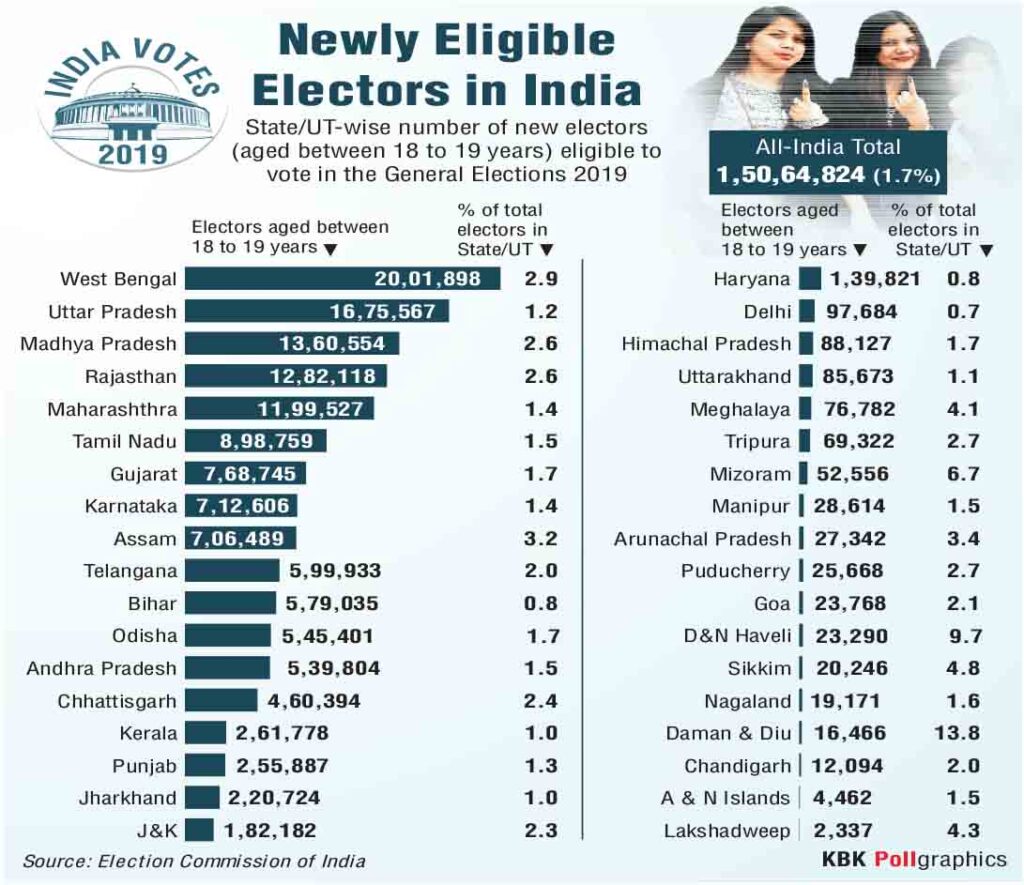

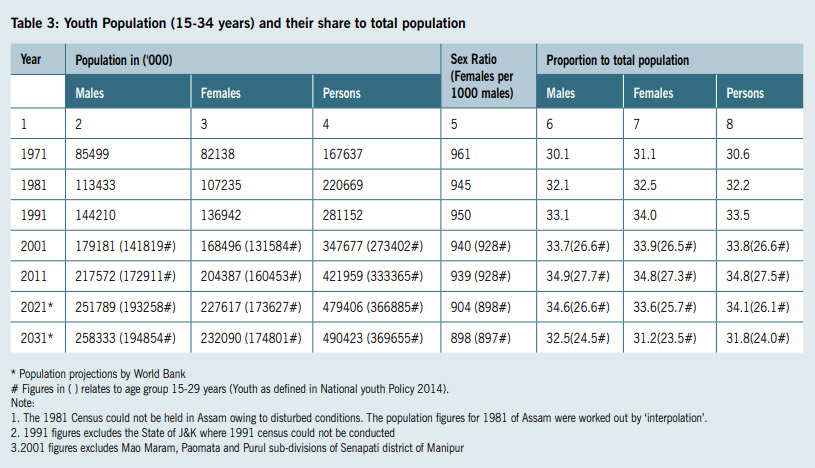

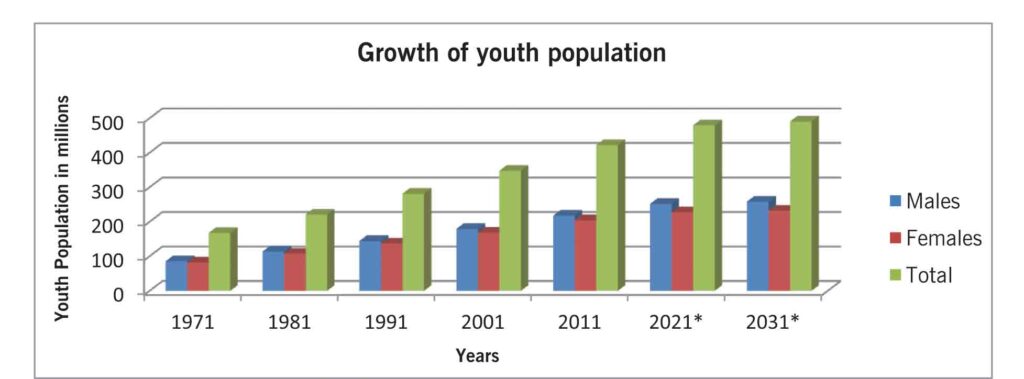

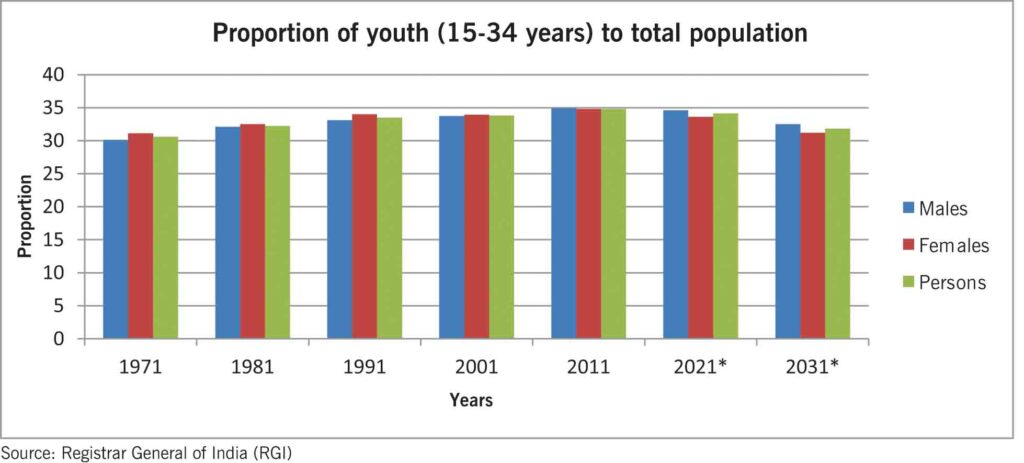

The statistics, which prove that the middle-class youth can influence any election today, are staggering. According to media reports, “81 million young voters will vote for the first time in the 2019 national elections, and could decisively influence electoral outcomes in 282 parliamentary constituencies”, i.e. in over 50 per cent of the Lok Sabha seats. Obviously, if we include those below 25 years, and older sections of the middle classes, the numbers are incredible. In every constituency, the youth can tilt the political balance. No wonder, the political parties are wooing these sets.

Such data and anecdotal evidence proves that India’s Millennials, or those born since 1980, are now politicised, enthusiastically participate in elections, and overtly support specific leaders and political parties. There is a paradox here since several surveys, including ones in the past few years, still indicate that Young India is apolitical, as it was since the 1980s.

A 2016 poll among those aged between 15 and 34 years showed that 46 per cent had no interest at all” in politics, and another 18 per cent had “little interest”. Although the remaining 36 per cent is huge, its impact on elections is limited.

How does one explain this contradiction? The first thing to do is to make nuanced distinctions between politics, ideology, electoral participation, and power games. Since the 1980s, when the late Rajiv Gandhi opened up the economy, in a restricted manner, from shackles of the Licence-Quota Raj, economics, in the form of new jobs and business opportunities, became an obsession with the middle class. This was accentuated in the 1990s, when Narasimha Rao-Manmohan Singh duo broke these chains. Economics, rather than politics, became a crucial rallying point for the young generation.

As the youth benefitted from the jobs in the sunrise sectors, like telecom, IT, manufacturing, and other services, it had little focus on governments and governance. Once these sectors were opened up, they grew in the 1990s despite what the policy makers did. The State wasn’t important for the middle class, which during the 1960s and 1970s had depended on the former’s benevolence in the form of opportunities in civil services and state-owned enterprises. Hence, politics was divorced from the lives of the younger generation because of the frenetic growth in the private sector.

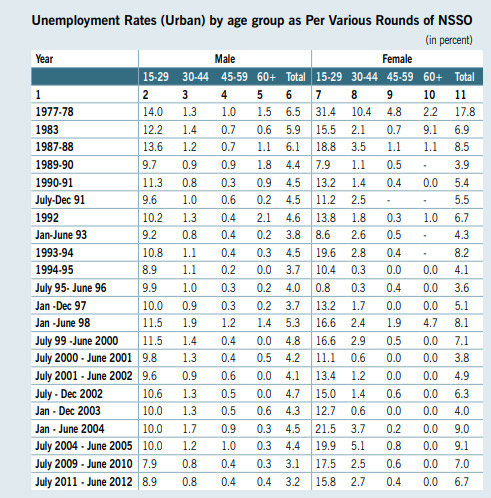

This changed in the 2000s. Despite high growth rates, sometimes in double digits, India was gripped by ‘jobless growth’. Even in the happening sectors like IT, the prospects dimmed. In the case of manufacturing, employment dipped due to several factors such as automation, cost-cutting, higher productivity and artificial intelligence. Simultaneously, the same happened in labour-intensive areas like construction and real estate. Suddenly, private sector was no longer a panacea for the middle class, especially given the spate of instant hiring and firing, which demoralised the youth.

Since the 1990s, the State was happy with the de-politicisation of the young, as it could easily sway poor and rural voters through freebies. In fact, the governments felt that since the middle class wasn’t voting, it was legitimate to withdraw some of its subsidies, like on petrol, diesel, and LPG, and force it to pay the higher market prices. At the same time, in a bid to keep the young away from elections, it doled out different kinds of benefits, like lower or zero taxation on certain incomes, and other forms of tax breaks. However, this fine balance too became lopsided in the 2000s for fiscal reasons, as the State was forced to reduce its budgetary deficits.

Suddenly, the youth was caught between the devil and the deep sea, or a rock and a hard place. At one extreme, its bonhomie with the private sector, minus the State, was decimated. At the other, the State withdrew, or reduced, its doles, and focussed on the poor. No jobs and no doles! The only choice with the middle class was to ask the government for help. Earlier, it didn’t need the State; now, this was paramount for its social and economic survival. Governments and governance became the new focal point.

HOWEVER, it will be wrong to assume that the youth became politicised, or got attracted to certain ideologies. The near-death of Communism in 1989, after the break-up of the Soviet Union, de-radicalised the youngsters. Hence, they moved from idealism, which was driven by both the notion of freedom and equality among the various sections. They also delinked themselves from the romantic notions of Socialism, which had bankrupted governments. Their dream-like experiences with Capitalism and Free Market, which helped them enormously in the 1990s, turned into nightmares in the 2000s.

What happened was that the middle-class looked-for ways to engage actively with governments, but only to seek benefits. It wanted the State to deliver what it sought more in terms of social and economic status, rather than political power. As one study pointed out that the middle class’ “actions are about protecting their own interests and social privileges”. The Indian experience still showed that there was no “direct correlation between higher economic development, education, middle class (and) higher political participation”, unlike in the more matured countries.

Since the middle class is not homogeneous, as is wrong assumed, but extremely complex heterogeneous entity, riddled with caste, class, and community complications, the various sections didn’t respond similarly. The New Middle Class, a prosperous section in cities, “engages with the State as a ‘client’” and “demands that the State ‘steer rather than do’” to guard its interests. This section wants “efficiency, merit, competition… over distributive justice, equity, and democracy, which it perceives as messy business of ‘dirty politics’”.

Although the middle class in the smaller cities and towns shared the overall aspirations of their counterparts in the larger ones, “their consumption pattern and location in the economy is not the same”. Nor is their engagement with governments because of the lack of proximity to the powers-that-be. The middle class from the “historically marginalised sections” still depend on the State for “rights and entitlements”. Thus, there was a bid to get something from the governments, but the rules of interactions were different.

Amidst this indifference for politics, and the desire, a need, to connect with governments, a new factor kicked in—Demographic Dividend. During the 1980s and 1990s, the youth and middle class invariably thought that they didn’t have the power, rather the numbers, to influence politics from the outside. They obviously didn’t wish to enter politics. So, they remained aloof, which was fine as long as their social and economic lives weren’t impacted by the governments, or their policies. As long as the State left them alone to pursue their objectives, they left the State alone.

The middle class looked for ways to engage actively with governments, but only to seek benefits. It wanted the State to deliver what it sought more in terms of social and economic status, rather than political power. As one study pointed out that the middle class’ “actions are about protecting their own interests and social privileges”

By the 2000s, the middle class, albeit in various ways given the extreme fragmentation among them, realised that the political arithmetic had swung in its favour. There was a growing feeling that even if they couldn’t combine as a single entity, given their differences, they could still put pressure on the political structures in the states. If over two-thirds of the population was under 35 years, and half the population was under 25, and there was a huge segment between 18-35 years, such voters could unbalance the old electoral equations based on castes, communities, and religions.

As India became Young India, and as experts began to talk about how the youth will help the country as a superpower in this century, the younger generation became confident, self-assured, and believed in its capacity to externally engage with politics to change the system. If certain sections voted according to pre-existing notions, the youth could emerge as the ‘swing factor’ to tip the scales in favour of specific politicians and political parties. Thus, it could sway politics without being an inherent part of it. It just had to enthusiastically participate in the elections.

Thus, elections became a new path to push the political structures to think of what they could do for the middle class. This process was enhanced by the mindset among the electoral regulators, Election Commission, and evolved politicians that unless the youth, possibly the largest voting section, did not participate in the electoral process, it will undermine democracy. Hence, they initiated efforts to convince the younger generation to join the electoral rolls as registered voters, and participate in the elections. This yielded fruits as the voter percentages went up over the past few years.

Given the fact that the middle class was still de-linked with political parties and ideology, it chose to electorally support charismatic leaders, who promised to deliver hope and change, growth and development, honesty and transparency in governance. This explains the spectacular rise of leaders such as Narendra Modi, Prime Minister, and Arvind Kejriwal, Delhi’s Chief Minister, in the recent past. The younger generation was loyal to the personalities, rather than the ideology that their party represented.

Coupled with the above processes was a strange, largely un-noticed and under-studied, phenomenon. Although the middle class was de-politicised, it somehow and interestingly continued to participate in ‘causes’ during the 1980s, 1990s, and early 2000s. In 1989, the youth backed VP Singh, who fought on the anti-corruption plank, to defeat Rajiv Gandhi in the national elections. The youngsters took to the streets, and set themselves on fire, to protest the quota regime and Mandal Commission. It attacked the construction of large dams, and mining activity.

Later, these transformed into protests against social causes “such as demand for ‘Justice for Jessica Lal, Justice for Priyadarshini Matto, and Nitish Kataria (case)’”, to the “anti-corruption protests in 2011 (Anna Hazare), and the anti-rape protests (Nirbhaya case) in 2012—these movements became more amorphous, drawing in the inspiration and some participation of urban working class”.

The Anna Hazare movement, which was captured by Kejriwal, as also others, became national ones with active participation of the youth in urban and rural areas. They forced the governments to act—and change.

At the same time, the middle class understood their abilities to influence the power structures, and the so-called system, through other means. For example, they were either cajoled or forced to enter various forms of institutions of power. According to a study, this happened in the form of their appropriations of civil society organisations, which exercised political power from a distance, “middle class neighbourhood organisations such as Advanced Locality Management groups or Resident Welfare Associations, or other parallel structures which are increasingly becoming part of the governance of cities—circumventing the formal democratic process”.

Although the middle class was de-politicised, it somehow and interestingly continued to participate in ‘causes’ during the 1980s, 1990s, and early 2000s. In 1989, the youth backed VP Singh, who fought on the anti-corruption plank, to defeat Rajiv Gandhi in the national elections. The youngsters took to the streets, and set themselves on fire, to protest the quota regime and Mandal Commission

With such experiences in political management, outside the purview of formal politics, gave the middle class the confidence that it could impact the electoral process. This could be done with becoming a part of the overall political process, although people from the middle class did join politics or become not-so-active members of political parties. The extensive role that it played, either as insider or outsider, was during the election process. It was thus that elections became a means to an end, a political means to social and economic ends that the middle class desired and revered.

This is how the Great Indian Middle Class, which is large yet fragmented in many ways, came to engage with politics, and influence it. All this happened even as it remained largely distanced itself from active politics, political parties, and ideology. Selfish interests dictated its decisions to influence governments and governance from outside. The de-politicised middle class became a crucial electoral influence, which forced the political parties to take heed.

Alam Srinivas is a business journalist with almost four decades of experience and has written for the Times of India, bbc.com, India Today, Outlook, and San Jose Mercury News. He has written Storms in the Sea Wind, IPL and Inside Story, Women of Vision (Nine Business Leaders in Conversation with Alam Srinivas),Cricket Czars: Two Men Who Changed the Gentleman's Game, The Indian Consumer: One Billion Myths, One Billion Realities . He can be reached at editor@gfilesindia.com