- Cover Story

- Governance

- Globe Scan

- Corruption

- State Scan

- Talk Time

- Cover Story

- Governance

- Globe Scan

- Corruption

- State Scan

- Talk Time

Recent Posts

© Copyright 2007 - 2023 Gfiles India. All rights reserved powered by Creative Web INC.Cover StoryDisrupted

WhatsApp, Google, and Facebook will definitely influence, may be even distort and manipulate, Indian Elections 2019. Here’s why no one—companies, policymakers and regulators—is seriously interested in curbing the electoral abuses and manipulations on social media

Alam SrinivasMarch 3, 201913 Mins read101 Views

Written by Alam Srinivas

Written by Alam SrinivasBUDDHIST texts have often referred to the analogy of a finger and the moon. Even the late Bruce Lee used it in a dialogue in his seminal Hollywood chart-buster, Enter The Dragon. In essence, it implies that when a wise man points his finger at the moon, the uninitiated or the fool looks at the finger. In the process, the latter may fail to notice the real nature of both the finger and moon. The reason: she “mistakes the pointing finger for the bright moon”.

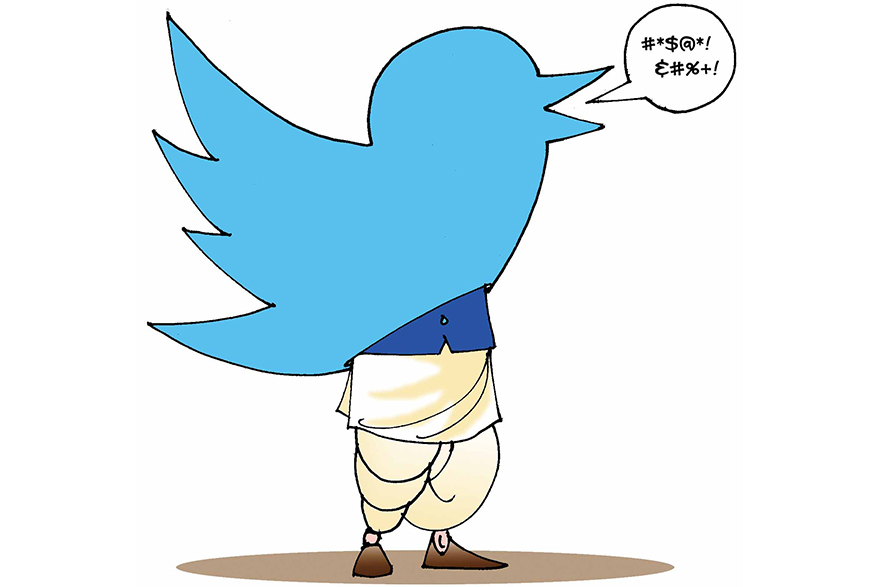

There is a modern version of the imagery. Now, when a finger points at the moon, the powerful and influential elite, which includes corporate giants and political leaders, forces the people to look at the finger. The former ensures that the citizens get warped up in small issues and forget the bigger picture. This is what the social media and tech giants such as Google, Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp and Instagram, along with the political parties, have done.

There is mounting and definitive evidence that social media is abused, distorted and manipulated by enemy nations, foreign intelligence agencies, hackers and cyber-criminals, and even genuine political parties to successfully influence electoral results across the globe. Over the past few years, it has happened in all the five populated regions—North America, South America, Europe, Asia, and Africa. The nations included the US, the UK, and France.

However, the tech giants invariably reacted post-facto—i.e. after the manipulation was proved—and never in a proactive manner. Policymakers and regulators focused on new laws, putting pressure on the companies to clean up their acts and make the process transparent. In the end, the actions and decisions minimally addressed the malaises. In effect, they missed the real issues. What was achieved was a kind of bamboozlement to dazzle the citizens.

For the tech giants, attracting more users and gathering more data is crucial to profitable business models. In addition, they need to encourage and enhance innovative ways to use and process the data to make it more useful for the other corporate users and advertisers. Any restrictions on data, or users, will impact the revenues and profits of the social media companies. Hence, they would be cagey, even adamant, to take steps to impose restrictions.

THE political parties and their supporters use the social media extensively. Facebook, WhatsApp, Twitter and Instagram are the new electoral tools. The former US President, Barack Obama, said that he used them just the way John F Kennedy used TV in 1960 to defeat Richard Nixon. Thus, the politicians, whether they belong to the ruling regimes or opposition, don’t wish to choke the platforms that can sharpen their election strategies.

Let us analyse the loopholes in the recent decisions that were announced, and promised, by the tech giants to make Indian Elections 2019 fairer and transparent. We will also focus on why they are so half-hearted.

There is mounting evidence that social media is abused, distorted and manipulated by enemy nations, foreign intelligence agencies, hackers and cyber-criminals, and even genuine political parties to successfully influence electoral results across the globe

Myth # 1: Online political ads pose the real problem

Recently, Facebook (FB) announced that it has made political advertising on its platform more transparent. Such ads will now carry a “paid by” and “published by” tags so that users can figure out the origins. Any advertiser will need to give more details to FB. The ads will be archived and the library will be publicly accessible. Since the payments for such ads came from dozens of countries during the 2014 Indian elections, it has mandated that the money can now only come from Indian bank accounts.

SO far, so good! However, the truth is that most of the abuses, especially during the past US presidential election, and the one in France, related to normal messaging. A report by the US-based Brookings Institution concluded that online election manipulations don’t often support a specific candidate or party. In contrast, they merely enhance and wedge the existing “social vulnerabilities”. The divisiveness in the different societies was merely amplified.

For example, in Europe, these issues related to “national sovereignty and immigration, Islam, terrorism, and the EU (European Union) as a globalist, elitist body”. In the US, “Russia’s disinformation machine has focused on racial tensions, criminal justice policy, immigration… and class divisions.” Online activists groups were created to spread hate. In her book, The Death of Truth, Michiko Kakutani said they formed competing groups for and against an issue to organise protests through online communities.

According to the various US intelligence reports, Russia-funded websites used their FB and twitter accounts and handles to highlight the various ‘Occupy Movements’, like the “Occupy Wall Street” one. This movement was “framed… as a fight against the ‘ruling class’ and described the current US political system as corrupt and dominated by corporations”. Even after the US presidential elections, when Donald Trump won, the Russia-supported online and social media sites “aired a documentary called ‘Cultures of Protest’ about active and often violent political resistance”.

This happened in Indian elections too. During the last assembly election in Uttar Pradesh (UP), social media was used to widen the chasm between communities. “People shared images of the former Chief Minister Akhilesh Yadav in a skull cap to project him as pro-Muslim and anti-Hindu. The image didn’t say this but the comments of those who shared them in WhatsApp group conveyed the anger,” claimed a professional who handled the advertising for several UP politicians during the elections.

A report by the US-based Brookings Institution concluded that online election manipulations don’t often support a specific candidate or party. In contrast, they merely enhance and wedge the existing “social vulnerabilities”. The divisiveness in the different societies was merely amplified

Prior to the UP assembly election, a letter, which was addressed to a District Collector, was shared. The writer said that he would hold a reading of the Ramcharitra Manas at his house and will ensure that no loudspeakers are used, and that the chant is only heard within his premises. “It went viral, and most comments related to how the Muslims were allowed to hold their prayers over loudspeakers in their mosques, but the Hindus had to give such assurances to the administrators in Akhilesh Yadav’s regime.

Similar divisive campaigns to further divide the society were carried by different political parties in different states. Except for the 2014 national election, which was partially driven by positivity—growth, development and employment—by the BJP, most of the other national and assembly elections in India in the recent past were stoked by societal, communities, and caste divisions. This was true in the other countries too.

Myth # 2: Fake accounts and BOTs are the real culprits

Social media giants contend that the problem lies with non-genuine accounts and non-existent users. Recently, FB claimed, “Using machine learning we’ve gotten more effective at either blocking, or quickly removing fake accounts. And that’s important since they are often the root of a lot of the bad activity that we see on our platform. And we have come to the point that we stop more than a million accounts per day at the point of creation.”

The same is true for BOTs, or human-curated fake accounts, which enable to amplify divisive messages. These artificial accounts, which can have genuine-sounding names of people from specific countries, create momentum that enables messages to reach out to ever-growing base of users. Online advertisers and marketers agree that they routinely face the blocking of BOT accounts by social media platforms. “Only today, 10 of my BOT accounts were blocked,” said one.

BUT fake accounts and BOTs are a part of the problem. Today, advertisers and political parties have honed their skills to form huge human chains through organic and inorganic tactics. They use real accounts, or accounts linked to real people who may never become the users of social media. Even BOTs can be linked to one’s maid or driver’s mobile phone to make them seem genuine. “This is what we do regularly, when spotted,” says an online marketer.

Ami Shah, a Bangalore-based academician with expertise in online and political marketing, explored how the online human chain works. She researched on the last assembly election in Maharashtra. According to her presentation, one of the national parties divided the state into 55 regions. Apart from the core social media team of six people, there was a content head in each region. Each of the 288 constituencies had 11 people each, which included one head and 10 party workers. In addition, there were 100 “content carriers” in each constituency.

THUS, a total of just over 32,000 people (6+55+3,168+28.800) were directly involved in the social media political messaging. The chosen platform was WhatsApp. However, this chain of real users became gigantic, when each of the 100 “content carriers” in each constituency was asked to send the messages to at least 100 contacts. This enhanced the reach nearer to three million. The number almost doubled when “each content carrier’s contact forwards to at least one contact”.

Myth # 3: Combating fake news holds the real key

All the tech giants now claim that they have taken effective steps to curb the proliferation of fake news. This is largely done through manual interventions, through partnerships with fact-checking agencies in dozens of countries monitored by small internal tams and automation. While the first effort is akin to finding a needle in a haystack, the second aims to reduce the size of the haystack. FB claims its motto is to “look for the needle and shrink the haystack”.

According to FB, automation “reduces the noise in the search environment which directly stops unsophisticated threats. And it also makes it easier for our manual investigators to corner the more sophisticated bad actors. In turn, those investigations keep turning up new behaviours, which fuel our automated detection and product innovation.” Ultimately, the goal is to “create this virtuous circle”.

However, as we mentioned earlier, political messaging has become suave and nuanced, and doesn’t even directly target the politicians. It either creates an environment of hate and divisiveness in the societies, or enhances it through regular messaging, which may be neither fake nor complete truth. Ami Shah noticed the increasing use of satire, through caricatures or comic strips, to achieve this objective.

During the last assembly election in Maharashtra, humour was extensively used to influence voters. The BJP, for example, launched two WhatsApp campaigns, Bhau Cha Dakka (Brother’s Push) and Aghadi Cha Ghotala (Scams by Former State Governments). The former was “devised around a fictional character, Rambhau, a man from middle-class family”. In conversations with his wife, Chandrika, and son, Bandya, the family’s hilarious conversations focused on common concerns and grievances in urban areas.

Shah maintains that “humour was given a different flavour based on the preferences of the voters in different regions” of the state. For example, the BJP found that people in Vidarbha preferred “harsh humour”, those in Marathwada “factual and direct humour”, and those in Konkan “witty humour”. Regular messages were crated and sent and shared through WhatsApp to influence voters.

While in this case the messaging wasn’t divisive or distorted, sarcasm can widen the chasms within a society. This was regularly confirmed in several other countries such as the US, the UK, and France. The trick is to figure out what is genuine and what is fake in direct messaging between users, and which messages divide the society. The norms established by the Election Commission of India for political speeches and physical campaigning should apply in such cases. And tech giants need to help.

Even in the cases of fake news, the social media platforms seem to be way behind the perpetrators. A tech company is normally ahead of the technology curve, or large companies like Google and FB buy out start-ups with innovations to stay abreast. But when it comes to fake news, they throw up their hands to claim that it is a tough nut to crack. The trick is not only to curb its dissemination, but also to punish the guilty.

Political messaging has become suave and nuanced, and doesn’t even directly target the politicians. It either creates an environment of hate and divisiveness in the societies, or enhances it through regular messaging, which may be neither fake nor complete truth

Most experts claim that while it may not be that easy to control the creation and distribution of fake content, the technology exists to pinpoint the person who first sent or shared the offensive audio, video, or text. But, of course, if this is done diligently and assiduously, it will disrupt the business models of the social media companies, and political strategies of all the parties. Hence, it is in their interests to only control, when found, and leave it at that.

Myth # 4: Social media companies have enough safeguards to protect the users’ data and their privacy

The tech giants consistently claim that they have protocols and mechanisms to protect the users’ data, even when it is shared with researchers, academicians, and advertisers and other companies. They propagate the falsehoods that they are safest platforms, which invest huge amounts every year to ensure the users’ privacy. In addition, they have initiated efforts to inform the users and media about the best ways to protect their data, and also spot fake news.

SADLY, time and again, various global studies and investigations concluded that this wasn’t the case. In fact, the tech giants were quite lethargic and lazy when it came to protect the users. In some cases, they may have colluded, either deliberately or knowingly, with the culprits, who misused the data of not only the specific users, but those of their friends and contacts as well.

In the case of the Cambridge Analytics scandal, when FB data was misused in the US elections, the UK’s Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), the country’s independent authority to uphold information rights in the public interest, indicted FB. It found that “Facebook did not take sufficientsteps to prevent apps from collecting data in contravention of dataprotection law”. This was a major reason for later breaches in data security and data misuse.

Similarly, in the particular scam, an initial genuine app “was able to obtain the data of Facebook users who used the app,” as well as the “data of the app user’s Facebook friends”. The data access was defined by privacy setting on the users’ “privacy settings” on FB. However, “unless it was specifically prevented by the app user, and the app user’s friend, the app was able to access the data of both persons by default”. If the users were unaware, the app could steal huge data.

The fact is that the tech giants actively encourage the use of the data they collect by researchers to innovate models that can help existing and potential advertisers. This is the business model of Google, Facebook, and others. In many cases, as the ICO found “close working relationship between Facebook and individual members of the research community”. There were “frequent meetings and travel at Facebook’s expense” between the two.

Once an app is developed, the social media companies are lazy to ask the researchers to delete the original data, as also delete any derivatives or models designed through them. This is important because academicians have claimed that by referring to “as few as 68 Facebook ‘likes’, they were able to predict with a high degree of accuracy a number of characteristics and traits, as well as other details such as ethnicity and political affiliation”.

In this manner, they can build psychographic profiles of the users, including their friends and contacts, and influence them through targeted messaging. More importantly, this works as an “echo chamber”, where the voices and messaging from the others, including competitors, are not heard. Before the elections, this emerges as a powerful tool for the political parties to sway the fencesitters. If the manipulators can access their profiles, the elections can be rigged to a large extent. It is the fence-sitters who decide the result of most elections in most nations.

YEARS ago, a US-based professor claimed that algorithms existed that could predict which FB user was going to shift cities or residence, and which one was a political fence-sitter. He demonstrated this by asking his students to present five posts each of users, possibly friends, and rightly predicted the political ideologies of those people, whom he didn’t know and who remained anonymous. This was what Cambridge Analytics did after accessing data illegally.

All this would still be not-too-dangerous if the users had the knowledge to understand how their data can be abused. The ICO found that this wasn’t so. First, they didn’t know how their data was used to profile them, and determine what they saw. Controls were available to the users, but they were “difficult to find” and “were not intuitive to the user”. While users were informed that their “data would be used for commercial advertising, it was not clear that political advertising would take place on the platform”.

Myth # 5: Controls on social media platforms are enough

Policy makers and regulators (Election Commission) feel that asking the social media players to fall in line to some extent will achieve the desired result to make elections more transparent. But as the rigging of the US elections by Russia shows, there is a concerted and multi-pronged strategy. Social media activity is just a part of it. Russian actors used mainstream media, social media, hacking and cyber crime to influence the past presidential election.

US intelligence agencies found that for years Russia financed the growth and expansion of a TV outlet, RT (formerly Russia Today), in the US and other countries. According to a declassified report, “RT states on its website that it can reach more than 550 million people worldwide and 85 million people in the United States; however, it does not publicise its actual US audience numbers.”

A tech company is normally ahead of the technology curve, or large companies like Google and FB buy out start-ups with innovations to stay abreast. But when it comes to fake news, they throw up their hands to claim that it is a tough nut to crack

Media companies like RT then use their websites and social media platforms to reach out to a larger set. For example, “since its inception in 2005, RT videos received more than 800 million views on YouTube (1 million views per day), which is the highest among (US) news outlets”. Russian hackers gain control of sensitive political content by accessing email accounts of politicians, as they did with the Democratic Party, and its candidate, Hillary Clinton.

Such emails, or political content is then released through known and mainstream channels like Wikileaks, which was indeed the case during the last US presidential campaign. According to the intelligence agencies, RT was in touch with Wikileaks, and announced that it was the “only Russian company” to partner with the latter. It added that it had “received access to ‘new leaks of sensitive information’”.

There are reasons why viewers in several countries get attracted to news outlets like RT. Experts believe that the “TV audience worldwide is losing trust in traditional TV broadcasts and stations, while the popularity of ‘alternative channels’ like RT or Al Jazeera grows. RT markets itself as an ‘alternative channel’ that is available via the Internet everywhere in the world, and it encourages social interaction and social networking”.

Hence, only a combined multi-faceted approach by tech giants, policy makers, and regulators can work to curb online malpractices in elections. Each one, and they together, have to look at the larger picture, the forests, rather get obsessed and drowned by the trees, which though are important enough. But for that to happen, the companies will need to be prepared to take a hit on revenues and profits, and political parties for a hit on their electoral chances. Obviously, neither will happen.

Recent Posts

Related Articles

Cover StoryTablighi Jamaat : 1000 years of revenge

Written by Vivek Mukherji and Sadia Rehman Two contradictions are evident. Through April...

ByVivek Mukherji and Sadia RehmanMay 5, 2020Cover StoryWINDS OF CHANGE

Written by Gopinath Menon ADVERTISING : The name itself conjures up exciting images....

ByGopinath MenonMarch 4, 2020Cover StoryTHE ECONOMIC ROULETTE WHEEL

Written by Alam Srinivas THE wheel spins, swings, and sweeps in a frenzied...

ByAlam SrinivasMarch 4, 2020Cover StorySYSTEMS FAILURE, SITUATION CRITICAL

Written by Vivek Mukherji ONE of most quoted allegories of incompetence for a...

ByVivek MukherjiMarch 4, 2020 - Governance

- Governance