- Cover Story

- Governance

- Globe Scan

- Corruption

- State Scan

- Talk Time

- Cover Story

- Governance

- Globe Scan

- Corruption

- State Scan

- Talk Time

Recent Posts

© Copyright 2007 - 2023 Gfiles India. All rights reserved powered by Creative Web INC.Governancee-retailers flouting law

While foreigners can invest in the B2B segment of the chain, they cannot enter the B2C one. Clearly, e-retailers, who have attracted FDI, cannot sell directly to the final consumers

Ali RiazApril 4, 20159 Mins read77 Views

Written by Ali Riaz

Written by Ali RiazAMAZON, the US online retail giant, has admitted that there are huge question marks over its Indian operations. In a recent filing with the American stock market regulator, Securities and Exchange Commission, it said that its activities in India could flout existing or future laws, or their interpretations, by government officials. The business “could be subject to fines and other financial penalties, have licenses revoked, or be forced to shut down entirely”.

Such a confession lends credence to the charges against e-retailers, present in India that they operate in the grey areas of the existing laws. The major allegation against them is that they publicly and openly act in a manner that is against the letter and spirit of the FDI (foreign direct investment) norms. In fact, the tax authorities and Enforcement Directorate (ED) have initiated action against Amazon, Flipkart and Snapdeal.

As per law, FDI is partially allowed in e-retail. While foreigners can invest in the B2B segment of the chain, they cannot enter the B2C one. Clearly, e-retailers, who have attracted FDI, cannot sell directly to the final consumers. They can only operate in that part of the distribution chain which is akin to the wholesale part of the brick-and-mortar retail. Foreign online retailers can trade in bulk orders, but cannot sell individual products to the retail customer.

Under the April 2014 guidelines, 100 per cent FDI is permitted in e-commerce, but subject to certain restrictions. The rules read: “E-commerce activities refer to the activity of buying and selling by a company through the e-commerce platform. Such companies would engage only in Business to Business (B2B) e-commerce and not in retail trading, inter alia, implying that existing restrictions on FDI in domestic trading would be applicable to e-commerce as well.”

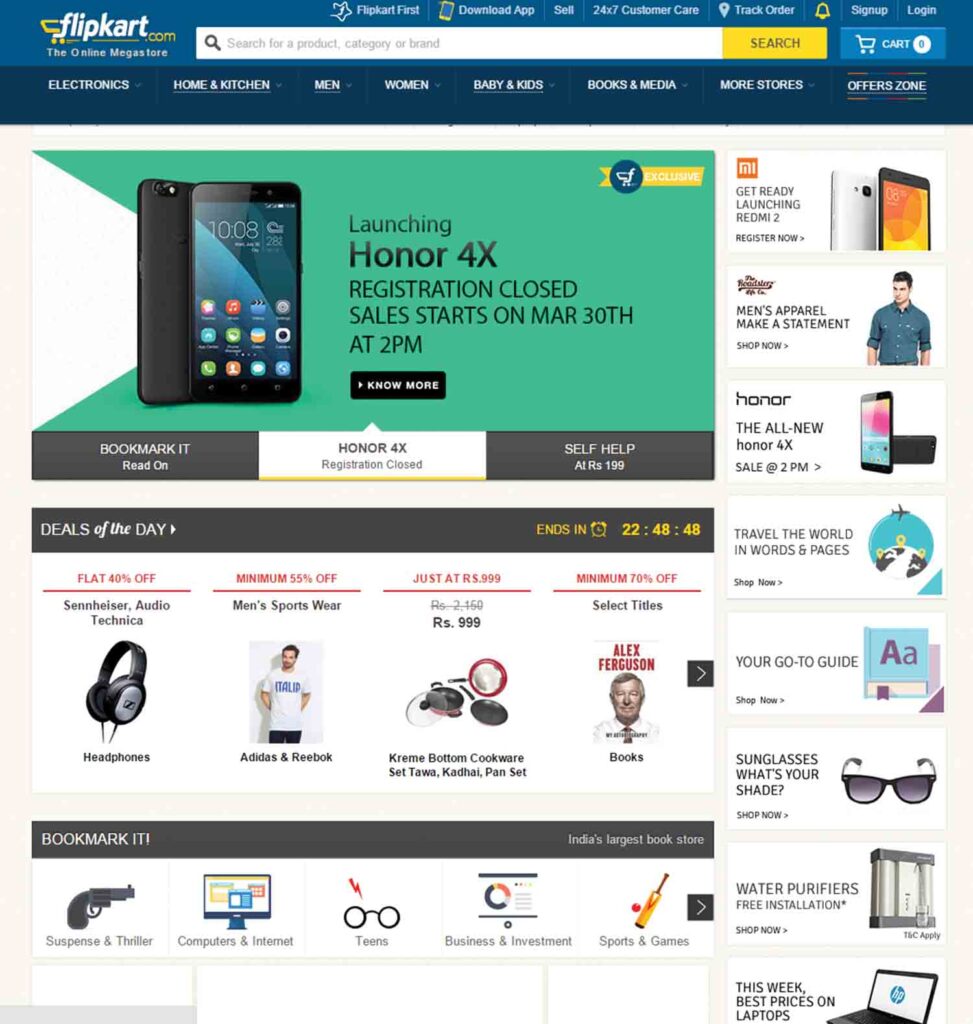

However, there is no denying the fact that Amazon, Flipkart and Snapdeal sell to retail customers. Most of the consumers order products on the online platforms, receive them through couriers in a packed condition, and pay cash on delivery of the items. When they have complaints, or wish to return the purchased items within 30 days, they connect with the 24×7 toll-free numbers. They can also track their orders on the e-platforms.

Another truth is that foreigners have invested huge amounts in e-commerce players in the country. Recently, Amazon announced it wishes to pump in $2 billion over the next few years in www.amazon.in. Last year, Flipkart received over a billion dollars from global investors. Recently, Chinese online retailer Alibaba’s attempt to snap up Snapdeal fell through. The deal to buy a small stake was estimated at $500-700 million, and valued Snapdeal at $4-5 billion.

How do these companies zig-zag around the curbs on FDI in B2C e-commerce? What are the issues red-flagged by the Indian investigating agencies against several online retailers?

Business models

Globally, e-retailers follow two operational models. The first is the marketplace model, where the online platform neither stores products at its warehouses nor maintains an inventory. It merely brings the buyer and seller together, and facilitates the deal. The second is the inventory model, where the e-retailer maintains an inventory and owns warehouses. Amazon pursues both these models and even manages hybrid ones that combine both.In India, the foreign e-retailers and those who have attracted FDI insist that they follow the marketplace model. They are, therefore, in the B2B space and bring the buyers and sellers together. They claim that they manage and run websites that provide online marketplaces to aid the transactions. The sellers place the orders online, but the inventory of the products is maintained by the buyers, who advertise their items on the websites, and supply them offline.

A recent Price Water house Coopers-Assocham study on the evolution of e-commerce in India said, “Most e-retailers have started practicing the marketplace business model with suppliers storing on their behalf and delivering as per the requirement and thus falling under the B2B category.” This is the reason, contend the retailers, why they incur huge losses.

The operations of the e-retailers are akin to what happened in the brick-and mortar retail sector. At a time when FDI was only allowed in back-end organised retail, and not in front-end, the US-based Walmart exploited loopholes in the law

Information on www.trak.in shows the extent of the huge losses of the three top e-retailers in India—Flipkart, Amazon, and Snapdeal—in 2013-14. Flipkart earned revenues of Rs. 179 crore against a loss of Rs. 400 crore, Amazon Rs. 169 crore against Rs. 321 crore, and Snapdeal Rs. 154 crore against Rs. 265 crore. To put it in perspective, the loss-to-sales ratio for the three companies was 2.23, 1.90 and 1.72, respectively. Revenues in these cases are not the total of the prices of the products sold, but a fraction that is shared by the buyers. They also include the listing fees that buyers pay the retailers to advertise their products on the online platforms.

Loopholes galore

However, Amazon publicly admits that it is more than an online platform. Its website says that it provides “certain marketing tools and logistics services to third-party sellers to enable them to sell online and deliver to customers”. The retailer believes that these activities comply with Indian laws. But, recently, it said that these business structures may “involve unique risks” and may be considered by law enforcement agencies to be skirting the laws.THE logistics of e-retail comprise three critical processes—Pick, Pack and Ship. Since people order 1-2 products, millions of items need to be individually picked from the various warehouses, whether owned by the sellers or e-retailers. Each product has to be packed and the packing depends on the item ordered. Finally, it has to be shipped efficiently and quickly, since most online retailers offer delivery within 24 hours for most of the products.

Logically, one can assume that if the e-retailer directly participates in any or all of the three processes, it becomes a part of the overall distribution chain. Hence, in such cases it can be construed that it operates in the B2C segment and not in the B2B one, or as a marketplace facilitator. In India, there are several ways in which this happens. The most important is in shipping, or the last-mile delivery. The final courier-based delivery is critical to woo customers.

As the PwC study said, “Logistics in developing economies such as India may act as the biggest barrier to the growth of the e-commerce industry. Till date, logistics models developed in India target the metropolitan and the tier-I cities where there is a mix of affluent and middle classes and the Internet penetration is adequate. In India, about 90 per cent of the goods are being ordered online and are moved by air, which increases the delivery costs for the e-retailers.”

Indian e-retailers, who were earlier “dependent on third-party delivery firms”, changed their strategy. Issues specific to e-retailing, such as the “problems associated with fake addresses, cash-on-delivery, and higher expected return rates have made e-retailers consider setting up their captive intensive logistics businesses,” said the report. However, this has pushed up costs; captive models are 10-20 per cent more expensive than outsourced parties.

“Facing difficulties… it (Flipkart) has started its own logistics arm named e-Kart. E-Kart provides a robust back-end support… and ensures timely deliveries. To achieve economies of scale, recently e-Kart started providing back-end support to other e-retailers,” said the PwC report. It added that Amazon India has set up a logistics arm named Amazon Logistics and started offering same-day delivery. Aren’t these violations of the FDI rules in B2C?

There is no denying the fact that Amazon, Flipkart and Snapdeal sell to retail customers. Most of the consumers order products on the online platforms, receive them through couriers in a packed condition, and pay cash on delivery of the items

E-shenanigans

Investigating agencies contend that e-retailers find novel ways to e-manipulate—and openly flout—the existing laws. For example, until 2013, Flipkart owned several warehouses even as it received foreign investment. This was barred under the FDI guidelines. This was an open secret. The PwC study mentioned that the company “started with a consignment model where goods were procured on demand and turned into inventory e-retailer supported by registered suppliers….”IT added that “Flipkart established warehouses in Delhi, Bangalore, Mumbai and Kolkata, managing a fine balance between inventory and cost of delivery goods”. It was only after the ED initiated action against the firm and issued a showcause notice that the warehouses were either closed or sold to other firms. However, the new ownership of the warehouses is not clear and ED officials allege Flipkart exerts ‘significant influence’ over their management.

One of the reasons that the ED doesn’t believe Flipkart’s assertions is that until recently the latter owned WS Retail, which acted as the front-end of the retail chain and interacted directly with the customers. However, to skirt around the FDI rules, the group company that received foreign investment was its B2B arm, Flipkart Online Services, which managed the online platform. This was an ownership structure created to fool the law enforcement agencies.

Another grey area in the business is the role played by, what the e-retailers dub, the distribution centres and fulfilment centres. Amazon has several of the latter in the metros and others claim to manage distribution centres. A few experts feel that these centres act as part-warehouses and part-inventory management tools. Although they don’t pro-actively stock products, these are the places where items are bunched together before being couriered to the buyers.

The centres act as regional and local hubs for the last-mile distribution in a specific geography. For example, the distribution centre in Delhi may cater to consumers in Delhi, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh. The fulfilment centres also act as after-sales service points to ensure customer satisfaction. Therefore, they fulfil the core of marketing activities in modern jargon—customer happiness.

Commissions & omissions

The size of the e-retail business in the country is estimated at $6 billion in 2015. It is expected to grow at a compounded annual growth rate of 40-50 per cent until 2020. Of all the products sold online, electronics comprise 34 per cent, apparel and accessories 30 per cent, books 15 per cent, and beauty and personal care 10 per cent. Despite the decent size of the market, how come Amazon and Flipkart earn meagre annual revenues of Rs. 169 crore and Rs. 179 crore, respectively? Both the figures are less than $30 million each!As mentioned earlier, what the e-retailers show in their books are not the gross values of the sold merchandise, but only the commissions that they receive from the sellers. These entries are meant to convince the lawmakers that they don’t operate in the B2C segments, but receive fees to facilitate deals between buyers and sellers. However, the income tax department feels that in such cases, the e-retailers act as ‘commission agents’ and form a part of the distribution chain.

Tax officials in Karnataka have put more spanners in the wheels of e-commerce. They allege that the e-retailers’ distribution and fulfilment centres actually act as warehouses and storehouses. They feel that most e-retailers store thousands of products at these centres even before they have received orders from the customers. In fact, experts contend that three-fourths of Amazon’s annual sales come from pre-stored or inventoried items.

Amazon publicly admits that it is more than an online platform. Its website says that it provides “certain marketing tools and logistics services to third party sellers to enable them to sell online and deliver to customers”

When senior managers of e-retailers talk to the media and at seminars, they boast that their logistics systems, coupled with advanced software, can predict future sale of most products. This gives them the flexibility to anticipate the movement of products which, in turn, enables faster delivery of the goods. This logistics system and management help them pick, pack, ship and reach most customers within 24 hours without making any mistakes.

If what e-retailers themselves admit, and tax officials, contentions are correct, one can technically and legally say that the former do maintain warehouses. In such cases, say the taxmen, it is the online retailers which have to pay value-added tax (VAT) on the products. At present, to prove that they are just trade facilitators, the e-retailers use their distribution and fulfilment centres for the last-mile connectivity, receive cash on deliveries, keep their commissions and pass on the remaining amounts to the various sellers, who end up paying VAT.

INCOME tax officials in Karnataka contend that the e-retailers should pay VAT. They have asked over 100 suppliers to stop providing goods to Amazon, which has a fulfilment centre in the state. The state is thinking of changes in the local laws—VAT is a state subject—to include e-commerce in the VAT ambit. E-retailers maintain that they shouldn’t pay VAT.

The operations of the e-retailers are akin to what happened in the brick-and-mortar retail sector. At a time when FDI was only allowed in back-end organised retail, and not in front-end (physical retailers with FDI couldn’t open retail stores), the US-based Walmart exploited loopholes in the law. While it handled the wholesale procurement to the Bharti Group, which managed the stores, it was Walmart that took all the decisions related to the stores, including inventory, products’ placement of, look and feel of the shops, and even hiring of people.

Clearly, e-retailers have acted against both the letter and spirit of the FDI guidelines. It is high time the government takes concrete action against their Indian operations, and provides clarity in the existing laws. The consumers wish to know whether FDI is allowed or banned in e-B2C.

Recent Posts

Related Articles

GovernanceNewsBackdoor entry of Private players in Railway Production Units ?

Written by K. SUBRAMANIAN To Shri G C Murmu C&AG Dear Shri Murmu,...

ByK. SUBRAMANIANFebruary 22, 2024GovernanceNailing Labour to The Cross

Written by Vivek Mukherji THEY grease the wheels of India’s economy with their...

ByVivek MukherjiMay 5, 2020GovernanceBig Metal Momentum

Written by GS Sood PRECIOUS metals especially gold and silver are likely to...

ByGS SoodMay 5, 2020GovernanceStrengthening Social Enterprise Ecosystem: Need for systemic support from the Government

Written by Jyotsna Sitling and Bibhu Mishra THE world faces several challenges today....

ByJyotsna Sitling and Bibhu MishraMay 5, 2020 - Governance

- Governance