- Cover Story

- Governance

- Globe Scan

- Corruption

- State Scan

- Talk Time

- Cover Story

- Governance

- Globe Scan

- Corruption

- State Scan

- Talk Time

Recent Posts

© Copyright 2007 - 2023 Gfiles India. All rights reserved powered by Creative Web INC.GovernanceHamster on a wheel

The demand to ban TikTok and break the encryption technology of WhatsApp highlights the challenges that rapidly evolving digital technologies pose for India. The absence of data protection laws further exacerbates the problem, leaving millions of Indians vulnerable to behavioural manipulation by vested groups. Vivek Mukherji reports.

Vivek MukherjiAugust 8, 20197 Mins read118 Views

Written by Vivek Mukherji

Written by Vivek MukherjiNext time you log into Facebook and click on that thumb sign to like a post or write a comment or update your status or undertake one of those silly surveys that pop up on your timeline, pause for a moment and think. You might not realise but you have voluntarily provided some more byte-sized information about yourself to some big data analytics firm in another part of the world that will be fitted into the mosaic of similar data about yourself gathered over a period of time by bots powered by Artificial Intelligence residing in the vast expanse of cyberspace to build a detailed psychographic profile of you. This is called metadata.

Then one fine day, Facebook ads or political messages of a certain persuasion start appearing on your timeline; rest assured, it’s not at all random. In fact, you have been targeted for that type of messaging. The more you consume a particular type of message, more you will be bombarded with similar genre of information. Like a hamster on a wheel that can’t get off, you will be providing a constant feedback loop that will keep getting bigger until you succumb to the persuasion to take action that has been shaped by the constant din of a particular genre of messages that have been appearing on your timeline over a period of time. In military parlance, it’s called psyops.

You may not be in any warzone, but you are a digital pawn in the battle of digital giants. Big tech companies that own social media platforms or develop apps will utilise your data—in other words a part of you— to rake in big money without your explicit consent. In the process, they might even succeed in tweaking or altering your behaviour towards a cause, issue or a product. This is the holy grail of consumer behaviour—a marketing maven’s or a political strategist’s wet dream.

If you believe all this is a piece of fiction or your writer’s imagination, then log of Netflix and invest 1 hr 54 minutes to watch the recently released documentary, The Great Hack. It delves deep into the investigations carried out by journalist Carole Cadwalladr for The Guardian into the dark dealings of the notorious big data analysis firm, Cambridge Analytica (CA). The now defunct company used Facebook data to manipulate voters’ sentiments in the run-up to the 2016 US elections and Brexit referendum.

During the period CA worked on the Trump campaign, it managed to gather 5,000 data points on every American voter to bombard them with customised digital ads at an individual level. A large chunk of the ads promoting Facebook pages with racist and biased political messages, explicitly aimed at driving a wedge in the society and thereby manipulating the voter’s behaviour, were set up by Russian intelligence.

The critically acclaimed documentary raises wide-ranging and chilling questions regarding data privacy issues. Who is the rightful owner of your data? You or the companies that own these social media platforms and apps?

But the most critical question pertains to the cornerstone of any democracy: Can a hostile power interfere with the free and fair electoral process of a country? Or, can a political party use these platforms to manipulate voter sentiments or instigate trouble with sharply targeted messaging aimed at a particular section of the public? In Europe some of these contentious issues have been addressed after the General Data Protection Right (GDPR) came into effect in May 2018. It imposes substantial financial penalty on tech companies for data breaches or parting with data without the express consent of the users.

Closer home, in India, the debate on personal data protection and privacy remains fuzzy at best. Two instances that have been in the news in recent days elucidate the consternation among the various peer groups lobbying to tilt the discourse one way or the other. In the first instance, Swadeshi JagaranManch (SJM), an affiliate of the RSS, has written to the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) urging the government to ban the video-making app TikTok on the grounds that it violates privacy and has a corrupting influence on its users. In the second case, two Public Interest Litigations (PIL) have been filed in the Madras High Court, praying for traceability of WhatsApp messages. According to the tech monitoring website Medianama, the PILs further pleaded to “declare the linking of Aadhaar or any one of the Government authorised identity proof(s) as mandatory for the purpose of authentication while obtaining any email or user account.”

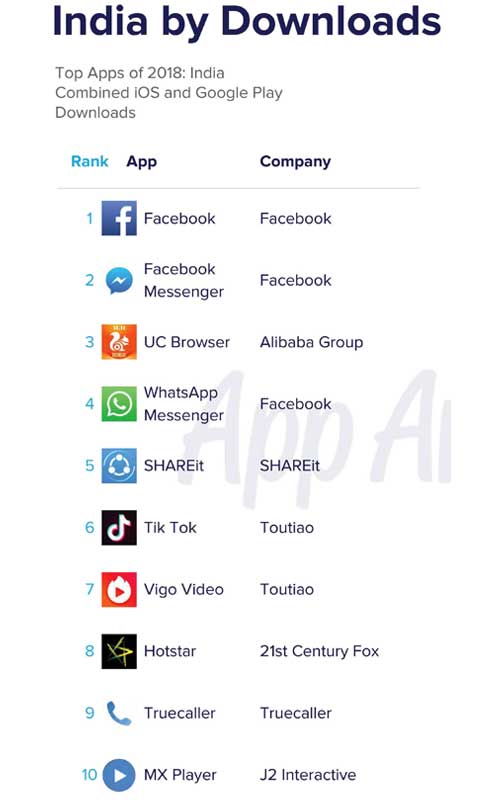

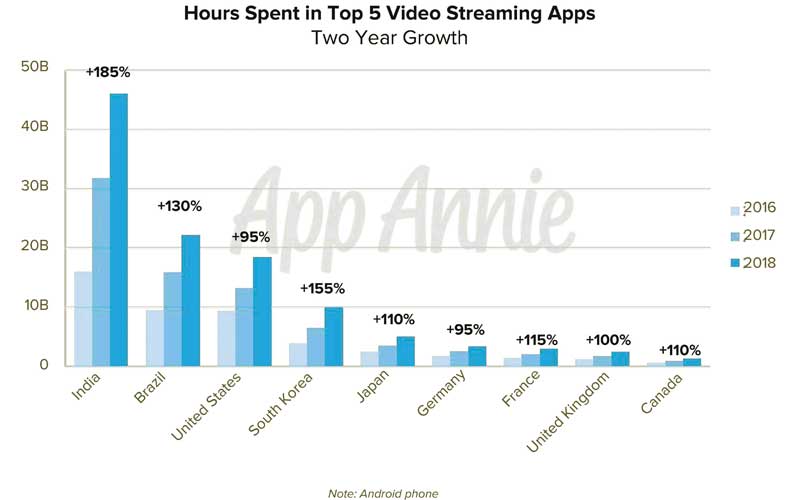

The contradiction in the two stands is self evident. TikTok is a video-making app that’s owned by Chinese tech company ByteDance. It allows its users to make 15-second videos and upload it on its website. The app is immensely popular in India in the age group of 16-24. According to App Annie, a mobile technology monitoring agency, it was the sixth most downloaded app in India in 2018. The app comes with a rich bank of pre-loaded filters, music and other features that enable the users to make a wide variety of fun videos and upload them on their timeline. SJM, however, wants it banned in India on the grounds that the app seeks permission to access contacts stored in the phonebook, enable location feature of the device and that it promotes pornography.

In the ongoing case in the Madras High Court against WhatsApp (owned by Facebook), the petitioners want the tech company to break its encryption technology to allow state agencies to intercept any message sent by its users and group chats in the interest of curbing fake news that spreads very rapidly through this most popular messaging service. India is the largest market for WhatsApp with a user base of almost 400 million and is ranked No.1 in App Annie’s estimation of monthly active users in 2018.

The counsel for WhatsApp in turn informed the court that breaking its encryption technology will not only entail changing its global software architecture, it will jeopardise the lives of many of its users like journalists and activists, who use the messaging service to communicate with their sources. Experts have also pointed out that as WhatsApp is an American company, it will be a violation of the First Amendment that guarantees freedom of speech, in case it is forced to break its encryption technology.

The absence of a coherent privacy policy and low-level of cyber awareness among the people, including policy makers, are responsible for the tardiness in addressing issues that are constantly evolving due to the galloping pace of technology development. One of India’s leading infosec experts, who works on sensitive government projects, told gfiles on condition of anonymity that the default position of various governments in India has been a “strong urge to intrude into people’s lives.”

He points to Section 69 of the Information Technology Act to drive home his argument. The sweeping scope of the section gives state agencies enormous discretionary powers to intercept computer-based communication. “Where the Central Government or a State Government or any of its officers specially authorised by the Central Government or the State Government, as the case may be, in this behalf may, if satisfied that it is necessary or expedient to do in the interest of the sovereignty or integrity of India, defence of India, security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States or public order or for preventing incitement to the commission of any cognizable offence relating to above or for investigation of any offence, it may, subject to the provisions of sub-section (2), for reasons to be recorded in writing, by order, direct any agency of the appropriate Government to intercept, monitor or decrypt or cause to be intercepted or monitored or decrypted any information generated, transmitted, received or stored in any computer resource,” reads the section.

“When you look closely at the section and break it down in lay terms, it seems it had been drafted on the presumption that every Indian who uses a computer is a potential enemy of the state. It’s a highly regressive and draconian line of thinking in the 21st century,” says the expert.

When asked about the demand to ban TikTok in India because it allegedly violates privacy, the expert pointed that that banning an app is no solution. “It’s a very dangerous territory. Today it’s Tiktok, tomorrow it will be some other app or website. Is that the job of the government? There are far more pressing cyber security issues that need our attention and have to be addressed. It seems TikTok has enraged some people of a certain political ideology because youngsters have used it to lampoon our politicians,” he says.

Pressed for the best course of action to combat the exponentially growing menace of fake news in India, he points to the Finnish example. “Since 2014, Finland has been conducting courses for youngsters for identifying and reporting fake news. Now schools have made such courses as part of their curriculum. I feel that it’s the most sensible approach to tackle this problem. India might have improved its literacy rate, but in the real sense it’s a poorly educated country. On one hand, India is one of the fastest growing smartphone markets in the world, on the other people have such poor cyber awareness that it makes them prime targets for behavioural manipulation by vested interests,” says the expert.

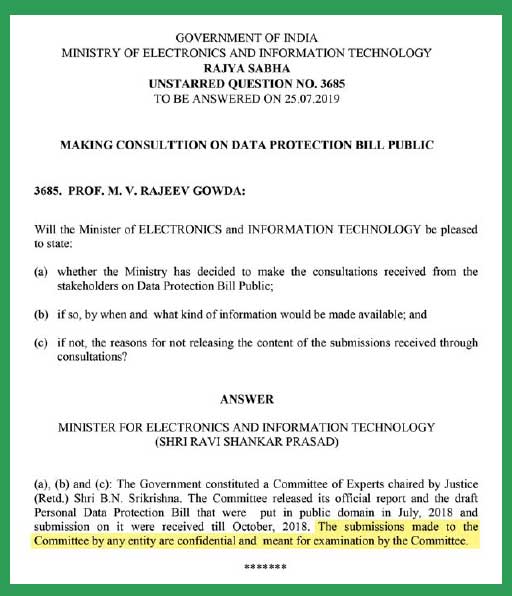

It seems India is finally waking up to the need to have personal data protection laws. In July 2018, the Shrikrishna Committee submitted the final draft of the Personal Data Protection Bill to the government after public consultation. The proposed bill draws a lot of ideas from Europe’s GDPR, but has faced criticism from digital rights activists and various other stakeholders for the government’s refusal to make the consultations public.

On July 25, Rajya Sabha member Prof. Rajeev Gowda asked if Ravi Shankar Prasad, Minister of Electronics and Information Technology, intended to place the inputs the committee received during consultation in the public domain. In response, the minister informed the upper house that the inputs were confidential and therefore, can’t be revealed. “The Government constituted a Committee of Experts chaired by Justice (Retd.) Shri B.N. Srikrishna. The Committee released its official report and the draft Personal Data Protection Bill that were put in the public domain in July 2018 and submission on it were received till October 2018. The submissions made to the Committee by any entity are confidential and meant for examination by the Committee,” said Prasad. The bill is yet to be tabled in Parliament.

With the Supreme Court ruling that privacy of individuals is a fundamental right in the Aadhaar case, it’s time to for India to bring in a sensible privacy protection law that is not draconian and is able to address the emerging challenges as technology continues to evolve at a blinding pace.

Recent Posts

Related Articles

GovernanceNewsBackdoor entry of Private players in Railway Production Units ?

Written by K. SUBRAMANIAN To Shri G C Murmu C&AG Dear Shri Murmu,...

ByK. SUBRAMANIANFebruary 22, 2024GovernanceNailing Labour to The Cross

Written by Vivek Mukherji THEY grease the wheels of India’s economy with their...

ByVivek MukherjiMay 5, 2020GovernanceBig Metal Momentum

Written by GS Sood PRECIOUS metals especially gold and silver are likely to...

ByGS SoodMay 5, 2020GovernanceStrengthening Social Enterprise Ecosystem: Need for systemic support from the Government

Written by Jyotsna Sitling and Bibhu Mishra THE world faces several challenges today....

ByJyotsna Sitling and Bibhu MishraMay 5, 2020 - Governance

- Governance