- Cover Story

- Governance

- Globe Scan

- Corruption

- State Scan

- Talk Time

- Cover Story

- Governance

- Globe Scan

- Corruption

- State Scan

- Talk Time

Recent Posts

© Copyright 2007 - 2023 Gfiles India. All rights reserved powered by Creative Web INC. Written by Janardan Thakur

Written by Janardan Thakur Janardan Thakur started his career in journalism with the nationalist Patna daily, The Searchlight, in December 1959. In his long and distinguished career spanning the reign of each Prime Minister since Independence, Thakur reported from the thick of some of the most momentous contemporary events at home and afar—JP’s ‘total revolution’, the Emergency, the bristling emergence of Sanjay Gandhi, the fall and rise of Indira Gandhi and then the rise and fall of Rajiv, the Kremlin of Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and Khomeini’s revolution in Iran, Ronald Reagan’s re-election in an America swinging Right, VP Singh’s ascent as a messiah with tainted magic and the rasping run to power of the BJP. Thakur’s journalism, from the very start, broke traditional moulds of reportage and writing, going beyond the story that meets the eye and into processes and personalities that made them happen. His stories on the Bihar famine of the mid-1960s and the manmade floods that ravaged the State were a sensation. He was perhaps alone in predicting defeat for Indira Gandhi in 1977 and again singular in exposing the corroded innards of the Janata Government that followed. A Jefferson Fellow at the East-West Center, Hawaii, in 1971, Thakur moved to New Delhi as a Special Correspondent for the Ananda Bazar Patrika group of publications in 1976. He went freelance in 1980 and turned syndicated columnist. In 1989-91, he was Editor of the fortnightly Onlooker, and The Free Press Journal. Thakur authored All The Prime Minister’s Men, probably the most successful of the crop of books that followed the Emergency. His All the Janata Men, the story of the men who destroyed the first non-Congress government in New Delhi, was equally successful.

Janardan Thakur started his career in journalism with the nationalist Patna daily, The Searchlight, in December 1959. In his long and distinguished career spanning the reign of each Prime Minister since Independence, Thakur reported from the thick of some of the most momentous contemporary events at home and afar—JP’s ‘total revolution’, the Emergency, the bristling emergence of Sanjay Gandhi, the fall and rise of Indira Gandhi and then the rise and fall of Rajiv, the Kremlin of Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and Khomeini’s revolution in Iran, Ronald Reagan’s re-election in an America swinging Right, VP Singh’s ascent as a messiah with tainted magic and the rasping run to power of the BJP. Thakur’s journalism, from the very start, broke traditional moulds of reportage and writing, going beyond the story that meets the eye and into processes and personalities that made them happen. His stories on the Bihar famine of the mid-1960s and the manmade floods that ravaged the State were a sensation. He was perhaps alone in predicting defeat for Indira Gandhi in 1977 and again singular in exposing the corroded innards of the Janata Government that followed. A Jefferson Fellow at the East-West Center, Hawaii, in 1971, Thakur moved to New Delhi as a Special Correspondent for the Ananda Bazar Patrika group of publications in 1976. He went freelance in 1980 and turned syndicated columnist. In 1989-91, he was Editor of the fortnightly Onlooker, and The Free Press Journal. Thakur authored All The Prime Minister’s Men, probably the most successful of the crop of books that followed the Emergency. His All the Janata Men, the story of the men who destroyed the first non-Congress government in New Delhi, was equally successful.

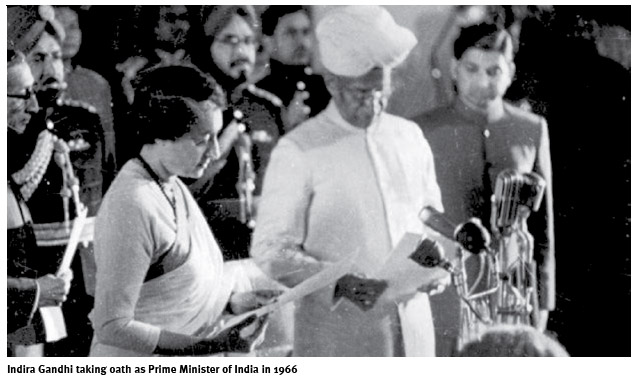

He passed away on July 12, 1999.PRIME Minister Indira Gandhi had started with hesitant steps. She had a ‘kitchen cabinet’, composed largely of the earlier members of the ‘Back-benchers’ Club’, who advised a low-key approach. For a time she retained LK Jha as her Principal Secretary. She had respect for his ability, but a major point against him was that he had been ‘too close to Shastri’. Even so, she was not for any drastic changes around her.

For a time, Indira just followed the path chalked out by her advisers and went along with the new economic policies initiated in the days of Lal Bahadur Shastri. She had travelled to the US some months after becoming the Prime Minister. On a bright windy morning in March 1966, she had landed in Washington, DC to a red-carpet welcome by President Johnson and his wife, Lady Bird, who had an armful of roses for Mrs Gandhi. Everywhere she went she was smothered in roses. In her speeches, Indira Gandhi had carefully avoided any criticism of the Vietnam war, which was raging at that time.

Serious talks on economic aid she had left to Asoka Mehta, whom she had appointed her Planning Minister. By May, it became clear that American aid would be forthcoming only after India acted on her promise to devalue the rupee. The government went ahead with the negotiations with the International Monetary Fund on the exact parity value of the rupee, which was changed relative to the dollar from Rs 4.75 to Rs 7.50.

Devaluation brought about the first polarisation in the Congress, and led to her initial break with Kamaraj, who had been opposed to the new-look economic policy which the devaluation epitomised. There were stiff protests from senior members of the Cabinet as well. They doubted whether devaluation could bring any substantial benefit to India. Kamaraj was especially incensed. How could his protege have taken such a major step without taking him into confidence? He insisted that the Congress Working Committee or the Parliamentary Board would have to discuss it before any official decision could be taken. Just a day before the devaluation was supposed to take place, LK Jha cabled the Indian Ambassador in Washington, BK Nehru, advising him to withhold any announcement, because there could be a change in policy.

Even so, the devaluation was announced on June 6, 1966, by the then Finance Minister, Sachin Chaudhuri, and within ten days the United States announced resumption of economic aid to India. The message was clear: Indira Gandhi had devalued the rupee under American pressure to get more aid.

The growing antipathies in the party and the negative impact of the rupee devaluation led to the fiasco of 1967, a year that proved to be another watershed in the country’s political history. On the eve of the elections that year, the country’s top industrialists mounted a fierce attack on economic policies and planning. The country’s difficulties, charged JRD Tata, were because of the “wrong priorities and inaccessible targets which have led to target missing”. Ghanshyam Das Birla was even more virulent in his attack. He blamed the dismal economic situation on the “kind of stupid plan that is prepared in this country by amateurs without knowing what is planning. They are still talking in terms of socialism about which they themselves do not know what they are talking about.” Birla predicted that the “Congress will come back to power, at least in the Centre, but with a highly reduced majority.” He was almost prophetic.

The Congress was stunned by the election results. The party’s majority in the Lok Sabha was reduced to 25, the lowest until then, and, what was worse, the Congress failed to win legislative majorities in eight important states: Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Rajasthan, Bihar, West Bengal, Orissa, Kerala and Madras. Candidates of Opposition parties had wrested from the Congress 264 seats in the legislative assemblies. Many interpreted the elections as the demise of the Congress monolith. The ‘end of an era’, it was called.

The Congress was stunned by the election results. The party’s majority in the Lok Sabha was reduced to 25, the lowest until then, and, what was worse, the Congress failed to win legislative majorities in eight important states: Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Rajasthan, Bihar, West Bengal, Orissa, Kerala and Madras. Candidates of Opposition parties had wrested from the Congress 264 seats in the legislative assemblies. Many interpreted the elections as the demise of the Congress monolith. The ‘end of an era’, it was called.FOR Indira Gandhi, it had been a rough campaign. A brickbat had hit her on the nose during her campaign in Orissa. She had arrived in Patna next day with a bandaged nose. She had insisted on keeping to her schedule despite her broken nose.

“Ever since plastic surgery was heard of, I have been wanting to get something done to my nose,” she wrote to her American friend, Dorothy Normal, an author and photographer, with whom she corresponded for long years: “I even started putting by money for it and I thought the only way it could be done without the usual hoo-ha was first to have some slight accident which would enable me to have it put right — as you know, things never happen the way one wants them to. You must have heard that at my meeting in Bhubaneshwar there was some pebble throwing. There were just a few students who had grouped themselves in a circle, standing, jumping, and shouting slogans…I gave my full speech, about forty to forty-five minutes, but while I was speaking I knew they must be throwing stones or something because the Press people who were below the dais looked alarmed and moved behind the dais…I got a large piece of brick right on my face. There was a spurt of blood — I thought at first that my nose was broken. Someone gave me a handkerchief…In Raj Bhawan I found that I looked like a boxer — I was a terrible sight in the mirror. My nose, the left side, looked completely crooked. I tried to put it right myself and heard a little ‘tik’ sound. The left lip had swollen to the size of a big egg…”

THE broken nose apart, she had suffered an electoral defeat which shook her up. Her credibility as an effective national leader was severely damaged. Some party veterans thought this was the best time to seize the opportunity to cut her to size. When Mrs Gandhi set out to form a new government after the general elections, her adversaries thought this was the time to set the cat among the pigeons: get Morarji Desai to mess up her kitchen. They started talking about a ‘working relationship’ between the two rivals. Morarji who had fancied himself as the ‘natural heir’ to Jawaharlal Nehru, would accept nothing less than No. 2 position, with the Home portfolio. She eventually agreed to give him Finance, with the additional title of Deputy Prime Minister. Desai promptly assumed the dominant role in the formulation of economic policies. DG Gadgil replaced Asoka Mehta as the deputy chairman of the reconstituted Planning Commission.

Suddenly, the menace of defections started. The Devi Lals, Bansi Lals and Charan Singhs and so many others of their ilk took the centrestage in various states. It was the beginning of the Samyukta Vidhayak Dal politics in the northern and eastern states. With it started chronic political instability, disregard for parliamentary norms and the gross abuse of Constitutional powers by governors, at the behest of an increasingly demoralised and manipulative Central government. Even the fears of national disintegration revived.

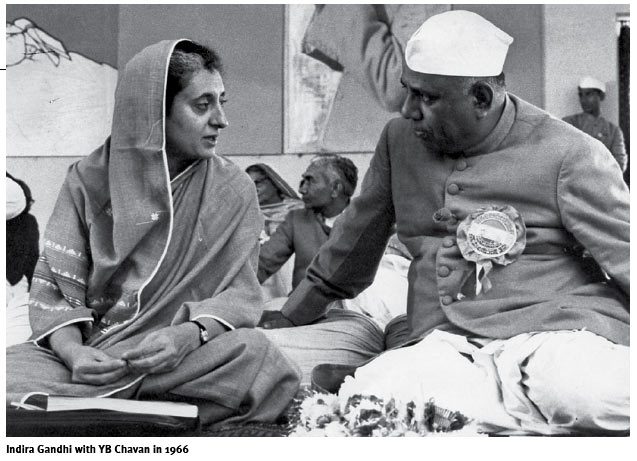

Indira Gandhi with YB Chavan in 1966 One of the best accounts of how the post-1967 coalition politics functioned is by the American political scientist, Paul R Brass: “After the formation of each government, it became known that a prominent individual belonging to a faction in the Congress or in a non-Congress party was disaffected with the government because he was not satisfied with his place in the government or was not given a position in it. The disaffected leader then began to gather supporters, while criticising the government in general terms for corruption or for failure to implement portions of the programme rapidly enough. Finally a prominent public event occurred or an issue was found which provided the leader with an immediate cause for defection with his loyal supporters. The defecting leader was then given the opportunity to form a government, which was either a non-Congress coalition or a minority government with Congress support. In either event, the defecting leader became the new Chief Minister, most of those who defected with him received ministerial office and a new crisis began. In the interim between the two governments the opposing forces in the legislature continually bargained for the support of independents and potential party defectors. The game came to an end when the governors became convinced that no stable coalitions were possible and that the Assembly should be dissolved and new elections should be called.”

In hindsight, Paul Brass was depicting only a rather civilised version of what coalition politics was to become in later years.

The politics of defection gained momentum. Between March 1967 and March 1970, as many as 1,827 legislators (the total number of seats in all the assemblies then being 3,487) had defected, some of them several times. In the same period, 23 governments came and went in the seven states of West Bengal, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, Madhya Pradesh, Punjab and Kerala. Legislators jumping onto the speaker’s rostrum or grappling with one another on the floor of various assemblies became the order of the day.

Indira Gandhi was by now caught up in a bitter battle for dominance in the affairs of the Congress Party and the government. Ranged against her were the old party bosses, while she on her side had a younger group of socialist radicals determined to wrest control of the party.

This was a time of deep introspection for Indira Gandhi. She adopted a new political style and made new adjustments to get in tune with the mood of the people. She packed off LK Jha to the Reserve Bank as Governor and took on PN Haksar, who was to change the whole tone and tenor of the Prime Minister’s Office. Alumnus of the London School of Economics, Haksar had been attached to the Communist Party for some time and had practised law at Allahabad under Sir Tej Bahadur Sapru, during which time he had caught the eye of Prime Minister Nehru, who promptly picked him for the Indian Foreign Service.

In 1967 began the ‘Haksar years’ which saw the rise of Indira Gandhi and her virtual deification as Goddess Durga. One of the first things she did under Haksar’s advice was to disband her ‘kitchen cabinet’ and acquire a new team with a totally different outlook and expertise. It was Haksar who set her on the battle track, which led to the famous Congress split at Bangalore.

In June 1967, she took a pronounced pro-Arab position on the Egypt-Israeli war. This was the beginning of an active non-alignment, a tilt away from the first year’s bias towards America.

Hemmed in by Morarji Desai, Indira tried to maintain a balance in the cabinet by cultivating the support of trusted personal advisers like Dinesh Singh, whom she had made Foreign Minister. When she condoned attacks on the Syndicate members, party President Nijalingappa threatened disciplinary action against the radicals. When one of Indira’s supporters, ‘Young Turk’ Chandra Shekhar questioned the personal integrity of Morarji Desai on the floor of the Lok Sabha, the Parliamentary party authorised her to censure him, but she did not. Animosities between her group and the Syndicate grew. Patil and others began alleging that Mrs Gandhi’s Principal Secretary, known to be a leftist in his views, was acting as a conduit between the Soviet Union and the Prime Minister. There were charges that Indira Gandhi was out to “sell India to the Russians,” and in an interview Desai almost said as much.

By mid-1968, the Syndicate bosses, and now the term included K Kamaraj, were convinced that the only way was to get rid of the lady. Initially, Congress President Nijalingappa was reluctant, but he too was soon drawn into the Syndicate net.

They planned their first attack for the Faridabad session of the AICC in April 1969. Attempts to paper over the cracks failed; indeed, they only widened. For the first time, Mrs Gandhi took a clear position in favour of the radicals who had come together under the banner of Congress Forum for Socialist Action. There was no meeting ground on the economic and political issues, but the final break was put off for ‘a better opportunity’.

THAT opportunity came within a week of the Faridabad session. President Zakir Hussain died on May 3, 1969, and thus arose a chance for a proper trial of strength. To begin with, neither side was enthusiastic about the Vice-President VV Giri becoming the President. A final decision was left for a meeting of the Congress Parliamentary Board which was to coincide with the special session of the AICC at Bangalore in July 1969.

Initially, Mrs Gandhi did not object to the candidacy of Neelam Sanjeeva Reddy, who was then the Speaker of the Lok Sabha. But soon after he was officially nominated by the party, Mrs Gandhi came to know from some of her trusted lieutenants that Reddy’s candidature was part of a bigger conspiracy against her. “Once he becomes the President, Reddy will sack you and instal Morarji Desai as the Prime Minister,” they told her.

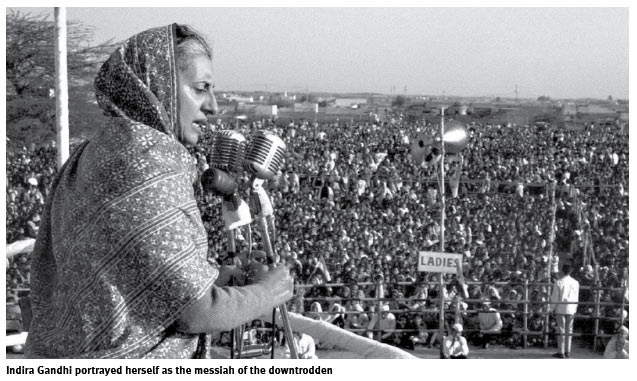

Matters came to a head at the Bangalore session of the AICC. Ideology, or rather the rhetoric of ideology, was Indira’s most effective weapon against her opponents. Her major weapon against her rivals was to put them in the category of reactionaries and conservatives, while she herself emerged as the one who favoured change, supported the interests of the poor and the oppressed.

Indira Gandhi portrayed herself as the messiah of the downtrodden It was before and after Bangalore that she honed her skills. The old fuddy-duddies of the Congress had realised that Indira was not the dumb doll they had thought she was when they put her in the Prime Minister’s chair. Not at all the ‘pliable consensus’ Prime Minister they had wanted. She had become imperious, and belligerent. She had gone to the Bangalore session of the All India Congress Committee armed with “just some stray thoughts rather hurriedly dictated”. The Working Committee almost ‘ignored’ the “stray thoughts” by just accepting them unanimously. Morarji Desai had introduced the “Resolution on Economic Policy and Programme” in the session and affirmed that he supported the Prime Minister’s ‘Note’ without any reservation. The Syndicate was more worried about what would happen at the Congress Parliamentary Board meeting. The old bosses expected to win a majority on the candidature of Reddy for the Presidential election. Just before the meeting was to begin, Indira Gandhi said that she was going to support Jagjivan Ram instead of Reddy. At the meeting, Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed, whom she later made the President, introduced Ram’s name, but Indira was defeated in a vote: four in favour of Reddy and two against. Morarji, YB Chavan, SK Patil and Kamaraj had voted for Sanjeeva Reddy, while Ahmed and Indira Gandhi had gone for Ram. Chairman of the meeting, Nijalingappa, and Jagjivan Ram had abstained from the vote.

HAVING suffered a blow, Indira devised a full-blast counter-attack. In a lightning move she divested Morarji Desai of the Finance portfolio, knowing that after this he would himself resign as Deputy Prime Minister. And then in another sudden move, she announced that 14 of the largest commercial banks in the country had been nationalised by a Presidential order.

She had sent a brief letter of dismissal to Morarji Desai, saying: “As a disciplined soldier of the party you lent support to the resolution which was adopted, even though I know that in regard to some of the basic issues that arise, you entertain strong reservations and have your own views about the direction as well as the pace of change. You have expressed your views clearly in the Working Committee and on other occasions. I have given deep thought to this matter and feel that in all fairness, I should not burden you with this responsibility in your capacity as Finance Minister, but should take it directly upon myself.”

The bottom line was: Indira Gandhi was henceforth to be the sole embodiment of the new economic policies, the sole messiah of the poor and the downtrodden.

Excerpted from Prime Ministers: Nehru to Vajpayee by Janardan Thakur, Eeshwar Prakashan, New Delhi

Recent Posts

Related Articles

Book ExtractThere’s Seven For You, Three For Me

Written by Ajay Mankotia My book There’s Seven For You, Three For Me–Chronicles...

ByAjay MankotiaFebruary 5, 2020Book ExtractThe Makings of Dalit Political Power

Written by Raja Sekhar Vundru AMBEDKAR hailed from a family of military men....

ByRaja Sekhar VundruJanuary 7, 2020Book ExtractThe Future of China-India Relations

Written by Dr Liu Zongyi Dr Liu Zongyi is a Senior Fellow at...

ByDr Liu ZongyiOctober 4, 2019Book ExtractThe Pied Piper of BJP

Written by Kumkum Chaddha A senior Congress leader, also an ex-chief minister, had...

ByKumkum ChaddhaMay 7, 2019 - Governance

- Governance

Janardan Thakur started his career in journalism with the nationalist Patna daily, The Searchlight, in December 1959. In his long and distinguished career spanning the reign of each Prime Minister since Independence, Thakur reported from the thick of some of the most momentous contemporary events at home and afar—JP’s ‘total revolution’, the Emergency, the bristling emergence of Sanjay Gandhi, the fall and rise of Indira Gandhi and then the rise and fall of Rajiv, the Kremlin of Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and Khomeini’s revolution in Iran, Ronald Reagan’s re-election in an America swinging Right, VP Singh’s ascent as a messiah with tainted magic and the rasping run to power of the BJP. Thakur’s journalism, from the very start, broke traditional moulds of reportage and writing, going beyond the story that meets the eye and into processes and personalities that made them happen. His stories on the Bihar famine of the mid-1960s and the manmade floods that ravaged the State were a sensation. He was perhaps alone in predicting defeat for Indira Gandhi in 1977 and again singular in exposing the corroded innards of the Janata Government that followed. A Jefferson Fellow at the East-West Center, Hawaii, in 1971, Thakur moved to New Delhi as a Special Correspondent for the Ananda Bazar Patrika group of publications in 1976. He went freelance in 1980 and turned syndicated columnist. In 1989-91, he was Editor of the fortnightly Onlooker, and The Free Press Journal. Thakur authored All The Prime Minister’s Men, probably the most successful of the crop of books that followed the Emergency. His All the Janata Men, the story of the men who destroyed the first non-Congress government in New Delhi, was equally successful.

Janardan Thakur started his career in journalism with the nationalist Patna daily, The Searchlight, in December 1959. In his long and distinguished career spanning the reign of each Prime Minister since Independence, Thakur reported from the thick of some of the most momentous contemporary events at home and afar—JP’s ‘total revolution’, the Emergency, the bristling emergence of Sanjay Gandhi, the fall and rise of Indira Gandhi and then the rise and fall of Rajiv, the Kremlin of Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and Khomeini’s revolution in Iran, Ronald Reagan’s re-election in an America swinging Right, VP Singh’s ascent as a messiah with tainted magic and the rasping run to power of the BJP. Thakur’s journalism, from the very start, broke traditional moulds of reportage and writing, going beyond the story that meets the eye and into processes and personalities that made them happen. His stories on the Bihar famine of the mid-1960s and the manmade floods that ravaged the State were a sensation. He was perhaps alone in predicting defeat for Indira Gandhi in 1977 and again singular in exposing the corroded innards of the Janata Government that followed. A Jefferson Fellow at the East-West Center, Hawaii, in 1971, Thakur moved to New Delhi as a Special Correspondent for the Ananda Bazar Patrika group of publications in 1976. He went freelance in 1980 and turned syndicated columnist. In 1989-91, he was Editor of the fortnightly Onlooker, and The Free Press Journal. Thakur authored All The Prime Minister’s Men, probably the most successful of the crop of books that followed the Emergency. His All the Janata Men, the story of the men who destroyed the first non-Congress government in New Delhi, was equally successful. The Congress was stunned by the election results. The party’s majority in the Lok Sabha was reduced to 25, the lowest until then, and, what was worse, the Congress failed to win legislative majorities in eight important states: Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Rajasthan, Bihar, West Bengal, Orissa, Kerala and Madras. Candidates of Opposition parties had wrested from the Congress 264 seats in the legislative assemblies. Many interpreted the elections as the demise of the Congress monolith. The ‘end of an era’, it was called.

The Congress was stunned by the election results. The party’s majority in the Lok Sabha was reduced to 25, the lowest until then, and, what was worse, the Congress failed to win legislative majorities in eight important states: Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Rajasthan, Bihar, West Bengal, Orissa, Kerala and Madras. Candidates of Opposition parties had wrested from the Congress 264 seats in the legislative assemblies. Many interpreted the elections as the demise of the Congress monolith. The ‘end of an era’, it was called.