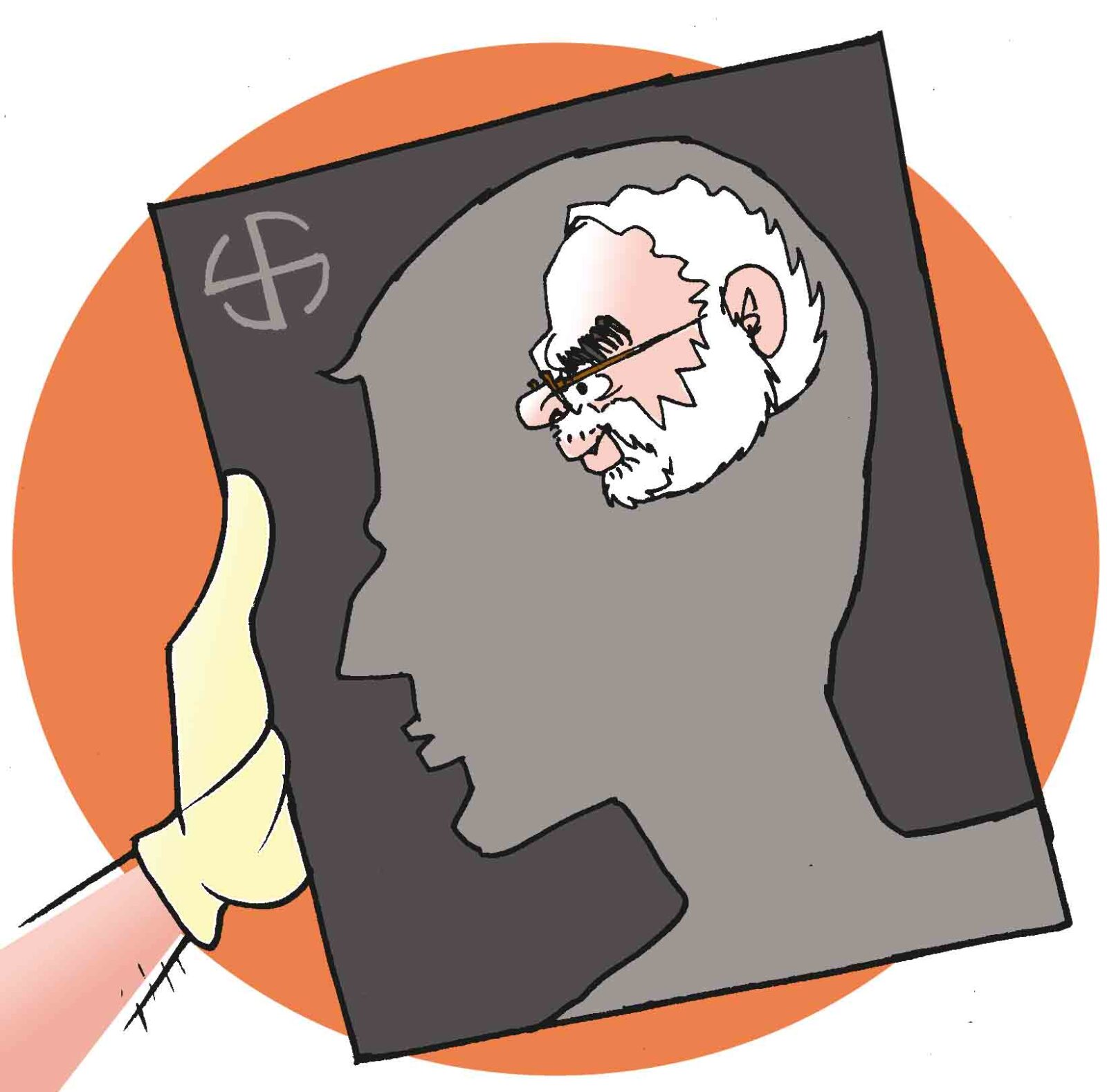

LIKE many of my compatriots, I have seen and judged Narendra Modi from widely different perspectives. There was a time when I saw him as a mass murderer who had engineered or, at the very least, permitted the anti-Muslim riots. He was portrayed by some as a lackey of the Adanis and the Ambanis, ready to oblige them going out of the way, and then travelling in executive jets for his election campaign at their expense. He was labelled as a dictator who treated his ministers with contempt and was an incipient Hitler.

Today many of us have a revised version in our hearts. The new Modi is a person risen from a less affluent background, who forsook the pleasures of family life and spent decades as a Vivekananda-style parivrajak and an RSS pracharak. A man driven by a passionate vision of his beloved country, which he wants to establish as the jagatguru of the world as in days of yore, a workaholic who slogs day and night without fatigue, a Prime Minister who is bubbling with ideas on how to improve the quality of life of billions of Indians and a leader who interprets Hindutva not in the parochial sense of anti-minorityism but the efflorescence of a perennial philosophy that gave tolerance and equidistance from all faiths to the Vedic rishis and made India the broad hearted land, giving shelter to the oppressed of all nations.

How has Modi wrought this miracle? I think the magic began when Mani Shankar Aiyar lampooned him as a chaiwala during the election campaign. Another person might have taken offence or hit back at the Stephenian arrogance of this nose-in-the-air ex-diplomat. Modi playfully launched a chai chaupal across the country and invited his countrymen to enjoy a cup of tea at his expense and gossip about this and that with him. He has since used the chaiwala tag frequently to define his humble origins and made political capital of his ability to raise himself to the highest post of the country!

He got transformed in many hearts when he called Nawaz Sharif’s bluff and cancelled the talks at the foreign secretary level because Pakistan tried to be oversmart and asked its High Commissioner to go ahead with his tea party for the Hurriyat leaders. We warmed to Modi when he ordered the paramilitary forces to give a befitting reply to the indiscriminate shelling by Pakistan. All of a sudden, India’s Kashmir policy, Pakistan policy and Muslim policy acquired new definitions.

Modi has already fired first salvoes of the new dispensation. His prime confidant, Amit Shah, has declared that the strategy this time is to form a BJP-led coalition in J&K. Many observers feel that he will be able to do so. Even the unprecedented floods are working to the BJP’s advantage, as the flurry of activity by the central forces is contrasted with the somnolence of the local administration. This would represent a tectonic shift and effectively counter the pro-Muslim bias that has infused the State government policy ever since the State acceded to India in 1948.

Compare and contrast the Vajpayee-led NDA government which tried to start a conference of the Central Advisory Board of Education with “Vande Mataram!” and faced a walkout by education ministers of Congress-ruled States, with Modi who ended his Independence Day speech with “Vande Mataram!”, thus forcing children of all faiths to repeat this slogan without recourse to any overt melodrama.

Modi’s Muslim policy is not yet clearly enunciated. Yet one can discern an emerging pattern. He seems to be moving inexorably towards the Australian model. Two Australian Prime Ministers have made national broadcasts on TV, asking the Muslims to behave or leave. They had not invited the Muslims to come and settle down in Australia. The Muslims had come of their own volition and so they would have to follow Australian laws like the rest. Their children would have to attend government schools and sing the prayers laid down for all students.

Indian Muslims have not had anyone talking to them with similar frankness. On the contrary, they have been treated with kid gloves and treated like a votebank. They are permitted to have their maktabs and madrassas, which breed youth proficient in mindless intoning of scriptural texts, but ignorant of modern languages, science and mathematics.

For the present, the strategy seems to be to unleash the extreme right of Hindutva and permit low-grade communal skirmishes, with mild reproofs being administered by the lower echelons of the BJP hierarchy. If the lessons are not learnt the soft way, there may have to be a one-time major confrontation to embed the teaching in the psyche of a whole generation. That is a lesson the Hindus learnt the hard way when the Khalistan movement was buried at one swoop. That is the moral many Hindus have drawn from the communal peace that has prevailed in Gujarat after the post-Godhra violence.

A positive point in Modi’s favour is the neat way he has tied up his foreign policy with the fulfilment of domestic promises. On his recent tour of Japan, not only did he persuade the Japanese to invest heavily in India, he involved them in his pet projects of bullet trains, revamping of cities, building of a new Varanasi as a blend of the ancient and the modern and even the cleaning of the Ganga.

Some of us used to feel apprehensive about Modi’s alleged dictatorial attitude. This notion was strengthened when he seemed to be fashioning the PMO as the fulcrum of his administration. Especially when he appointed his protégé, Amit Shah, as the party president.

But this negative point has been stood on its head by the positive results that the system seems to be achieving from such centralisation of authority. Decision-making has been hastened by the abolition of cabinet committees, which had ceased to be vehicles of coordination and got converted into instrumentalities of delay. A bunch of ministers and MLAs was not allowed to visit Brazil during the World Cup at State expense. A minister was seen wearing jeans at the airport and ordered to go home and first change into something more decorous. Maneka Gandhi was quietly chastised for making an uncouth bid for Varun’s political ascendancy by denying him a place in the party top brass. Bureaucrats started receiving calls on the RAX phones from the Prime Minister himself, who incidentally also ensured thereby that they remained in office for the mandated 12 hours. There was a hint administered through the grapevine that bureaucrats who played golf on week days would not be preferred.

Today, most people are saying that India voted for Modi mainly because it wanted a strong leader. So we have no business cribbing about Modi’s strong leadership. Were Lee Kuan Yew or Deng Xiao-Peng not dictators?

A very important factor in my reassessment of Modi is his tremendous sense of humour. I liked the way he played the flute and beat a drum in Japan (although Rahul, the heir apparent, did not). We all relished the replies he gave to school students on Teachers’ Day. His frankness in admitting to his childish pranks was admirable, like how he stapled the clothes of gentlemen and ladies standing close to each other in marriage parties.

He made fun of his political opponents by predicting with an impish smile that his presenting a copy of the Bhagwad Gita to the Japanese Emperor would be criticised in India as an act of promoting Hindutva. And, not surprisingly, his secular antagonists promptly fulfilled his prophecy.

TALKING of prophecies, I cannot but allude to the prediction supposedly made by Nostradamus, in which he not only foretold the rise of Modi as the leader of a country surrounded on three sides by water, but also spoke of his phenomenal emergence as a global leader presiding over the destiny of a superpower. He also talked of Hindu nationalism and the re-emergence of India as a world teacher. Other predictions include the disappearance of Pakistan and the integration of Kashmir by India. But Google also takes you to Ramani’s blog, which claims that research has proved that this news is a spoof.

Be that as it may, many of us have a feeling that Modi was not joking when he obliquely told a boy on Teachers’ Day that he (Modi) had nothing to fear till 2024. He has hinted even otherwise that he will be there for 10 years at least. In 2024, Modi will be 73, very close to his self-imposed upper age limit of 75 years for political leaders holding high office. What he will do thereafter is anybody’s guess!

MK Kaw is a former Secretary, Government of India