- Cover Story

- Governance

- Globe Scan

- Corruption

- State Scan

- Talk Time

- Cover Story

- Governance

- Globe Scan

- Corruption

- State Scan

- Talk Time

Recent Posts

© Copyright 2007 - 2023 Gfiles India. All rights reserved powered by Creative Web INC.Globe ScanChina’s Belt Road – Great opportunity for India

If India were a partner in the BRI, her potential as a power will not be easy for China to ignore; whereas by staying away from it, India would be surrendering her role as a countervailing power, not only at the BRI forum but also in the region and the world

Karan KharbApril 15, 20187 Mins read1.9k Views

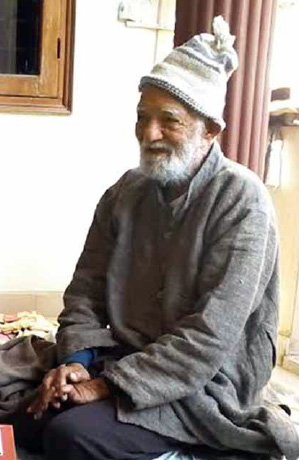

Written by Karan Kharb

Written by Karan KharbEVEN as the military stand-off between India and China at Doklam was amicably resolved on India’s terms last year, much of the media and many strategists in India have continued to express serious apprehensions about China’s growing hegemonic ambitions in the region. The recent news of the Communist Party of China (CPC) endorsing Xi Jinping’s term as President for Life has given a fillip to these apprehensions in the politico-diplomatic circles throughout the world, but more so in India. Ever since Xi came to power in 2013, he has embarked upon revamping the government machinery, including purging the military and the Party of corrupt leaders. His vision to expand China’s influence across continents and oceans became clear when he propounded the idea of ‘One Belt One Road’. The big question, however, is: How justified are India’s apprehensions!

The concept of One-Belt-One-Road (OBOR), which is now commonly called ‘Belt-Road Initiative’ (BRI), is undoubtedly a masterstroke in the geo-strategic matrices of today’s world that could significantly alter the equations among the regional and global powersThe concept of One-Belt-One-Road (OBOR), which is now commonly called ‘Belt-Road Initiative’ (BRI), is undoubtedly a masterstroke in the geo-strategic matrices of today’s world that could significantly alter the equations among the regional and global powers. At a time when China’s economy is on a decline from its high growth path, this masterstroke will expand China’s strategic and economic reach across the world. The concept seeks to connect China seamlessly with Central Asia, Europe, West Asia, Eastern Africa and the littoral States of the Indo-Pacific. The term ‘One Belt’ and ‘One Road’, respectively, signify revival of the ‘Silk Road Economic Belt’, a network of ancient trade routes that connected the East with the West linking the underdeveloped hinterland of China with Eurasia and Europe; and ‘Maritime Silk Road’, that will connect China’s southern provinces to the South East Asian markets through railways and sea lanes across Indian Ocean and West Pacific.

THE mapping of the BRI network, i.e. highways, ports and rail lines, will generate enormous commercial opportunities across 65 countries, that is, 60 per cent of the global populace controlling a third of the total economic output of the world. It will boost China’s maritime activity across the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean, connecting China’s coastline with Persian Gulf and Africa’s East coast besides SE Asia and South Asia.

Proposed ‘One Belt One Road’ project – China in red, Members of the AIIB in orange, the six corridors in black Even as most countries in India’s neighbourhood are excited about the BRI project, India has been wary about China’s grand strategy to encircle India by casting a ‘String of Pearls’ around it in the form of development packages for the economically weaker countries in the region. India’s concerns, no doubt, have reasonable grounds that make China’s intentions suspect. Firstly, the development of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which is part of the BRI project, passes through the Indian territory illegally occupied by Pakistan, and with the Gwadar port under its control it gives China easy access to the Arabian Sea. Secondly, China’s quest to dominate the Indian Ocean by luring the smaller countries in the region through its policy of ‘Charm Offensive’ that includes infrastructure development projects like ports, airports, rail-road network and oil-pipelines could well be China’s way of developing her own military bases in the region to legitimise her presence in the Indian Ocean.

Gwadar Port, already functional under the Chinese control, gives China easy access to the Arabian Sea India’s concerns, no doubt, have reasonable grounds that make China’s intentions suspect. Firstly, the development of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which is part of the BRI project, passes through the Indian territory illegally occupied by PakistanWhereas India’s apprehensions about the BRI Project have not been hidden, there are countries in the affected zones of the grand Initiative, especially in the Eastern Europe, SE Asia and even in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR), that have welcomed the idea. As many as 52 sovereign countries are today on board with China on BRI. Significantly, even Russia has exhorted India to join the project. This eloquent and mammoth support makes BRI a reality of the future, India’s reservations notwithstanding. The CPEC project, India’s most vexatious concern in this gamut, is nearing completion with the Gwadar Port already functional under the Chinese control. Several infrastructure development projects like ports, airports and rail-road networks have been either accomplished or are currently in progress in Myanmar, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Maldives.

As a counter to BRI, India and Japan have jointly enunciated a plan called ‘Asia-Africa Growth Corridor’ (AAGC). While the BRI idea encompasses both land and oceanic routes, AAGC is essentially a network of sea lanes connecting India with Africa and the countries of SE Asia and Oceania. While China is developing Pakistan’s Gwadar port, India is developing Iran’s Chabahar port that will give access to Afghanistan, Central Asian countries and several European countries aspiring to connect with the Gulf bypassing Pakistan. India has ignored China’s warnings and steadfastly continued to support Vietnam in its oil exploration activities in the South China Sea. Likewise, it has been undertaking developmental projects in a few other ASEAN countries as well as SAARC members.

Last year, on the side-lines of the ASEAN summit in Manila, India, Japan, Australia and the US met to lend support to Shinzo Abe’s 2007 idea of ensuring “a free, open, prosperous and inclusive Indo-Pacific region.” Although, the ‘QUAD’, as the initiative is called today, is a non-formal association, it has found ‘silent’ support among the ASEAN countries as a soft-counter force to check China’s dominance in the region, especially in the aftermath of her audacious advances into the central South China Sea. Even more significantly, India’s partnership in this dialogue highlights how India’s ‘Act East’ policy has fructified in enhancing her status in the Asian and trans-Asian geopolitics. The region that was “Asia-Pacific” is now being called “Indo-Pacific” by the western world, which also highlights India’s countervailing potential signalling that China is not the only power in the region.

In addition, India has also launched its soft-power initiatives to connect nations in the region. ‘Project Mausam’, a Ministry of Culture project, seeks to rejuvenate relations with countries of the Indian Ocean by enhancing cultural exchange. Besides developing Iran’s Chabahar port, India is also developing naval ports in countries of the IOR like Madagascar, Seychelles, and Mauritius.

LONG before Xi Jinping’s idea of OBOR, India, Russia and Iran had conceptualised and initiated a similar project—the International North–South Transport Corridor (INSTC), a 7,200-km long multi-mode network of ship, rail, and road route connecting India, Iran, Afghanistan, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Russia, Central Asia and Europe.

As many as 52 sovereign countries are today on board with China on BRI. Significantly, even Russia has exhorted India to join the project. This eloquent and mammoth support makes BRI a reality of the future, India’s reservations notwithstandingThe focus of the modern world is shifting from ‘geo-politics’ to ‘geo-economics’ today. Both China and India have emerged as giants in economic growth in the post-2008 economic crisis world. India’s apprehensions of China’s hegemonic ambitions seem to be based more on apparitions of the forgettable past than on substance of concrete evidence. Sporadic cases of intrusion and tussle between the Indian and Chinese troops notwithstanding, not a bullet has been fired anywhere on the 4,056 km Line of Actual Control (LAC) since the Nathu La episode of 1967. The ‘all-weather friendship’ between China and Pakistan might irk India, but they are both sovereign nations and perhaps pushed into this relationship by their shared animosity towards India. This can change. In 2016-17, India’s bilateral trade with China was $71.48 billion, recording a marginal decrease in India’s trade deficit. Besides the 12 investment agreements aggregating to $20 billion signed during President Xi Jinping’s visit to India in September 2014, as many as 600 Chinese companies have offered to invest a total of about $85 billion in India in projects that will create an estimated 7,00,000 jobs in the country in next five years.

Lot of water has flown down the Brahmaputra in the post-1962 era. Crying need of the time is rapprochement between the two nations paving way for enhanced cooperation in commerce and other areas of mutual interest.

India and China being the key players on this hemisphere of the globe, their geo-strategic interests will continue to pass through conflicts from time to time. India therefore needs to build up her own power and clout to check China from overwhelming India’s influence in the region. Some projects like the CPEC may be disadvantageous to India, but there are also some very significant advantages for India if she opts to join the BRI. A paradigm shift in India’s strategic positioning is needed to see those advantages clearly. Firstly, of the 65 countries affected by BRI, 52, including India’s neighbours except Bhutan, are already on board with China. There is no way India can stop it. By staying out of the project, India is risking its own isolation, tempting her allies to flee. Secondly, there are grounds for India to work out a win-win situation by tweaking its countervailing potential to a partnership with China in the pursuit of mutual interests while guarding her own in the IOR and the Indo-Pacific. Thirdly, the key to BRI’s success lies in factors like regional transport, energy security and blue economy.

India and China being the key players on this hemisphere of the globe, their geo-strategic interests will continue to pass through conflicts from time to time. India therefore needs to build up her own power and clout to check China from overwhelming India’s influence in the region. Some projects like the CPEC may be disadvantageous to India, but there are also some very significant advantages for India if she opts to join the BRI. A paradigm shift in India’s strategic positioning is needed to see those advantages clearly. Firstly, of the 65 countries affected by BRI, 52, including India’s neighbours except Bhutan, are already on board with China. There is no way India can stop it. By staying out of the project, India is risking its own isolation, tempting her allies to flee. Secondly, there are grounds for India to work out a win-win situation by tweaking its countervailing potential to a partnership with China in the pursuit of mutual interests while guarding her own in the IOR and the Indo-Pacific. Thirdly, the key to BRI’s success lies in factors like regional transport, energy security and blue economy.India’s geography makes her position strategically most vital in the security of sea traffic in its East, South and West. By joining BRI, India will naturally enhance her own importance here. Fourthly, China has surplus capital and cheaper technology to accelerate development and, like other nations, India also needs funds and resources for its own development projects. Fifthly, BRI will throw open new trade connections for India with many countries. Sixthly, India is already a member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO). As a BRI partner, she will find it only easier to make forays into Central Asia besides acquiring an influential role within SCO too.

If India were a partner in the BRI, her potential as a power will not be easy for China to ignore; whereas by staying away from it, India would be surrendering her role as a countervailing power, not only at the BRI forum but also in the region and the world. India’s policy makers must remember that in the ancient times too, it was along the ‘Silk Route’ along which India’s trade flourished and her philosophy and Buddhism spread across Asia and beyond.

Recent Posts

Related Articles

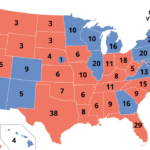

Globe ScanThe US Elections 2024: small number of voters in a few key states will decide the fate of Biden and Trump

Written by Gfiles Editor By Ashe N Ayers If you don’t know US...

ByGfiles EditorJuly 21, 2024Globe ScanFive billion passengers and earning is $6.14 per passenger claims Willie Walsh, Director General IATA

Written by Special Correspondent Willie Walsh Director General IATA presented a report at...

BySpecial CorrespondentJune 3, 2024Globe ScanIs Netanyahu, PM Israel, under pressure to resign?

Written by Gfiles Editor Iran’s unprecedented attack on Israel on April 14, in...

ByGfiles EditorMay 13, 2024Globe ScanThe bear flexes muscle

Written by Nivedita Kapoor IN 2016, Russian President Vladimir Putin announced the project...

ByNivedita KapoorMay 5, 2020 - Governance

- Governance

India and China being the key players on this hemisphere of the globe, their geo-strategic interests will continue to pass through conflicts from time to time. India therefore needs to build up her own power and clout to check China from overwhelming India’s influence in the region. Some projects like the CPEC may be disadvantageous to India, but there are also some very significant advantages for India if she opts to join the BRI. A paradigm shift in India’s strategic positioning is needed to see those advantages clearly. Firstly, of the 65 countries affected by BRI, 52, including India’s neighbours except Bhutan, are already on board with China. There is no way India can stop it. By staying out of the project, India is risking its own isolation, tempting her allies to flee. Secondly, there are grounds for India to work out a win-win situation by tweaking its countervailing potential to a partnership with China in the pursuit of mutual interests while guarding her own in the IOR and the Indo-Pacific. Thirdly, the key to BRI’s success lies in factors like regional transport, energy security and blue economy.

India and China being the key players on this hemisphere of the globe, their geo-strategic interests will continue to pass through conflicts from time to time. India therefore needs to build up her own power and clout to check China from overwhelming India’s influence in the region. Some projects like the CPEC may be disadvantageous to India, but there are also some very significant advantages for India if she opts to join the BRI. A paradigm shift in India’s strategic positioning is needed to see those advantages clearly. Firstly, of the 65 countries affected by BRI, 52, including India’s neighbours except Bhutan, are already on board with China. There is no way India can stop it. By staying out of the project, India is risking its own isolation, tempting her allies to flee. Secondly, there are grounds for India to work out a win-win situation by tweaking its countervailing potential to a partnership with China in the pursuit of mutual interests while guarding her own in the IOR and the Indo-Pacific. Thirdly, the key to BRI’s success lies in factors like regional transport, energy security and blue economy.